Affordable Housing in the West End: Initial Plans and Current Realities

The story of urban renewal in the West End is a complex one, marked by both ambitious plans and challenging realities when it comes to affordable housing. Over the past seventy years, the West End has served as a cautionary tale, full of broken promises and ongoing struggles for income-restricted housing. More recent efforts, such as the affordable housing initiative that is part of the redevelopment of the West End branch of the Boston Public Library, look to address this past.

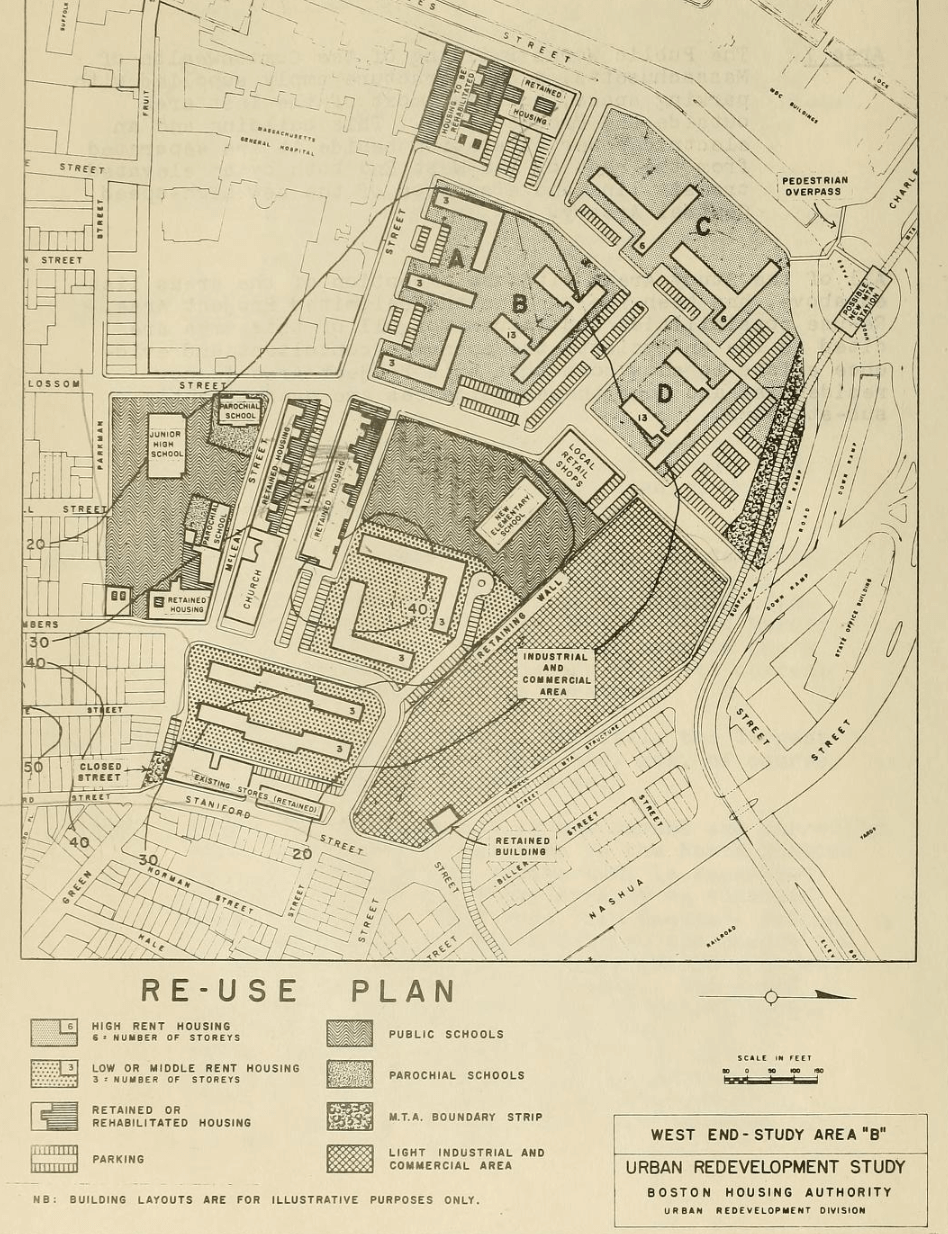

In 1953, the Boston Housing Authority unveiled a redevelopment plan for the West End that promised a balanced approach to housing in the neighborhood. The Plan outlined that, out of the proposed 17.6 acres of residential area, 4.8 acres (27%) would be designated for “low-rent public housing or middle-income private housing.” Additionally, the Plan aimed to preserve or rehabilitate 57 structures with 375 residential units across 2.6 acres (15%). And finally, 58% of the residential area was designated as “high rent private housing,” reflecting the higher land values in a coveted soon-to-be-new neighborhood near downtown Boston.

Several revisions to the original redevelopment plan were presented through 1959, further adjusting the boundaries and land uses of the proposed project area to eventually lay the foundations for the new West End we know today. In the May 1957 revision, the total project acreage grew from the 1953-proposed 37 acres to nearly 48 acres. Significantly, it was also recommended that the future residential area, which expanded from 17.6 to more than 27 acres, would be developed by one private developer. The 1957 document argues: “Because of the local objectives to be achieved and the operational problems involved, it would be highly impractical to dispose of the land to more than one redeveloper… The best method of redevelopment dictates disposition to one redeveloper.”

It further explains that the “large size of this redevelopment project (2400 dwelling units) involving approximately thirty million dollars construction costs, means that the redeveloper must make a considerable investment, assume more than ordinary risk and must possess extensive experience in similar large-scale operation.” This revision highlighted three local objectives that were “desired to be attained by the redevelopment,” the first of which was “middle-income housing at rentals consistent with prevailing construction costs,” but failed to mention measures by which to advance the building of income-restricted housing. Ultimately, in the first 15 years post-demolition, the only residential buildings that had been built in the West End were six new luxury high-rises.

The 1990s brought hope with the Lowell Square project, later known as West End Place, which was meant to provide meaningful opportunities for displaced residents. Yet, the project fell short, with only a limited allocation of low-income units that community leaders found insufficient.

Today, the affordable housing landscape in the West End paints a more balanced picture. On the one hand, some developments have a significant portion of affordable housing. For example, 100% of The Blackstone Apartments’ 145 total project units are income-restricted; similarly, 100% of The Beverly’s 239 units are income-restricted; and 80% of the Amy Lowell Apartments’ 152 units are income-restricted. However, the most recently completed projects, Alcott Apartments (35 Lomasney Way) and The Sudbury (100 New Sudbury Street), contain a much smaller percentage of affordable housing – 7% and 13%, respectively, with a total of 97 income-restricted units.

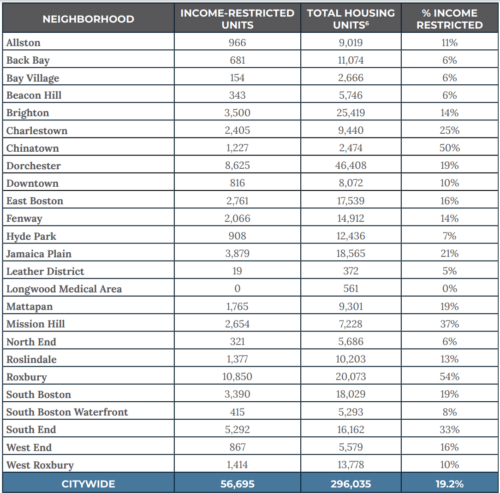

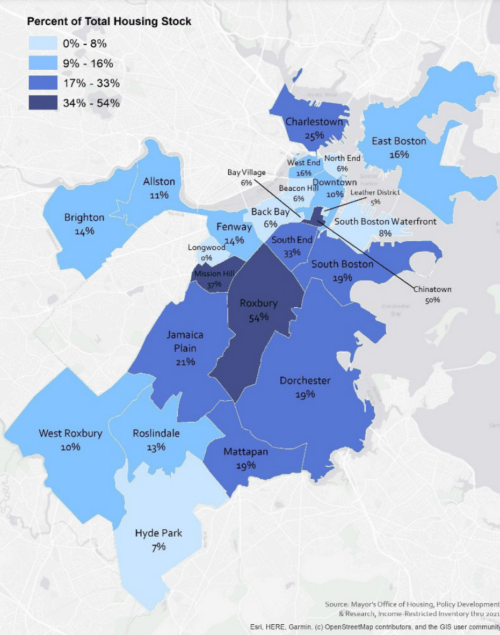

Overall, the data suggests that while the West End has some projects with a high percentage of affordable housing, the neighborhood still faces challenges in terms of overall housing equity. According to a City of Boston 2021 report, only 16% of its roughly 5,600 housing units are income-restricted compared to the citywide average of 19.2%. Additionally, 83% of housing in the West End is rental, significantly higher than the city’s 67% average, and only 1% of owner units are income-restricted, compared to 3% citywide. These statistics underscore the persistent challenges faced by the West End in achieving housing equity and community stability.

One of the most recent efforts to address these issues is the affordable housing initiative centered on the West End branch of the Boston Public Library. This collaborative development project, set to break ground in 2026 and be completed in 2027, promises 119 income-restricted housing units alongside a new two-story library. This initiative represents a tentative acknowledgment of past failures and a commitment to more inclusive urban development.

As Boston continues to evolve, the West End stands as a powerful reminder of the need for a more empathetic, community-centered approach to urban development. The neighborhood’s history challenges us to consider who truly benefits from such efforts and at what price. It calls for a genuine commitment to housing justice, one that prioritizes preservation over displacement and people over profit.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Boston Housing Authority, West End Project Report – A Preliminary Redevelopment Study of the West End in Boston (1953); Boston Redevelopment Authority, West End Redevelopment Plan – Revised May 1957; City of Boston, Income Restricted Housing in Boston, 2021; City of Boston, West End Library (Housing with Public Assets); Edward J. Ford Jr., Benefit-cost Analysis and Urban Renewal in the West End of Boston (1974); Adam Tomasi, “West End Place,” The West End Museum; The West Ender, “Betrayed – Again,” June, 1995 (The West End Museum Archives).