The Fugitive Slave Church: The Twelfth Baptist Church, Leonard Grimes, and Abolitionism in the West End

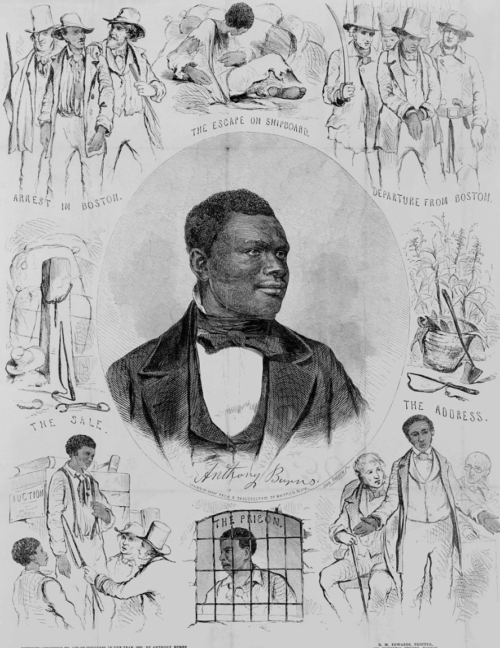

Established in 1840, Boston’s Twelfth Baptist Church was located on the North Slope of Beacon Hill (in the historic West End) until its move to Roxbury in 1906. In the 1850s and ‘60s, the Church defiantly mobilized in response to the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. Under the leadership of Leonard Grimes, the congregation raised funds to aid freedom seekers and became known as the “Fugitive Slave Church.” This active political, cultural, and religious meeting place had many prominent members and visitors from the Black abolitionist community, including Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Lewis and Harriet Hayden, Shadrach Minkins, Anthony Burns, Thomas Sims, Christiana Carteaux and Edward Mitchell Bannister, and Peter Randolph.

Between 1805 and 1840, Boston’s Black community established five churches on the north slope of Beacon Hill, most of them in the historic West End. Before the 1800s, Black Bostonians had worshipped at White churches, but were often confronted with discrimination – including segregated pews and exclusion from leadership positions. These new churches for Black congregations were not only vital spiritual centers, but important political and social gathering spaces for Boston’s Black community.

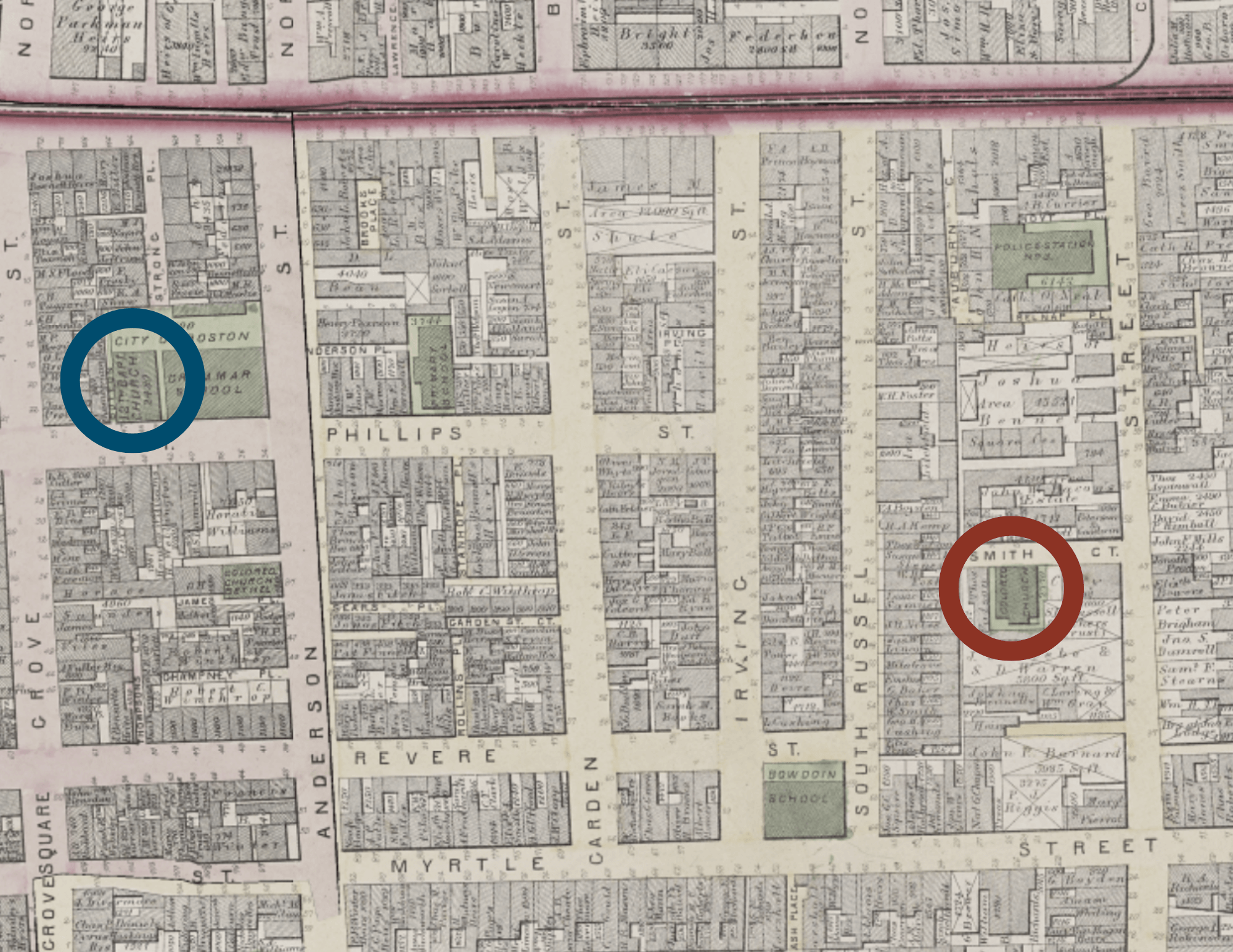

Among the most influential of these political-religious sites was the Twelfth Baptist Church, also known as the “Fugitive Slave Church” or “Second African Meeting House.” The church formed in 1840, when 46 people left the First African Baptist Church (African Meeting House) after a dispute. They secured a place in Smith Court, off of Belknap (Joy) Street, under the leadership of Reverend George H. Black. Upon his death in 1843, the small group struggled, leaderless, for a few years. By 1848, however, “it was whispered in the community that a very intelligent and useful man, by the name of ‘Grimes,’ of New Bedford, could be retained as their leader” (as reported by church historian and reverend, George Washington Williams).

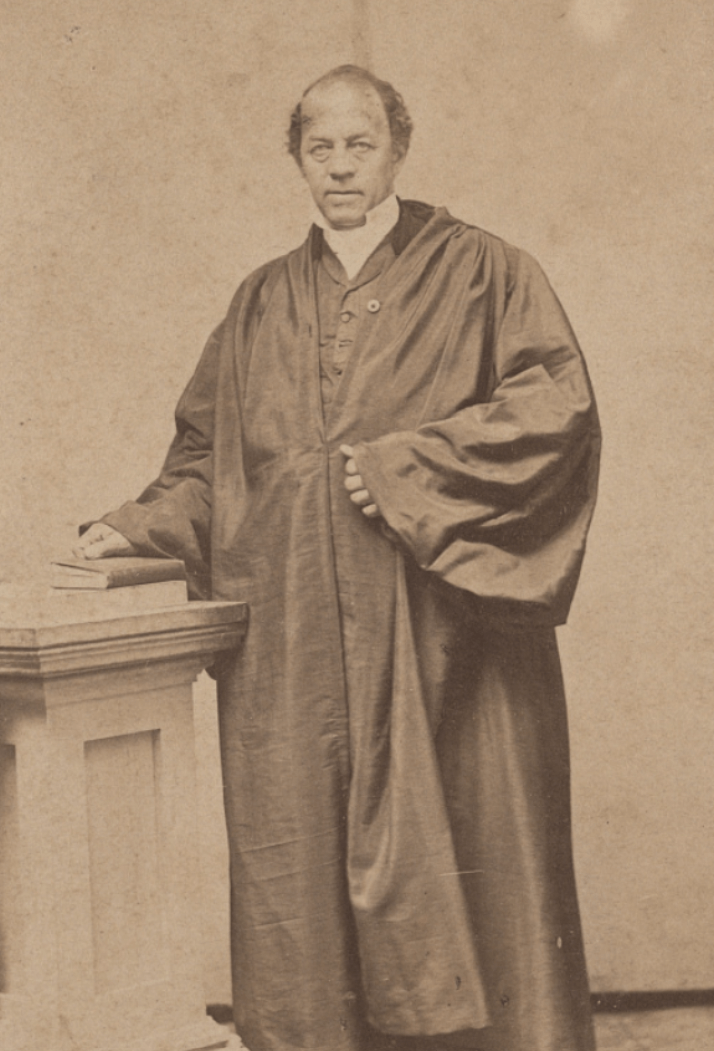

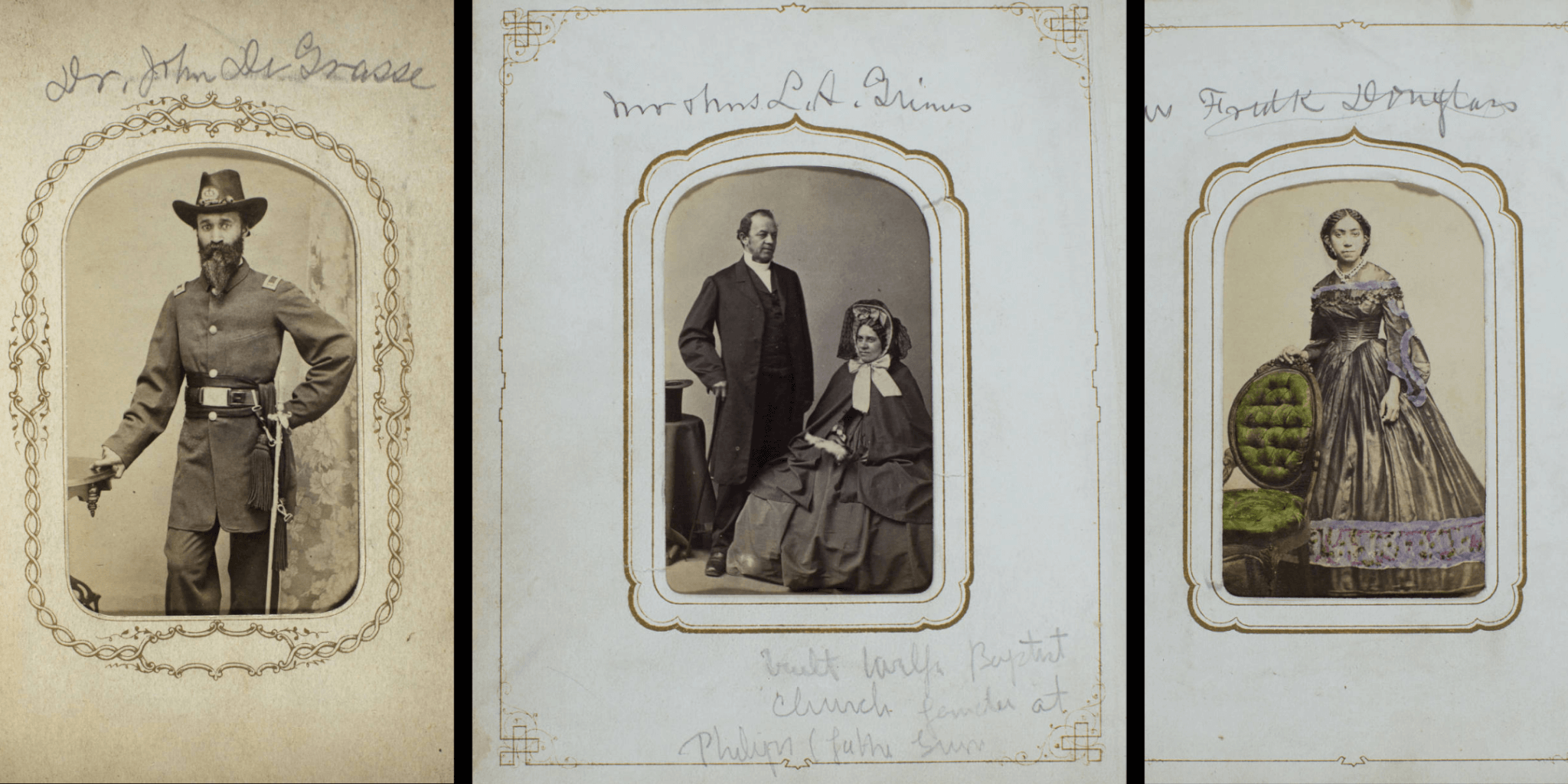

Leonard Grimes was born free in Virginia in 1815. He moved to Washington, D.C. and used his job as a hackman (coachman) to help fugitive slaves escape from Virginia. In March of 1840, Grimes was convicted on circumstantial evidence of having helped seven slaves from Loudoun County, Virginia escape in his coach to D.C. He spent two years doing hard labor in Richmond Penitentiary, and moved with his wife, Octavia Grimes, to New Bedford, Massachusetts shortly after.

Grimes was approached by the “little band” worshipping in Smith Court and, after a visit, was offered a three-month stint as the congregation’s minister. He proved to be popular: when his short term ended, the congregation urged Grimes to stay and move to Boston, and offered him a salary of $100 per year. Grimes agreed. The company was officially organized as the Twelfth Baptist Church on April 24th, 1848, and Grimes was ordained as pastor on November 24th that same year.

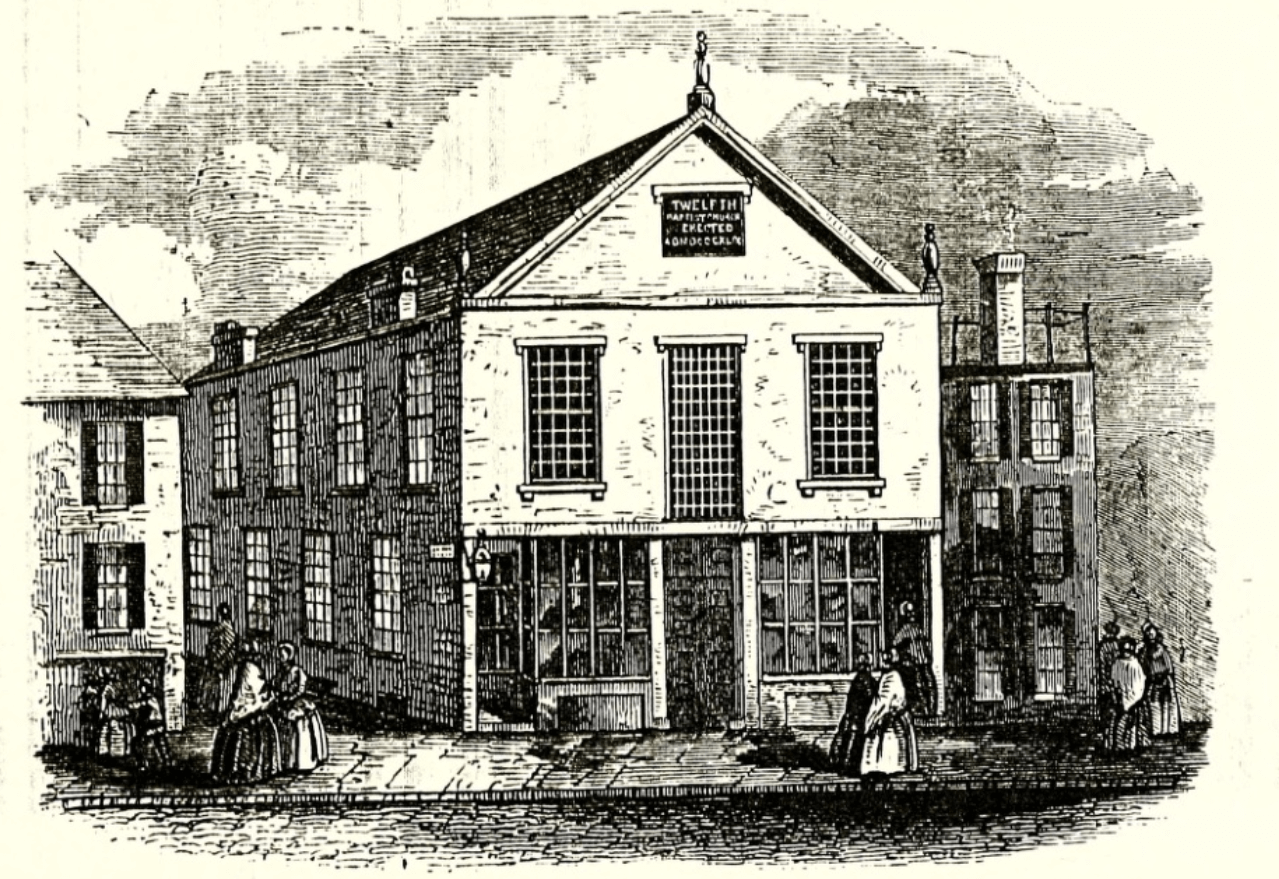

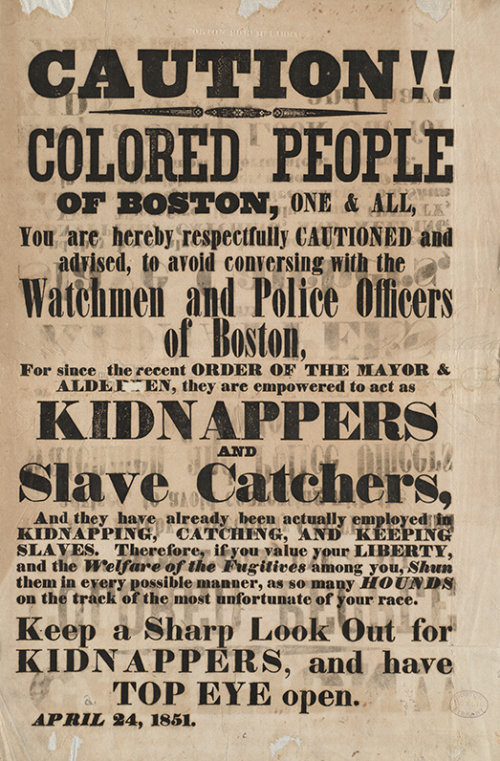

Grimes’ first order of business was to find a new site: the current rooms in Smith Court were becoming too small for the congregation’s quickly increasing membership. He decided on a lot on Southac Street (today, 43-47 Phillips Street) just a few blocks away from their current location, and still on the north slope of Beacon Hill. The trustees purchased it in early 1849, and committed to spending no more than $10,000 on the building, raising money in equal measure from the membership, a loan, and through donations by the Christian public. Construction began in August 1850, but was brought to a halt by the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act less than two months later. The new, more severe Fugitive Slave Law, a part of the Compromise of 1850, mandated that freedom seekers be returned to their enslavers without due process. The law “struck the church like a thunderbolt, and scattered the flock” – the Twelfth Baptist lost over 40 of its members who, fearing capture, fled to the safety of Canada. In his history of the church, George Washington Williams poignantly describes these months in the latter half of 1850:

Gradually the walls of the [Twelfth Baptist Church] edifice grew heavenward, and the building began to take on a pleasing phase. At length the walls had reached their proper height, and the roof crowned all. Their sky was never brighter. It is true that a “little speck of cloud” was seen in the distance; but they were as unsuspicious as children. The cloud approached gradually, and, as it approached, took on its terrible characteristics. It paused a while; it trembled. Then there was a deathlike silence in the air, and in a moment it vomited forth its forked lightning, and rolled its thunder along the sky. It was the explosion of a Southern shell over a Northern camp, that was lighted by the torch of ambition in the hands of our fallen Webster. It was the culmination of slave-holding Virginia’s wrath. It was invading the virgin territory of liberty-loving Massachusetts. It was hunting the fugitive on free soil, and tearing him from the very embrace of sweet freedom… It seemed as if they were to lose their house of worship. It was a sad and memorable period. Public sympathy ceased to flow. The hand of charity was paralyzed. The whole North was stunned.

Though the “hand of charity was paralyzed,” Reverend Grimes remained determined. As Williams wrote, during this time, “it was almost a miracle to find a pulpit or church openly assailing slavery. But it was not so with the Twelfth Baptist Church or pulpit. Their house was not simply dedicated to the service of God in song and prayer and discourse. It was the home of the oppressed, the vantage ground of the champions of human freedom.” Grimes spearheaded this defiant movement, mobilizing Boston’s Black community in response to the Fugitive Slave Act. Grimes and his congregation raised funds to aid freedom seekers, and many chose to remain with the Twelfth Baptist Church. Boston Vigilance Committee records show that Grimes was reimbursed for helping numerous freedom seekers on their passage to Canada and other locations.

At the same time, the church vestry had been completed, using the $4,500 the church had spent so far on construction, allowing the congregation to commence worship in the space in 1851. With many self-emancipated slaves and active abolitionists among its members, the Twelfth Baptist became known as “The Fugitive Slave Church.” Those who worshipped there included Lewis and Harriet Hayden, Shadrach Minkins, Anthony Burns, Thomas Sims, Christiana Carteaux and Edward Mitchell Bannister, and Peter Randolph.

Grimes, often with the help of other members of the Twelfth Baptist Church, was involved in every major fugitive slave case during this period, including those of Shadrach Minkins, Thomas Sims, and Anthony Burns. When Sims was arrested and held at the Boston Court House in April 1851, Grimes sent to inform him that mattresses were placed beneath his third-floor window, so that he could escape. (This plan was thwarted when officers barred the window.) Grimes then called upon the congregation to try to purchase Sims’ freedom, but the $1,800 raised was not enough and Sims remained enslaved until the Civil War. Grimes was also with Shadrach Minkins, a member of his congregation, during the courtroom siege that secured his freedom in February 1851. Further, Grimes and Twelfth Baptist deacon Coffin Pitts advised Anthony Burns during Burns’ stay in Boston in the spring of 1854. After Burns was ordered to be returned to Virginia, Grimes and his congregation raised $1,300 in 1855 to purchase his freedom, and Grimes traveled to Baltimore personally to arrange Burns’ funds and manumission papers.

In 1855, the Twelfth Baptist Church building was finally completed, “a neat and commodious brick structure, two stories in height, and handsomely finished in the interior.” Its congregation was also continuing to grow rapidly under Grimes’ leadership. In 1848, when the church joined the Boston Baptist Association, it ranked 20th out of 22 churches in terms of membership. A decade later, it was ranked 9th out of 32 churches, with 267 members. By 1870, it had become the largest in the Association; with 630 members, it surpassed even the First Baptist Church. And by 1873, it had over 700 members, as (according to Williams) “many from the South, learning of the good name of Rev. Mr. Grimes, sought his church when coming to Boston.”

Grimes’ activism continued into the Civil War. He held a meeting at the Twelfth Baptist Church in 1861 to encourage the enlistment of Black soldiers, which helped to spark the later creation of the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment (1863), one of the first Black regiments to serve in the U.S. Civil War. In 1862, Harriet Tubman attended a meeting in her honor at the Church and addressed the congregation. A year later, in January 1863, members of Boston’s Black community gathered at the Twelfth Baptist to celebrate President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Frederick Douglass, who was there that night, recalled that the “church was packed from doors to pulpit, and this meeting did not break up till near the dawn of day. It was one of the most thrilling occasions I ever witnessed, and a worthy celebration of the first step on the part of the nation in its departure from the thraldom of ages.” After the war, Grimes continued as pastor until his death in 1874; ultimately, he guided the church through a quarter-century of profound growth and activism.

Despite the loss of Grimes, the Twelfth Baptist Church continued to be a significant social and political meeting space. In 1887, prominent members of Boston’s Black community met at the church to found the West End Woman Suffrage League, whose members included Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, Lewis Hayden, Butler Wilson, Eliza Gardner, and Arianna Sparrow.

By the late 19th century, many members of the Twelfth Baptist Church had begun to move to Boston’s South End and Roxbury. In 1906, the church followed, relocating to Shawmut Avenue in Roxbury, and later to Warren Street in 1958, where it remains today. The Southac Street lot was sold to a Jewish congregation – the first location of the Vilna Shul.

The physical building that housed the Twelfth Baptist Church on the West End’s Southac (Phillips) Street for over half a century no longer stands. Nevertheless, the Twelfth Baptist congregation and its new home in Roxbury continued (and continue) to be an important social, political, and religious site for Boston’s Black community. More than a century after its founding and its involvement in Boston’s abolitionist movement, the church—led by Reverend Dr. Michael E. Haynes—was a powerful force in the Civil Rights Movement. Indeed, from 1951 to 1954, a young doctoral student at Boston University attended services and preached at the Twelfth Baptist Church: Martin Luther King Jr.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: John Hope Franklin, “George Washington Williams: The Massachusetts Years,” American Antiquarian Society (1982); Kathryn Grover and Janine V. da Silva, Historic Resource Study: Boston African American National Historic Site (2002); George A. Levesque, “Inherent Reformers-Inherited Orthodoxy: Black Baptists in Boston, 1800-1873,” The Journal of Negro History 60, no. 4 (1975): 491–525; National Park Service, “Black Churches of Beacon Hill,” “Emancipation: A Boston Celebration,” “Harriet Tubman’s Boston: 1862,” “Leonard Grimes,” and “Site of Twelfth Baptist Church”; Lorraine Roses, “After Abolition: Church,” Boston Black History (2006); George Washington Williams, History of the Twelfth Baptist Church, Boston, Mass., from 1840 to 1874: with a statement and appeal in behalf of the church (Boston: James H. Earle, 1874).