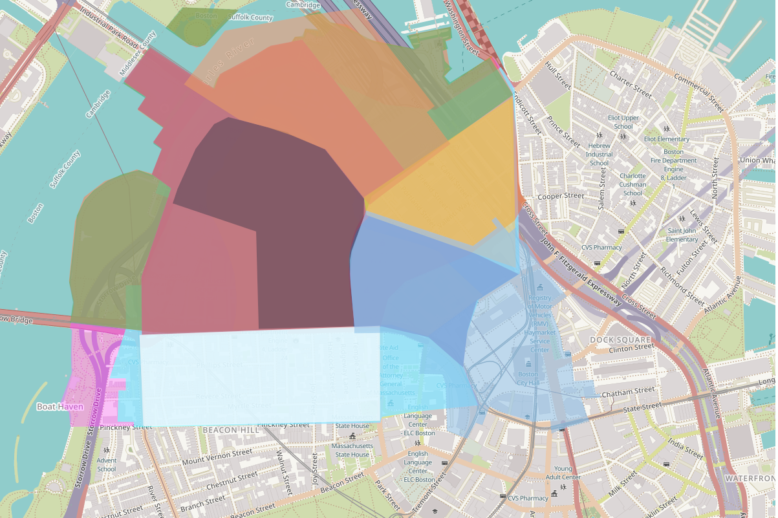

Italians and Eastern Europeans, mainly Jews, make up most of the West End’s population of 18,442* in 1920, supplanting the former majority of Irish and Eastern European Jews, who from 1895 onwards had begun their diaspora to Dorchester, Roxbury, and the suburbs. From this time forward, the West End’s population will only decrease, the effect of the Great Depression, World War II, and second generation Americans leaving to seek middle-class living in different neighborhoods of Boston or the suburbs, leading to a decrease in overpopulation and “de-slumming”**. The City of Boston’s announcement in 1951 that much of the West End neighborhood will be demolished as part of an urban renewal plan inspires further migration until only 2,700 families remain in the Spring of 1958.

*U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1920 **Death and Life of Great American Cities, Jane Jacobs