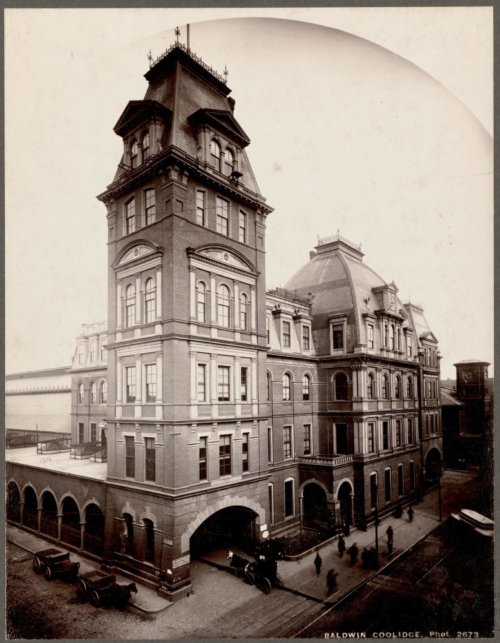

Urban Renewal in Boston’s Charlestown Neighborhood and Lessons Learned from the West End

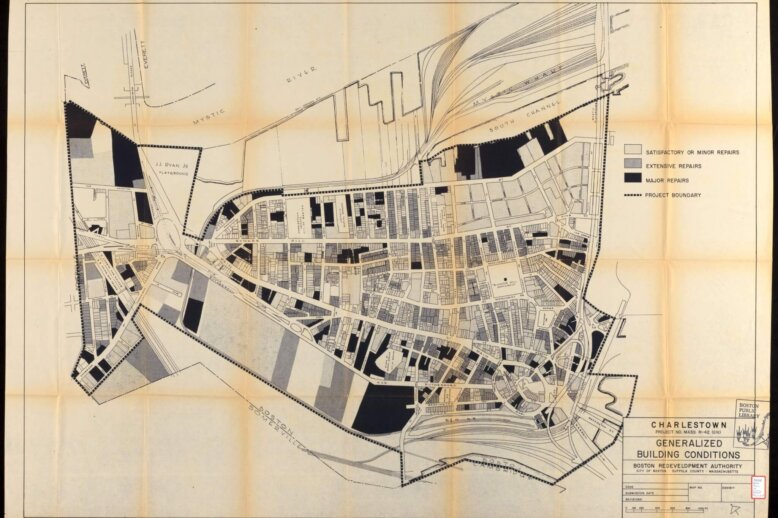

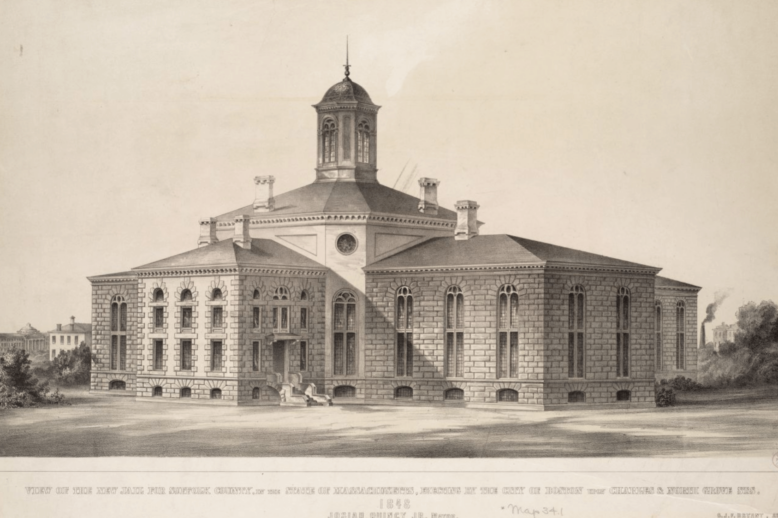

Boston’s urban landscape has been dramatically shaped by urban renewal initiatives of the mid-20th century. Among the most notable examples are the West End and Charlestown—two historic neighborhoods with starkly divergent urban renewal results. While the West End became the poster child for urban renewal’s destructive potential, Charlestown had a very different outcome only a few years later. This article examines these contrasting urban renewal experiences, highlighting their implementation approaches, community responses, and lasting impacts on Boston’s urban fabric.