Warrior for Women’s Justice in the West End: Arianna Sparrow

Throughout America’s history, our search for a more just society has often progressed through activism and reform. People challenge the status quo for the sake of social justice to improve the republic. Those improvements often take the forms of new and amended laws or transformed perceptions of the people around us. Today is no different. Many still endeavor to preserve and expand civil liberties to position America as a more inclusive nation. That’s why this Black History Month, we’re profiling a woman who made her difference crusading for the rights of women and African-Americans in late 19th century Boston.

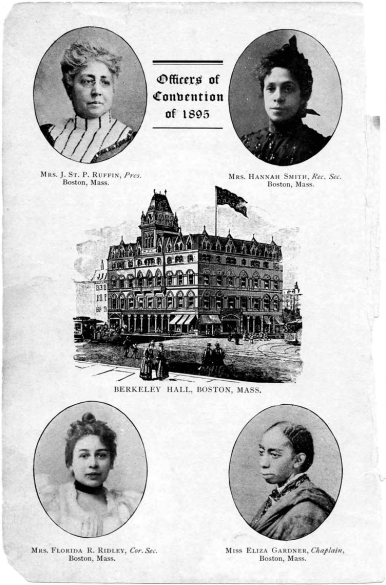

Arianna Sparrow was a noted contributor to the suffrage movement in the Beacon Hill community starting in the late 1880s. She helped spearhead awareness initiatives alongside other women of color and leading suffragists in the Beacon Hill community, such as Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Maria Baldwin.

She first moved to Boston with her mother in 1852. Years later, she co-founded two distinct groups that advocated for suffrage causes as well as civil rights for people of color – the West End Woman Suffrage League and the Woman’s Era Club. After helping start the suffrage league in 1887, Sparrow served as an executive committee member. The group’s meetings often took place at the Twelfth Baptist Church on Phillips Street where they coordinated several activities in and around the West End, which was home to a large African-American population during the time. Sparrow’s home was also used as the main space for league members to visit and read the Woman’s Journal, a suffragist publication where the league reported details of their meetings and updates on their activities.

In 1893, after years of working on women’s reform efforts, Sparrow co-founded the Woman’s Era Club—an organization devoted to serving the interests and civic aims of Black people. The club was the first of its kind in Boston and was formed “for colored women and by colored women, to the end that problems of vital interest to the colored population might be discussed.” Club founders wrote and published the first national newspaper ever to be founded and edited by Black women called The Woman’s Era. Members raised money to purchase scholarships for African-American children to attend schools. They also led classes discussing “civics, domestic science, literature, public improvements, and questions of public importance to the colored race.” Additional fundraising efforts aided rights initiatives by people of color in Boston and other cities.

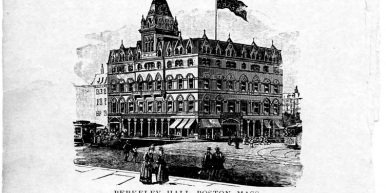

The emergence of Black women’s clubs across the country even led to the birth of the First National Conference of Colored Women of America hosted in South Boston in 1895, which Sparrow helped arrange.

Not only was Sparrow a respected community activist in the West End, she was also a soprano singer. She was a longtime member of the Handel and Haydn Society, an internationally acclaimed performing arts group in Boston and sang at churches around the Beacon Hill community. She also performed a solo at the 1895 National Conference of Colored Women. Impressively enough, her skills didn’t wane with age. Due to what pianist and civil rights activist Maud Cuney-Hare called “excellent training” in her book Negro Musicians and their Music, Sparrow was able to maintain “the natural sweetness of her voice and purity of tone that enabled her to sing acceptably in St. Augustine Episcopal Church (Boston) when over eighty years of age.”