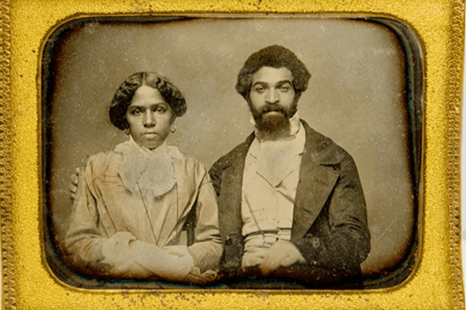

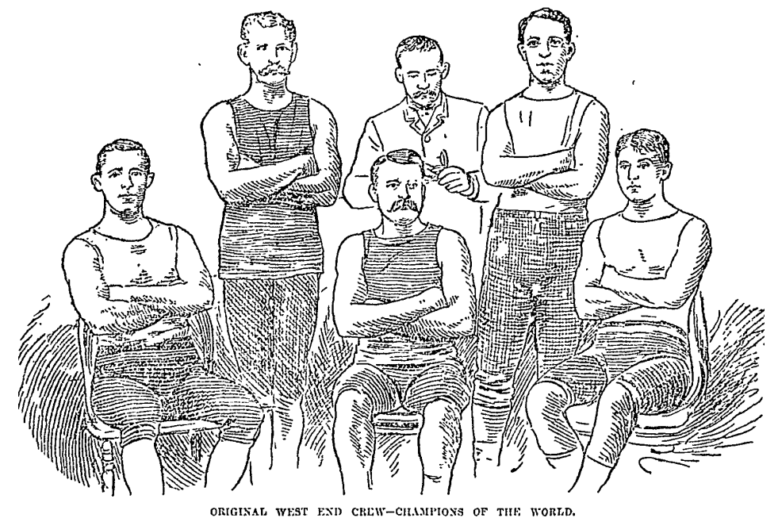

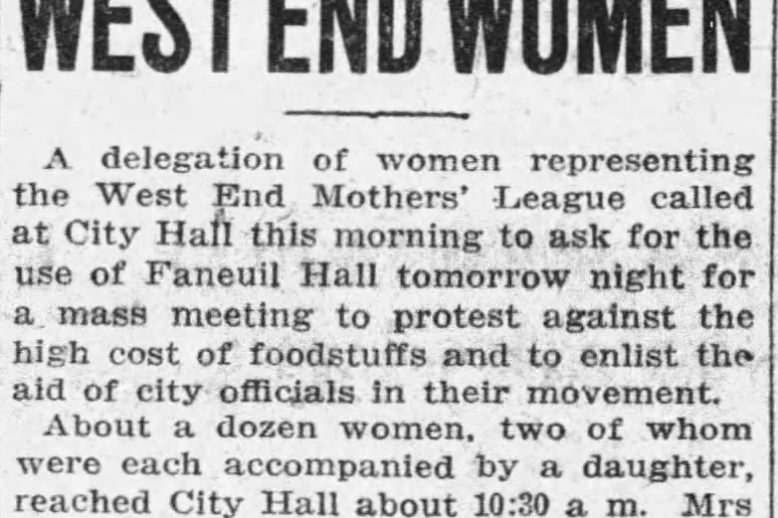

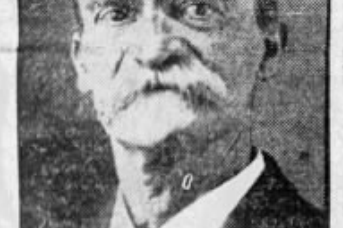

Ray Reddick’s African-American Ancestors in Boston’s Historic West End

Raymond Reddick, a lifelong Boston resident who is now 74 years old, has spent decades collecting, documenting, and speaking to different audiences about his extensive African-American family history with deep ties to the historic West End.