The Charles Street Jail

Charles Street Jail stands as a landmark of major national significance, both as a key example of the Boston Granite Style of architecture and as the embodiment of mid-nineteenth-century penal reform movements. The jail’s history was marked by dramatic shifts: initially celebrated as an architectural and reformist triumph at its opening in 1851; later decried for its “cruel and unusual” conditions in the 20th century, prompting its closure; before being reinvented as a luxury hotel in the 21st century.

When the Charles Street Jail closed its doors in 1990, it was goodbye and good riddance. Perched at the busy intersection of Charles Street, Cambridge Street, and Storrow Drive, the jail was a relic of old Boston, a decrepit facility ordered to close 17 years earlier because of its unsanitary conditions. Built in the mid-19th century and one of the few structures to survive West End urban renewal, the jail was a security embarrassment, frequently making headlines for the slew of inmate escapes, as the facility epitomized the outdated infrastructure and declining civic institutions of the mid-20th century city.

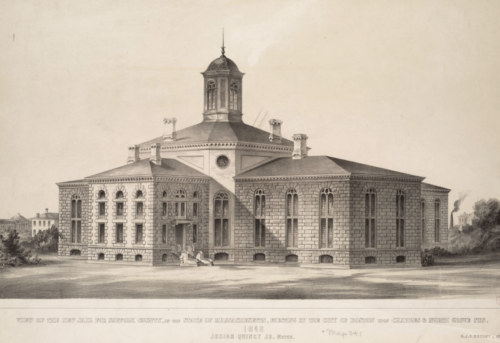

But the Charles Street Jail—officially called the Suffolk County Jail—was celebrated as a landmark architectural achievement when completed in 1851. The building was designed by Gridley J.F. Bryant, a second-generation Boston architect whose father built the Bunker Hill Monument. He designed the jail in the shape of a cross, with four wings and a central rotunda. Its segmented arches, rough stone facades, and 33-foot-tall windows were inspired by Italian Renaissance and Gothic Revival architecture. Other New England jails would emulate Charles Street’s cruciform style, and Bryant went on to design Old City Hall and Arlington Street Church, both Boston architectural staples.

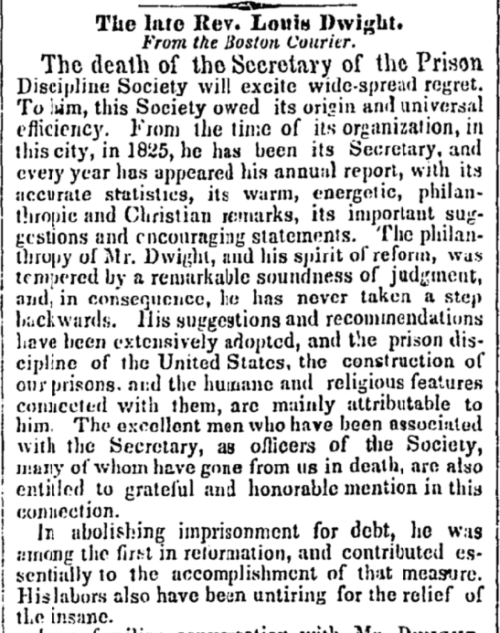

Reverend Louis Dwight also played a key role in the jail’s planning and design. As the founder of the Boston Prison Discipline Society in 1825, Dwight was a vocal advocate for prison reform. Existing American prisons were centered around solitary confinement, but a competing philosophy known as the Auburn System focused on rehabilitation rather than punishment. Dwight and Bryant planned Charles Street Jail to maximize the goals of the Auburn System, where inmates would reenter society as industrious and law-abiding citizens.

The 220 cells held over 2,300 inmates in its first six months of operation. All cells were single occupancy, eight feet wide, eleven feet long, and ten feet high. The cruciform design allowed for security guards to monitor the four wings from the central rotunda. The Auburn System called for a regimented daily routine with constant supervision and congregate labor. In 1888, the National Prison Association named it the best jail in the United States.

Like much of modern Boston, the Charles Street Jail was built on landfill, and the encroaching coastline was fortified by granite seawall. Before the construction of Storrow Drive and the conjoining highways, a park called the Charlesbank bordered the jail. Designed by Frederick Law Olmstead, the Charlesbank was the country’s first open air gymnasium, featuring rope climbing, trapezes, pole vaulting, and a track. Despite its proximity to the jail, families were drawn to the park, as it offered a respite of green space amid the urban congestion. The jail became a point of pride for residents who recognized its architectural elegance, and the building was prominently featured in paintings and postcards.

From the time it was completed in 1851, officials from around the country visited the facility, as Bryant’s design had a pioneering influence. The city continually invested in its upkeep, installing plumbing and ventilation in 1897, and building a women’s wing in 1902. The city paid $250,000 in 1921 for the installation of a new hall with medical quarters and an auditorium. When baseball legend Babe Ruth visited the jail in 1926, he (clairvoyantly) remarked, “it isn’t like a jail, it’s like a hotel.”

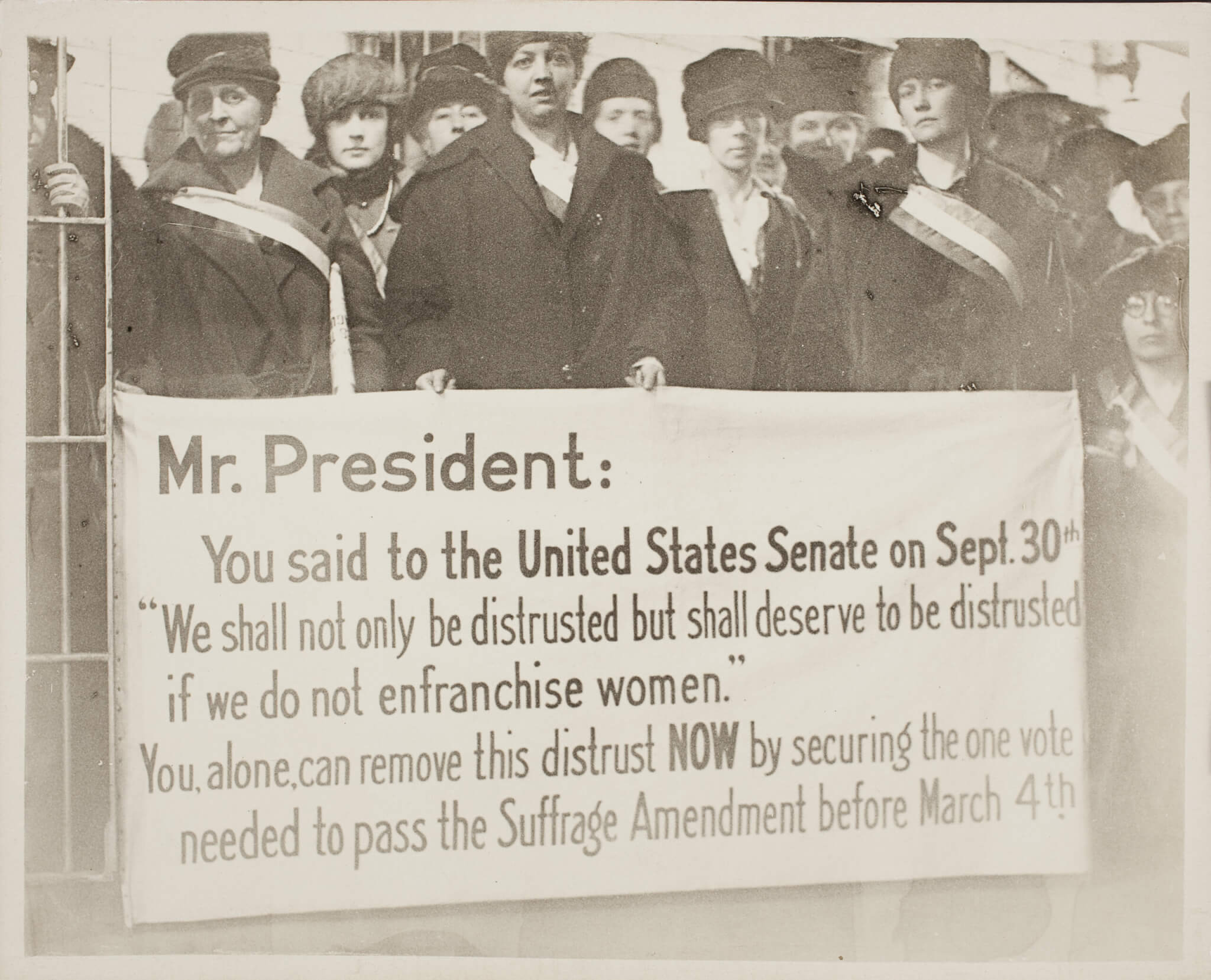

The jail had a diverse array of inmates during its 140-year existence. Crime boss Whitey Bulger spent time at Charles Street in 1955, and Providence gangster Raymond Patriarca served in the 1930s. Six of the eight individuals charged in the Great Brinks Robbery were jailed, as was con man Frank Abagnale, who was portrayed by Leonardo DiCaprio in the 2002 film Catch Me If You Can. Aside from criminals, “free love” advocate Ezra Heywood, civil rights leader William Monroe Trotter, and birth control activist Bill Baird each served short stints. In 1919, 19 suffragists from the National Woman’s Party were arrested for protesting Woodrow Wilson’s visit to the city; 13 refused to pay fines and spent time at the Charles Street Jail. Future mayor James Michael Curley was jailed in 1904 after taking the civil service exam for a friend. Nineteenth-century businessman and noted eccentric, George Francis Train, did 15 stints at Charles Street—often on his own volition—as he reportedly enjoyed the accommodations.

The only other person on record who voluntarily spent time at Charles Street Jail was Judge Arthur Garrity, who in 1973 stayed a night to evaluate the conditions of the jail. Garrity was appalled by what he witnessed, calling the jail “a violation of constitutional rights,” and ordered that no future inmates be sentenced to Charles Street.

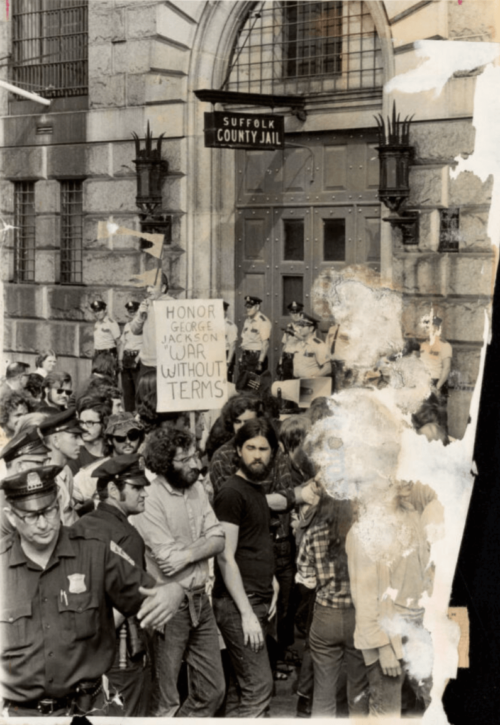

The impetus for the visit came after inmates filed a lawsuit, claiming the jail was cruel and unusual punishment, citing the corroded toilets, decaying walls, inadequate heating, and double occupancy of cells. The early 1970s were marked by riots and protests from the prisoners, one of which resulted in $250,000 in damages after inmates found bugs in their soup. There were security scares, with inmates escaping by sawing through bars, using empty barrels to climb walls, and knotted blankets to descend to the ground. The Boston Globe wrote that “the 1960s were harvest years for escapees.”

The Charles Street Jail officially closed its doors in 1990 and the Nashua Street Jail served as the replacement Suffolk County facility, with Mass General Hospital taking control over the then-vacant property in a land swap. Ten years earlier, the Boston Landmarks Commission designated the building a historical landmark, and any redevelopment had to comply with preservation restrictions. In 2001, the development firm Carpenter & Company, along with the architectural firms Cambridge Seven Associates and Ana Beha Architects, were selected to refurbish the building and turn it into a luxury hotel, and in 2007, the (ironically named) Liberty Hotel opened its doors.

The project was a shining example of adaptive reuse. The developers preserved the jail’s central rotunda, which now serves as the hotel’s lobby, while maintaining the exposed bricks, arched windows, and catwalks. The hotel includes bars called “the clink” and “alibi.” The $150 million renovation aligned with Boston’s civic, historical, and developmental goals, and the Liberty Hotel joins a handful of American hotels converted from jails, including the Jail Hill Inn in Galena, Illinois and the Jailhouse Inn in Newport, Rhode Island.

The Charles Street Jail survived West End Renewal because of its function as a correctional facility, and after its utility was extinguished, the city ensured the building’s history wasn’t forgotten. Despite the renovation’s popularity, former inmates likely view it differently, remembering the squalid and uninhabitable conditions, and prison reform activists might question why a dysfunctional jail is celebrated. But preserving the Charles Street Jail ensures memory of both its lofty reformist beginnings and disreputable end, exemplifying how history doesn’t often exist on a good-evil binary and offering a point for reflection on the current state of American criminal justice.

Article by Neil Iyer, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: David Arnold, “Locking up Charles Street Jail’s Colorful Past,” The Boston Globe, July 18, 1991; Boston Landmarks Commission, “Report of the Boston Landmark Commission on the Potential Designation of the Suffolk County Jail as a Landmark” (1978); Boston Women’s Heritage Trail, “Charles Street Jail”; Christina Gagliano, “Liberty at Last: An Ironic History of the Charles Street Jail and Its Architect,” Travel Through History (March 24, 2024); Alison Gregor, “A Room for the Night (Not 40 to Life),” The New York Times, March 18, 2007; Robert Battin McCay, “Charles Street Jail: Hegemony of a Design,” Doctoral Thesis, Boston University (1980); Joseph McMaster, Charles Street Jail (Arcadia Publishing, 2015); Vanessa Nason, “Best of Boston All-Stars: What’s New at the Liberty Hotel,” Boston Magazine, January 13, 2016; Max Page and Paul Johansen, “Landmarks of Punishment: Eastern State and Charles Street,” Places Journal (2010); Ray Richard, “Nashua Street Jail Opens; Will Replace Charles Street,” The Boston Globe, May 3, 1990; Kara Zelasko, “Preservation and Commodification at the Former Charles Street Jail,” Qubpublichistory, July 16, 2018.