Victory Village: The Story of the South End’s Villa Victoria

During the mid-20th century, Boston targeted the South End for urban renewal, alongside the West End and other low-income communities across the city. Responding to impending displacement, the South End’s Puerto Rican residents organized to take control of their community’s destiny, forming the Emergency Tenants’ Council (ETC) and successfully negotiating the right to redevelop the land themselves. The result was Villa Victoria—a community-planned and operated housing development that would become the center of Latino life and culture in the South End. Unlike top-down redevelopment schemes that displaced residents, as happened in the West End, Villa Victoria emerged from the community’s own vision and struggle.

Boston’s South End stands today as one of the city’s most distinctive neighborhoods, characterized by its iconic red-brick row houses, tree-lined streets, and vibrant cultural tapestry. However, the neighborhood’s path to its current status was marked by periods of dramatic change, urban renewal controversies, and powerful community activism that created one of Boston’s most remarkable community development success stories: Villa Victoria.

The Evolution of the South End

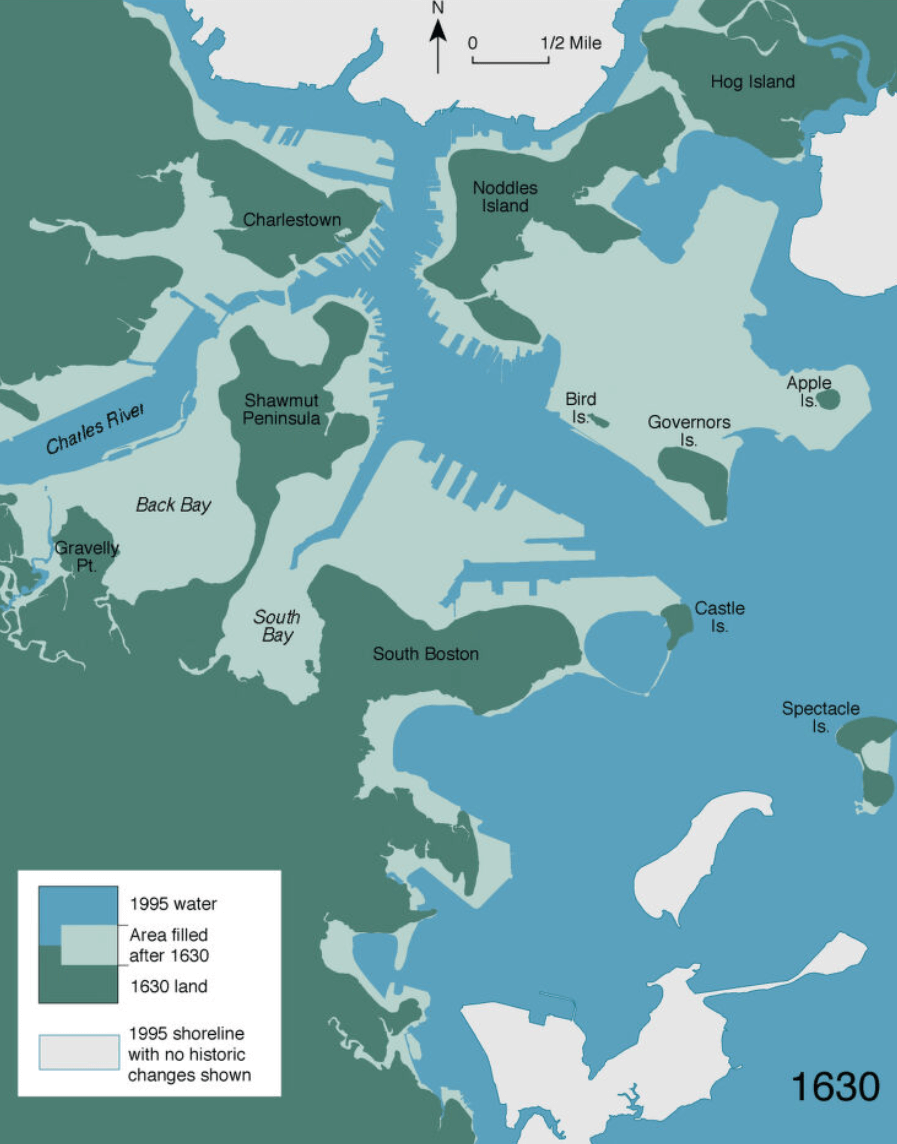

The South End, originally an area made up primarily of mudflats and marshes, was filled in as part of larger Boston landmaking efforts between the early 1800s and 1870. Initially developed in the mid-19th century as an upscale residential district for affluent merchants and businessmen, the area featured uniform red-brick row houses and quaint streets designed around elegant parks and squares.

However, the neighborhood’s fortunes changed rapidly after the Panic of 1873. The once-exclusive district quickly transformed into a working-class enclave, with formerly grand homes subdivided into lodging houses and apartments. By 1900, the South End had evolved into one of Boston’s most diverse neighborhoods, welcoming wave after wave of immigrants. Jews, Syrians, Greeks, Italians, Portuguese, Chinese, West Indians, and African Americans all established communities there, creating what was described as a “vibrant, economically poor but culturally rich, dynamic community.”

The post-World War II era brought significant challenges. Suburban flight, disinvestment, and structural deterioration accelerated the South End’s physical decline. The older immigrant population dwindled, while the neighborhood saw growth in its Black population and new arrivals from Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic, particularly around the West Newton Street area in the 1960s and 1970s.

Urban Renewal and Community Response

During the mid-20th century, Boston targeted the South End for urban renewal, alongside the West End and other low-income communities across the city. The first wave in the 1950s demolished the New York Streets area, displacing many Jewish, Italian, and West Indian families. Similar redevelopment in neighboring Chinatown pushed Chinese residents into parts of the South End. Additional urban renewal projects, including Castle Square and Cathedral Veterans Housing Projects, razed entire blocks of 19th-century housing to make way for new multi-family developments.

By the late 1960s, the South End’s Black and Puerto Rican residents found themselves fighting displacement through community organizing and public protests. One particular section of the South End—an area of dilapidated brownstones derogatorily labeled “Skid Row,” where many Puerto Rican residents lived—was slated for demolition by the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), with plans to replace it with luxury housing.

The Villa Victoria Story

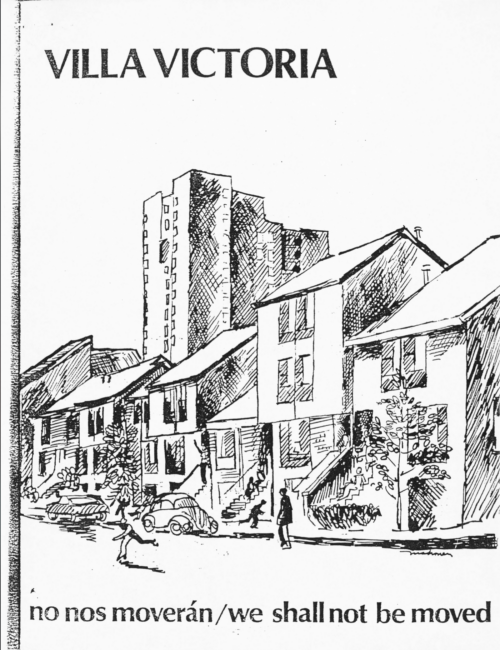

In response to looming displacement, the Puerto Rican residents organized to take control of their community’s destiny. They formed the Emergency Tenants’ Council (ETC) and, with support from various activists and organizations, successfully negotiated the right to redevelop the land themselves.

The result was Villa Victoria (Victory Village)—a community-planned and operated housing development that would become the center of Latino life and culture in the South End. What makes Villa Victoria extraordinary is that it wasn’t simply an affordable housing project; it represented a powerful moment of community self-determination and cultural preservation.

Managed by Inquilinos Boricuas en Acción (IBA), the development features more than 500 affordable housing units made with thoughtful architectural elements. Designed by John Sharratt Associates, the complex includes community gardens, a central plaza reminiscent of traditional Puerto Rican town squares, and houses specifically planned to encourage social interaction among residents.

A Model of Community Participation

During the mid-1970s and early 1980s, Villa Victoria exemplified successful community participation, hosting frequent communal activities, a community-run television channel, and an engaged resident board. The complex hosted cultural programs and established the largest Latino arts center in New England.

What set Villa Victoria apart from other urban renewal projects was its grassroots origins and community control. Unlike top-down redevelopment schemes that displaced residents, as happened in the West End, Villa Victoria emerged from the community’s own vision and struggle. It transformed what could have been another story of displacement into one of empowerment and community building.

Research by sociologist Mario Luis Small has shown that Villa Victoria challenged prevailing theories about concentrated poverty. Contrary to expectations that poverty would lead to social isolation and community disintegration, Villa Victoria had a rich, dynamic social environment with high levels of community participation.

Gentrification and Changing Demographics

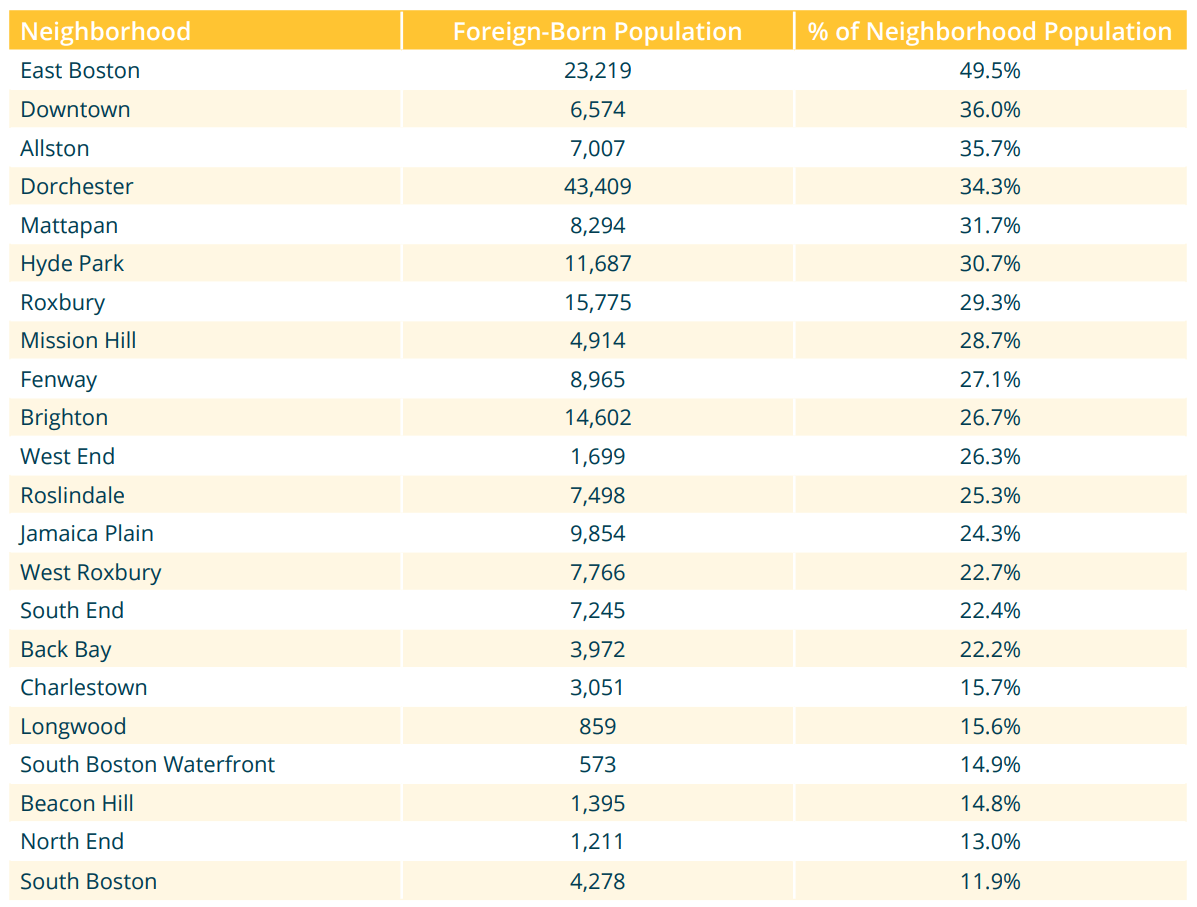

Despite the success of Villa Victoria, the broader South End neighborhood has undergone dramatic demographic shifts since the 1970s. Ongoing development projects and rampant gentrification have driven most low-income families and newer immigrants away from the area. Property values have skyrocketed, meaning that outside of a few subsidized housing developments like Villa Victoria, only prosperous immigrant professionals can now afford to live there.

Although the South End retains elements of its historical diversity, it now has a lower percentage of foreign-born residents than the city of Boston as a whole. What was once a neighborhood characterized by economic diversity and immigrant accessibility has transformed into one of Boston’s most desirable and expensive districts, with its preserved Victorian architecture and upscale amenities attracting wealthy residents.

Legacy and Challenges

While Villa Victoria’s success demonstrated the power of community-led development, maintaining its initial level of community engagement has proven challenging over time. As original residents who fought for the complex were gradually replaced by new residents who didn’t experience the struggle for Villa Victoria’s creation, the sense of community and motivation for participation evolved.

Despite these challenges, Villa Victoria remains a powerful testament to community resilience and the potential of grassroots urban development. Currently, IBA is constructing a new building within Villa Victoria: La CASA (The Center for Arts, Self-determination and Activism) is a 26,000 square-foot, $33 million project to create a vibrant hub for Latino cultural preservation, which is expected to open in 2026.

In 1973, the South End was listed on the National Register of Historic Places for having the largest number of intact Victorian row houses in the United States. A decade later, the 500-acre neighborhood was declared a Landmark District by the city of Boston. Today, the South End stands as an example of both preservation success and the complex consequences of urban revitalization—with Villa Victoria continuing to serve as a living monument to a community that refused to be displaced and instead created its own vision of urban renewal while preserving affordability in an increasingly exclusive neighborhood.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Boston Landmarks Commission, The South End: District Study Committee Report (Revised November 14, 1983); The Boston Planning & Development Agency, Boston by the Numbers, 2020; Global Boston, “The South End,” Boston College Department of History; Russ Lopez, Boston’s South End: The Clash of Ideas in a Historic Neighborhood (Shawmut Peninsula Press, 2015); Anthony Mitchell Sammarco, Boston’s South End (Arcadia Publishing, 2004); Mario Luis Small, “Can Social Capital Last? Lessons from Boston’s Villa Victoria Housing Complex,” Policy Brief Volume I, Number I, October 2004, Rappaport Institute for Greater Boston, Harvard Kennedy School; Mario Luis Small, Villa Victoria: The Transformation of Social Capital in a Boston Barrio (University of Chicago Press, 2004).