Samuel and George Parkman: A Powerful West End Real Estate Family

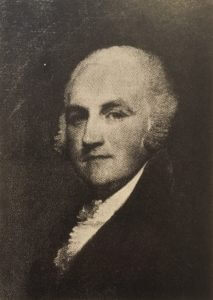

Samuel Parkman (1751-1824) and George Parkman (1790-1849) both left an enduring mark on the West End. Samuel was a Bowdoin Square real estate magnate and Charles Bulfinch patron. Like his father, George also worked in real estate, and used his fortune to donate land on North Grove Street for the site of Harvard Medical College – the building he would later be murdered in.

During the post-Revolutionary War period, Samuel Parkman built his fortune as a China trade merchant and real estate magnate. He acquired large parcels of land in the West End of Boston, including what was the strategically-located Mill Pond. In 1804, he became a partner in the land company of Parkman, Ohio & Parkman, Maine. Each partner owned 40,000 acres in Maine. Today, there are two towns named for Parkman: Parkman, Ohio and Parkman, Maine.

In 1789, Parkman built an early federal style mansion in the exclusive Bowdoin Square area in the West End. In 1816, he hired architect Charles Bulfinch to design two new attached granite houses for him and his daughter, Sarah. Civically minded, Parkman commissioned Gilbert Stuart to paint a full-length portrait of George Washington in Dorchester Heights which he gifted to the City of Boston in 1806. It hung for many years at Faneuil Hall and is now housed at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. In 1801, Parkman engaged Paul Revere to cast a bronze bell for the church of his father, the Reverend Ebenezar Parkman, in Westborough, MA. The bell was moved to Old South Church, Boston in 2011.

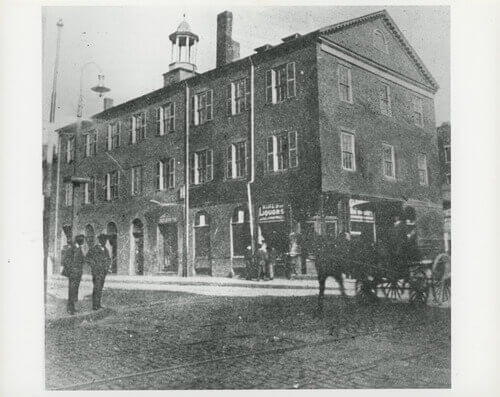

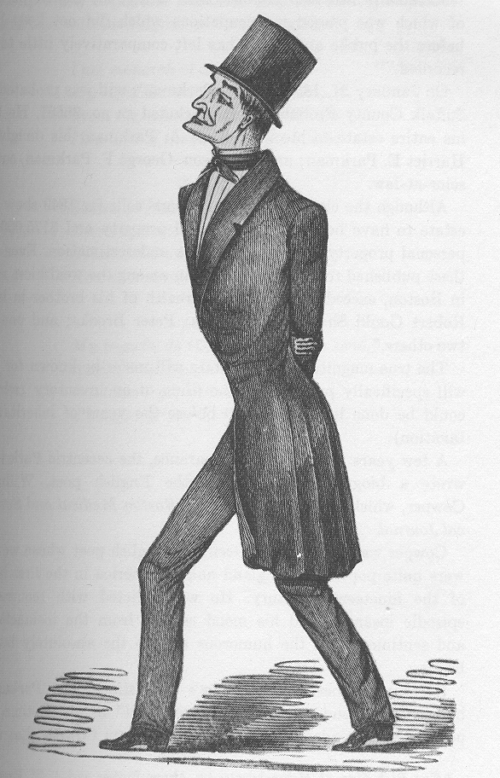

Among Samuel Parkman’s heirs was his son, Dr. George Parkman, who was born in the West End. An 1813 graduate of Harvard Medical School, George donated land on the West End’s North Grove Street for the site of Harvard Medical College and funds for the Massachusetts General Hospital building. Like his father Samuel, George Parkman increased his inheritance with real estate holdings. While Parkman could be charming with Harvard colleagues and Beacon Hill elites, in financial matters he was reputedly a “shrewd, tightfisted, cold, and calculating landlord and money lender.”

His medical school colleague, Dr. John White Webster, saw the ugly side of Parkman when he fell behind repaying money Parkman lent him between 1842 and 1848. Throughout 1849, Parkman harassed Webster in public, in private, and by mail. On Friday, November 3, 1849, Parkman confronted Webster, accused him of fraud, and threatened to have him removed from the faculty of Harvard Medical School. Desperate to prevent exposure and disgrace, Webster murdered Parkman in his laboratory at Harvard Medical School – on land Parkman himself had donated. He then dismembered the body, and threw pieces into the furnace. If not for the sleuthing of Medical School janitor Ephraim Littlefield, the case might never have been solved. Several days after the murder, Littlefield broke through the wall of Webster’s privy to discover two human femurs, a pelvis with flesh still attached, and a set of false teeth. On March 30, 1850, Webster was found guilty of first-degree murder; on August 30, he was hanged in the courtyard of the Leverett Street Jail. Though the Parkman-Webster murder trial attracted over 60,000 visitors to the court, it is remembered most by legal scholars as being the first time dental evidence was used in an American court case.

Article by Nancy Dennis, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: O.T. Bailey, “Brahma, Parkman and Webster. Murder in Medical Boston.” JAMA 220 (1972): 70–74; Joel Best, “Murder at Harvard,” The Journal of American History 91, no. 3 (2004): 1125–27; Albert O. Borowitz, “The Janitor’s Story: An Ethical Dilemma in the Harvard Murder Case.” American Bar Association Journal 66 (1980): 1540; Arden G. Christen and Joan A. Christen, “The 1850 Webster/Parkman Trial: Dr. Keep’s Forensic Evidence,” Journal of the History of Dentistry 51 (2003): 5–12; Paul Collins, Blood & Ivy: The 1849 Murder that Scandalized Harvard (New York: Norton, 2018); Kurt DiCamillo, “The Parkman House,” Vita Brevis Blog, NEHGS Collections; Craig Lambert, “Murder on Foot,” Humanities 24 (2010): 24–43.