The Fugitive Slave Laws in Boston: Part 2, 1850–1855

This article, part 2 in a series on fugitive slaves in Boston, explores the new legislation passed during the lead up to the Civil War which expanded the reach of the fugitive slave law, and the reactions of Bostonians to slave catchers targeting residents. Part 2 surveys the passing of the controversial Compromise of 1850, the successful escapes of Ellen and William Craft as well as Shadrach Minkins, and the violent reactions to the returns of fugitive slaves Anthony Burns and Thomas Sims.

The Fugitive Slave Law of 1850

In 1850, the United States faced a political crisis that threatened its very existence. Following mass immigration to Northern cities, the “free states” gained more seats in the House of Representatives. Meanwhile, the new territories California and New Mexico were heading towards admission as free states. This threatened the South’s position in the Senate. Since the Missouri Compromise of 1820, there had been a balance between slave and free states. Each state had two senators which allowed slave states to vote down legislation that threatened their “property.” A free California and New Mexico would upset this careful balance of power. Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina warned that these events would give the South no choice but to leave the union to preserve its slave economy.

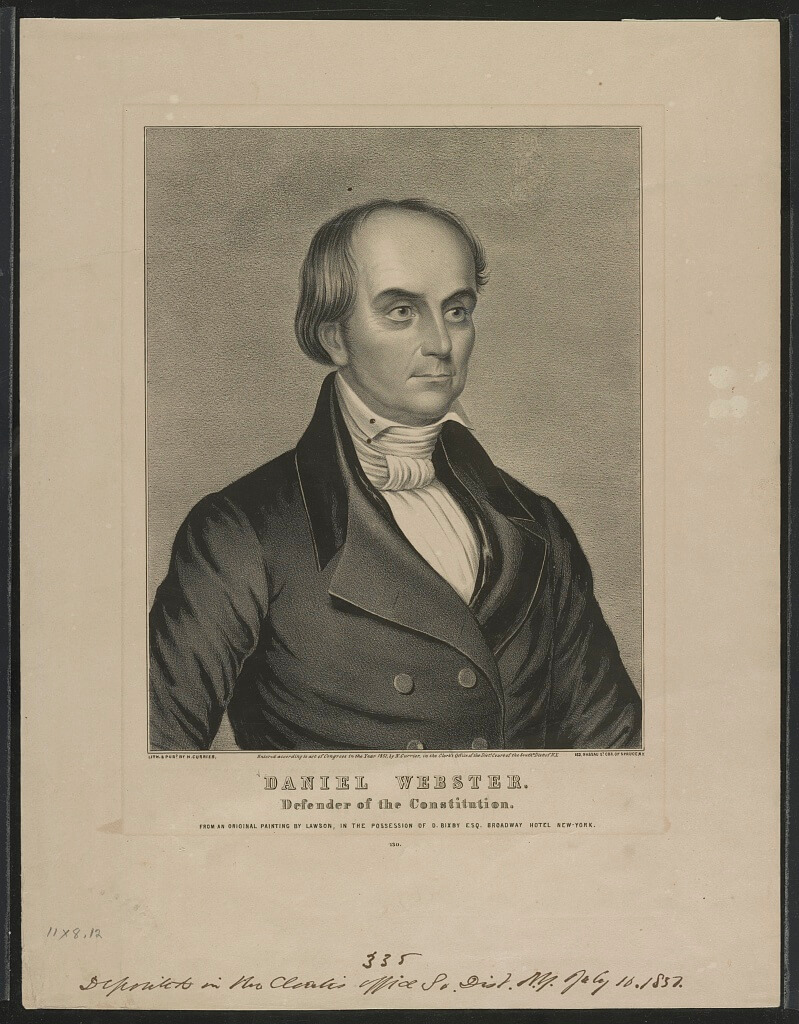

Calhoun, along with Senators Henry Clay of Kentucky, and Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, proposed a compromise. They hoped to appease both sides and hold the nation together. The pressure to pass the legislation forced Webster to deny some previous personal convictions. Despite declaring slavery a “great moral, social, and political evil” in 1845, Webster admitted he had to side with Clay for the sake of the Union. Webster said “I wish to speak to-day, not as a Massachusetts man, not as a northern man, but as an American, and a member of the Senate of the United States . . . I speak today for the preservation of the Union.” Slavery would continue as Congress eventually passed the Compromise of 1850, which President Millard Filmore signed into law on September 9, 1850. Webster’s arguments were successful, but he received harsh criticism in his strongly abolitionist home state.

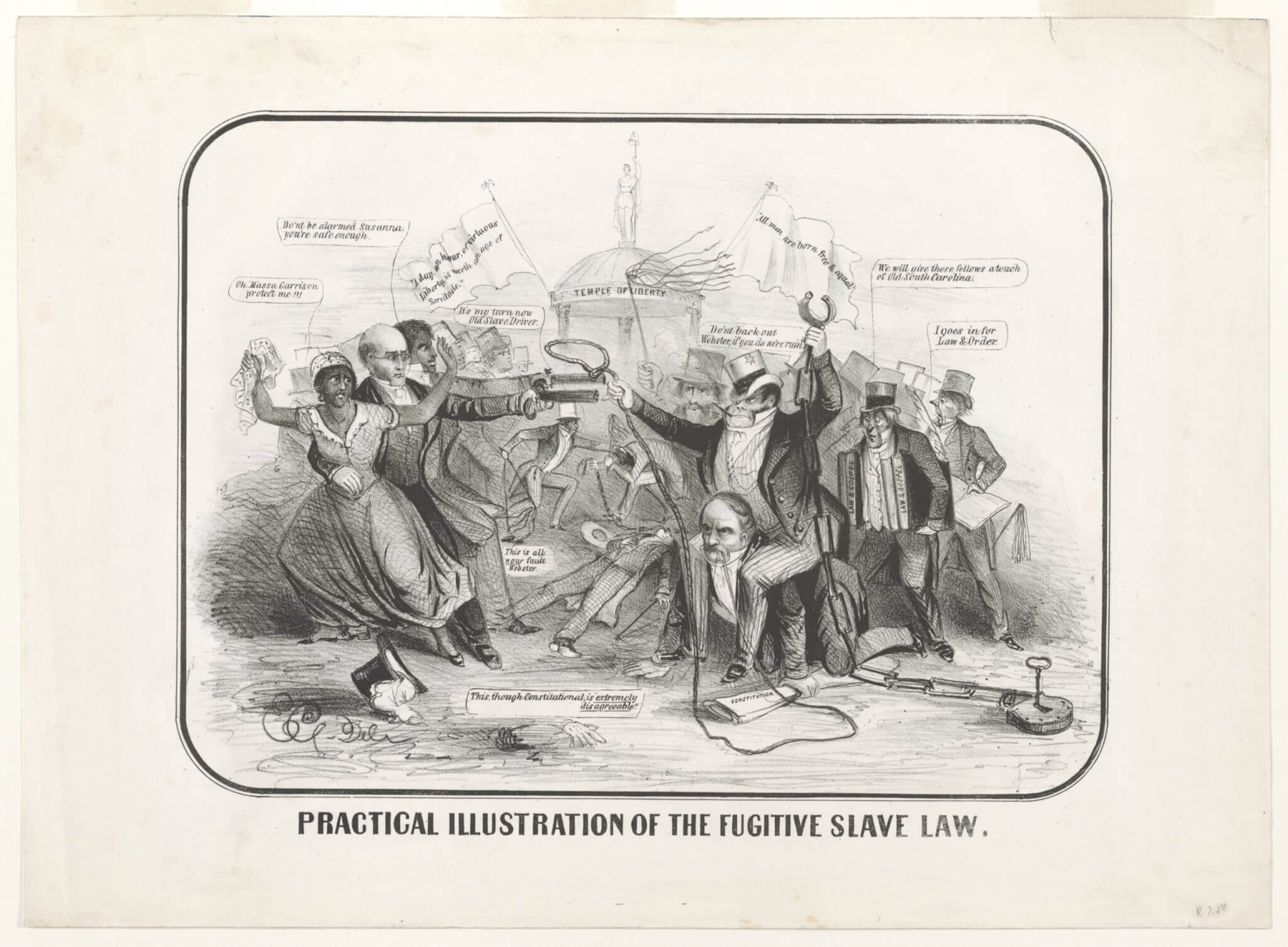

The Compromise included a stronger Fugitive Slave Law. It was a reaction to events such as the Boston Abolition Riot and the activities of Boston groups like the Freedom Association. The new law gave more power to the federal court system and allowed U.S. Marshals to deputize citizens. It also increased penalties for those interfering with or refusing to cooperate with the slave-catching process.

Slave catchers often had difficulty finding court officials to process their cases. The new law reminded federal judges that they had a responsibility to quickly process fugitive slave cases. The law encouraged convictions by guaranteeing judges payments of $10 if they approved the return of the slave and only $5 if not. Lastly, according to the new law “in no trial or hearing under this act shall the testimony of such alleged fugitive be admitted in evidence.”

Federal marshals could now “summon and call to their aid the bystanders, or posse comitatus of the proper county, when necessary to … ensure conformity with the provisions of this act.” Marshalls themselves could be fined up to $1000 for not complying with the law, and were liable for the “value of the service or labor” of the fugitive if that fugitive should escape their custody.

As in the earlier fugitive slave law of 1793, it was illegal for an individual to “knowingly and willingly obstruct, hinder, or prevent” the arrest of “ a fugitive from service or labor. But the 1850 law increased the fine to $1000, while reducing the possible prison term to six months. This new law, for the first time, forced Bostonians to actively engage in the slave catching process.

After news of the new law broke, the Black community, as well as their white abolitionist allies, took action. At a meeting in Faneuil Hall, roused by the words of Frederick Douglass, abolitionists formed the Boston Vigilance Committee. The committee would “take all measures that they shall deem expedient to protect the colored people of this city in the enjoyment of their lives and liberties…”. Committee members aided fugitive slaves passing through the city. They helped those on their way to freedom in Canada by giving them supplies, legal and medical aid, and shelter in Boston. They issued warnings to formerly enslaved residents who might be targeted. Moreover, they attempted many daring rescues of those who had been arrested before they were returned to slavery.

These acts of resistance were often illegal, but the abolitionist community in Boston bravely defied the law in order to protect others’ natural right to freedom. They fought against duly enacted laws which they saw as unjust and immoral. As one member of the newly founded Vigilance Committee resolved, “Constitution or no constitution, law or no law, we will not allow a fugitive slave to be taken from Massachusetts.”

Resistance to the Fugitive Slave Law in Boston

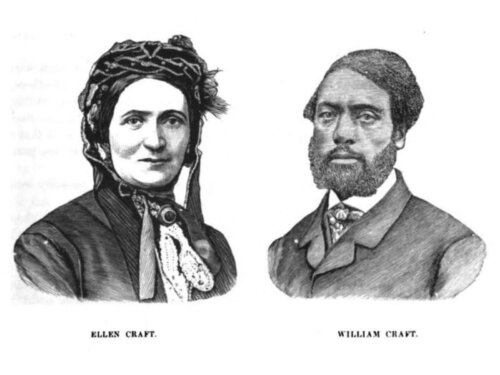

Boston’s Black community and abolitionists continued to rise to the defense of escaped enslaved people living in the city. In some cases they were successful. Ellen and William Craft had escaped to freedom in Boston before the new fugitive slave law. Later, the Vigilance Committee and other abolitionists helped the Crafts avoid capture and escape to freedom in England. Black abolitionists grabbed Shadrach Minkins, another escaped slave, at his hearing and whisked him out of the courthouse to safety. He traveled between the houses of various abolitionists until he reached Canada.

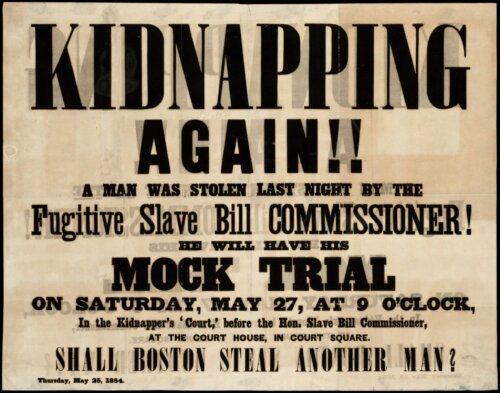

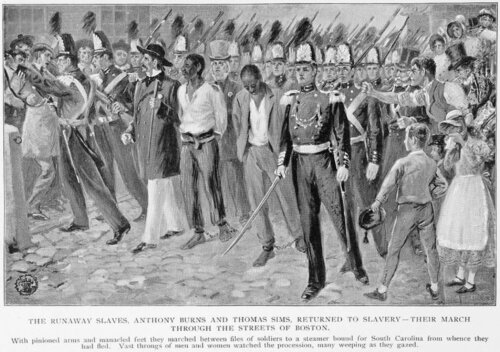

Other Boston fugitives weren’t so lucky. Both Thomas Sims and Anthony Burns were captured and held in jail in anticipation of their hearings. Despite attempts to free Sims and a riot by those sympathetic to Burns, both were returned to slavery. The rescue attempts for both men and the vicious public response by many in Boston against the slave catchers were a spectacle. These cases contributed to increasing anger against slavery and popularity of the abolitionist cause.

The Anthony Burns incident in particular received national attention because of the volume of support for Burns. The level of violence involved in the riot that followed resulted in Irish volunteer federal deputy James Batchelder’s death. The riots over Burns’ arrest converted many to the abolitionist cause. It also led to the passage of the Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act of 1855 which made it all but impossible for slave catchers to pursue escaped enslaved people in the state. As Amos Adams Lawrence recalled: “We went to bed one night old-fashioned, conservative, Compromise Union Whigs and waked [sic] up stark mad Abolitionists.”

Resistance to the fugitive slave law by both Black and white abolitionists in Boston was one of the ways the abolition movement gained momentum. Many had witnessed their formerly enslaved neighbors taken from their communities with their own eyes. This was enough to push even moderately anti-slavery Bostonians to stand up for everyone’s right to freedom. The people of the birthplace of the American revolution were not about to let their fellow Bostonians be denied the opportunity to pursue life, liberty, and happiness. In the years leading up to the Civil War, Massachusetts would protect its own and eventually assist in the Northern cause of freeing every enslaved person across the county.

Article by Jaydie Halperin and Bob Potenza, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources:

Barbara F. Berenson, Boston and the Civil War: Hub of the Second Revolution (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014); Bill of Rights Institute, Lyndsay Campbell, “The ‘Abolition Riot’ Redux: Voices, Processes,” The New England Quarterly 94, no. 1 (March 1, 2021): 7–46; James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton, Black Bostonians: Family Life and Community Struggle in the Antebellum North (New York: Holmes & Meier, 1999); J. Gordon Hylton, “Before There Were ‘Red’ and ‘Blue’ States, There Were ‘Free’ States and ‘Slave’ States,” Marquette University Law School, November 1, 2011; Jim Crow Museum, “Slavery in America – Timeline”; The Liberator, October 18, 1850; National Constitution Center, “Massachusetts Personal Liberty Act (1855)”; National Park Service, “Faneuil Hall, the Underground Railroad, and the Boston Vigilance Committees”; National Park Service, “The Fugitive Slave Laws and Boston”; Thomas H. O’Connor, Civil War Boston: Homefront & Battlefield (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1999); Mark A. Peterson, The City-State of Boston: The Rise and Fall of an Atlantic Power, 1630-1865 (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 2019); Report of the Boston Female Anti Slavery Society : with a concise statement of events, previous and subsequent to the annual meeting of 1835 (Boston: Published by the Society, 1836)