The Life, Legend and Lessons of Martin Lomasney: Ward Boss & West End Icon

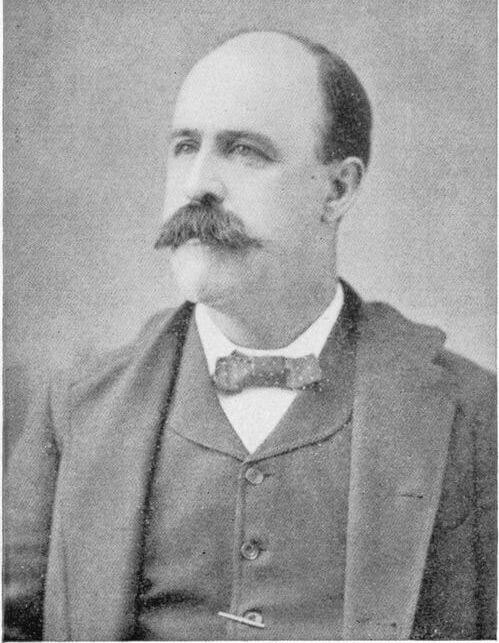

From the late 1800s well into the first half of the 20th century, Boston’s political landscape was combative at best, and corrupt at worst. Such was the arena a young Martin Lomasney entered when he first stepped onto the City’s political stage at the tender age of 16. But far from falling victim to this lion’s den, Lomasney endured and went on to wield substantial political power, primarily as a ward boss.

Today, there is no real equivalent to the old ward bosses, even though some politicians have played a similar role on occasion and some non-elected/non-appointed individuals do exert significant political clout. In Lomasney’s day, everyone knew their ward boss and, largely, either revered or loathed him. Lomasney certainly had his detractors, but most of his constituents, including residents of the Old West End, held him in high regard.

“Martin Lomasney is without a doubt one of the central figures in West End lore,” says Duane Lucia, executive director of the West End Museum. “His influence on the community, both socially and politically, cannot be overstated. To this day, the street named after him (Lomasney Way) is a testament to the legendary status he holds with many current and former residents of the area.”

Born in Boston in 1859, Lomasney was the son of Irish immigrants who fled to the U.S. during the great potato famine. His parents and two of his siblings died when he was still a child, forcing Martin and his brother Joe to move in with an aunt. After leaving school in the eighth grade, Lomasney befriended a local ward boss, who steered him from trouble and gave him a job as a lamplighter and health inspector. In 1875 he entered politics as an aide to Boston’s Democratic boss, Michael Wells.

Within 10 years, Lomasney had become entrenched as the indisputable boss of Ward 8 (later Ward 5, then Ward 3), which encompassed the West End. He and Joe soon founded the Hendricks Club at the corner of Lowell and Causeway streets. The establishment began as a social club, where neighborhood men would gather simply to enjoy each other’s company. But, with no existing social welfare net, the Hendricks Club also became the place that members of the community turned to for shelter, food and help finding work. Ultimately it became the heart of Lomasney’s political machine, with a primary function of rallying and organizing of voters.

The ward bosses of Lomasney’s era were widely known for grafting and voter fraud, and while Lomasney was no angel, he earned a reputation as a man of great intelligence and integrity throughout his political career. He did partake in the pervasive “mattress voter” campaigns of the day, bringing in homeless men to temporarily stay in ward residences during the annual April 15th voter counts. But when it came to corruption in such matters as city infrastructure contracts, Lomasney openly fought against it, sometimes at great personal risk. In 1920, he discovered that a contractor was bilking the city and successfully got that contractor fired. Subsequently, the contractor showed up at City Hall, pulled a gun and shot Lomasney. While recovering at the hospital, Lomasney said, with his typical wit, “People might not like their Aldermen, but they don’t think we should be shot without a fair trial.”

When Lincoln Steffens, a New York journalist known for investigating corruption in municipal government, came to Boston to spend time with Lomasney, he found a man who was an exception to the rule. Steffens said Lomasney was probably the best public servant he had ever met, that he was scrupulously honest and wholly committed to his constituents. Historian Doris Kearns Goodwin wrote of Lomasney, “He lived a simple, low-key life, renting a small apartment and wearing the same old battered straw hat year round, but to the people of the West End he was a god. Arriving early each morning at his headquarters, Lomasney worked 365 days a year, caring for ‘his’ people in all phases of their lives.”

A lifelong bachelor, Lomasney dedicated his life to building his political machine through a base of unwaveringly loyal aides and constituents. According Suffolk University History Professor Robert Allison, “Lomasney would walk the city every night, often greeting immigrants as they arrived on Boston’s docks. He was very bright and invested a lot in real estate. In fact, he’s responsible for the Boston Garden being built.”

He was a man of few words, unless a particular occasion, like a highly contested election, required more. Lomasney’s best known quote exemplifies his affinity for pithiness as well as his advice to fellow politicians, “Never write if you can speak; never speak if you can nod; never nod if you can wink.” (Also attributed to Lomasney in abbreviated form as “Don’t write when you can talk; don’t talk when you can nod your head.”)

Lomasney was undeniably steadfast, tough and fervent, all of which made him a remarkably effective political organizer. On the eve of an election, he would bring together his constituents at the Hendricks Club and tell them who to vote for. Often, his urgings grew quite animated, with Lomasney taking off his jacket, then tie, then collar as he got more and more agitated in his bid to persuade residents to vote one way or another. Lomasney always maintained that his reasons for pushing a particular candidate or derailing another were strictly based on the best interests of the ward.

Despite his unquestionable political power and position, Lomasney hated being called a ward boss. He repeatedly downplayed this title, once saying, “A boss gives orders. I don’t. When I want something done I ask for it. Just before the election we send out suggestions to the voters. We don’t tell ‘em how to vote. We just suggest.” He equally dismissed the moniker of “czar,” which journalists applied to him. On one occasion when Lomasney refuted the ward boss term, a reporter asked, “What about mahatma?” Understanding that mahatma indicated more of a spiritual leader, Lomasney agreed that term would be acceptable.

Historians point to additional ways that Lomasney distinguished himself from the other Irish ward bosses of his era like Patrick Joseph “P.J.” Kennedy, “Smiling Jim” Donovan, James Michael Curley and John Francis “Honey Fitz” Fitzgerald. Many of the Irish bosses were slow to embrace constituents of other ethnic and racial backgrounds. But, as long as they registered to vote, Lomasney treated all residents of his ward the same. When it came to recommending constituents for city and state jobs, which all of the bosses did, Lomasney would just as easily recommend someone of Irish descent as he would someone of another ethnicity or race. As long as a resident was relatively fit for a job, Lomasney would recommend him and even try to get him there first, ahead of the other ward bosses’ applicants.

At different points in his political career, Lomasney served as Alderman, State Representative and State Senator, but he preferred not to serve in formal office. The ward boss position was informal; no one was officially elected or appointed to this role. “You became ward boss by being ward boss,” says Allison. In reality, the ward bosses of the day had more political influence than those in elected office because of the personal relationships they cultivated with voters, helping them find jobs, housing and the like. These relationships translated to a stranglehold on elections, with the ward bosses essentially able to dictate their constituents’ votes. For Lomasney’s part, over the course of nearly 50 years, no political candidate from his district ran a successful campaign without his endorsement.

But Lomasney’s legacy is about far more than political prowess. He stood for community—banding together for the common good and taking care of one another. Today, as new apartments are drawing more residents to the West End, Allison says there are vital lessons to be learned from Lomasney’s example. “He pulled seemingly disparate people—Irish, Italian, Jewish, African American—together. He showed that a neighborhood can be built and a true sense of community instilled even in apparently difficult circumstances.”

As the West End continues to grow, its rich history should be honored and celebrated, all the while creating and fostering a renewed appreciation of community cohesion and identity. That’s how Boston’s mahatma would want it.