Topic: Neighborhood Life

Street corner society, urban villagers, peer group society, life in the immigrant era

Hyman Bloom is remembered as a key figure from the Boston Expressionist movement, praised for his mystical and vibrant paintings. Bloom, in addition to being a visionary artist, offers us a window into Boston’s settlement houses in the 1920s and ‘30s. The West End Community Center, and its artist-teacher Harold Zimmerman, nurtured the creativity of a generation of future artists, from Bloom to Jack Levine.

St. Joseph’s Church was established in 1862 on Chambers Street in the West End, near the site of the first public Catholic mass in Boston. In the early 1900s, the St. Joseph’s Association, an organization of parishioners, hosted an annual party at the church which also held many notable funerals, marriages, and worship services. Decades after urban renewal, West Enders reunited at annual masses at St. Joseph’s to honor deceased fellow residents.

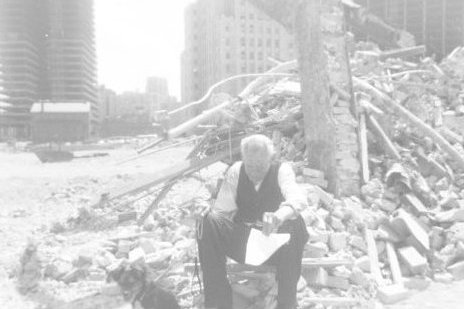

Urban renewal projects, like that in the the West End, have long promised to revitalize aging urban areas, create economic opportunities, and improve living conditions for residents. Despite these positive intentions, urban renewal has also resulted in false promises, the physical destruction of neighborhoods, and forced removal of residents. Such negative impacts have resulted in social isolation, lost social connections, and loneliness.

Boarding Houses played an important role in the housing system during the age of industrialization and immigration in Boston and the West End. Along with lodging and rooming houses, they were the only alternative for those in need of affordable and transitional living space in the neighborhood until the arrival of tenements and apartment buildings. Boarding houses also offered women of the period one of the few ways to earn a decent income.

The Old West Church, standing at 131 Cambridge St, is one of the few surviving buildings of the historic West End. Since its opening in 1806, the building has served as a church, a library, a shelter, and a church again. It continues to hold masses and contribute to the Boston community today.

Hundreds of boys from the West End and other parts of Boston benefited from the financial, education, and moral support provided by the Burroughs Newsboys Foundation.

Richie Nedd was one of the historic West End’s Black residents and a board member of The West End Museum before his passing in 2011. Nedd’s article for the June 1998 issue of The West Ender, “A Black Man’s View of the West End,” features he and other Black residents coming together in reunions of hundreds of West Enders after urban renewal.

The first of three homes built for politician and land developer Harrison Gray Otis by architect Charles Bulfinch still stands proudly today as one of the only surviving buildings of the West End’s urban renewal.