Boston's Rat Day of 1917: When the West End Joined a Citywide Rodent War

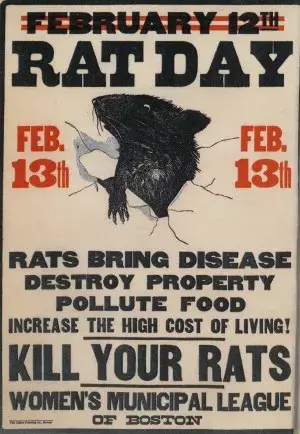

On February 13, 1917, Boston witnessed one of the most unusual civic experiments in its history. The Boston Women’s Municipal League declared war on the city’s rodent population, organizing the first—and as it turned out, only—Rat Day. While this peculiar event captured headlines across the city, it held particular significance for neighborhoods like the West End, where residents had long battled rats in their daily lives.

The Ladies Declare War

The Boston Women’s Municipal League was no ordinary social club. Founded in 1908, this organization of 2,000 well-educated, well-connected middle and upper-class women took on the ambitious mission of civic betterment. Their membership roster was a who’s who of Boston society, featuring names like Adams, Parkman, Coolidge, Sears, Gardner, Cabot, and even Mrs. Louis D. Brandeis.

These women believed that “housekeeping of a great city was women’s work,” just as it was their responsibility to keep their own homes clean. They believed it was their “province to see that the city was kept clean,” ensuring “the garbage and ashes should be promptly and scientifically removed from the streets and alleys, the markets freed from dirt, and dust, and flies, and the air cleaned from soot and smoke.”

By 1917, the League’s Committee on Public Improvements and Sanitation had identified a serious problem: Boston was overrun with rats. They claimed that 750,000 rats infested the city, a staggering number that demanded immediate action. This was roughly equal to the human population of the city according to the 1920 census! The problem was worsening due to subway and Esplanade excavations. This construction drove rats from their traditional haunts to wealthier neighborhoods like the Back Bay. There, they joined the existing populations that had long plagued areas like the West End.

The West End's Rodent Reality

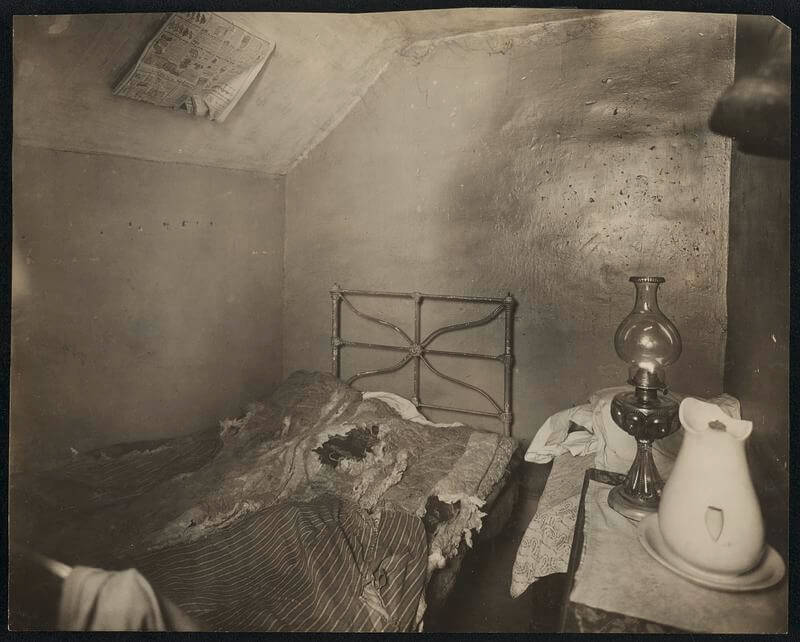

While the Back Bay’s shocked residents were newcomers to the rat problem, West Enders had experience with these unwanted neighbors. The densely populated neighborhood, with its mix of tenements and older buildings, provided ideal conditions for rat populations to flourish.

Forty years after Rat Day, the city would use these sanitary challenges as justification for the West End’s demolition. As documented in the 1957 West End Redevelopment Plan Declaration of Findings, over 60 percent of the structures had rats. They noted other types of vermin, such as mice, roaches, bedbugs, and fleas, in 75 percent of buildings. However, as Claudia Kelty and Stephen Edgell, photographers who documented the West End’s demolition, pointed out, using “rats or cockroaches as even part of an excuse for demolishing a neighborhood is just plain ridiculous. It’s like killing a dog to get rid of the fleas.”

The Campaign Begins

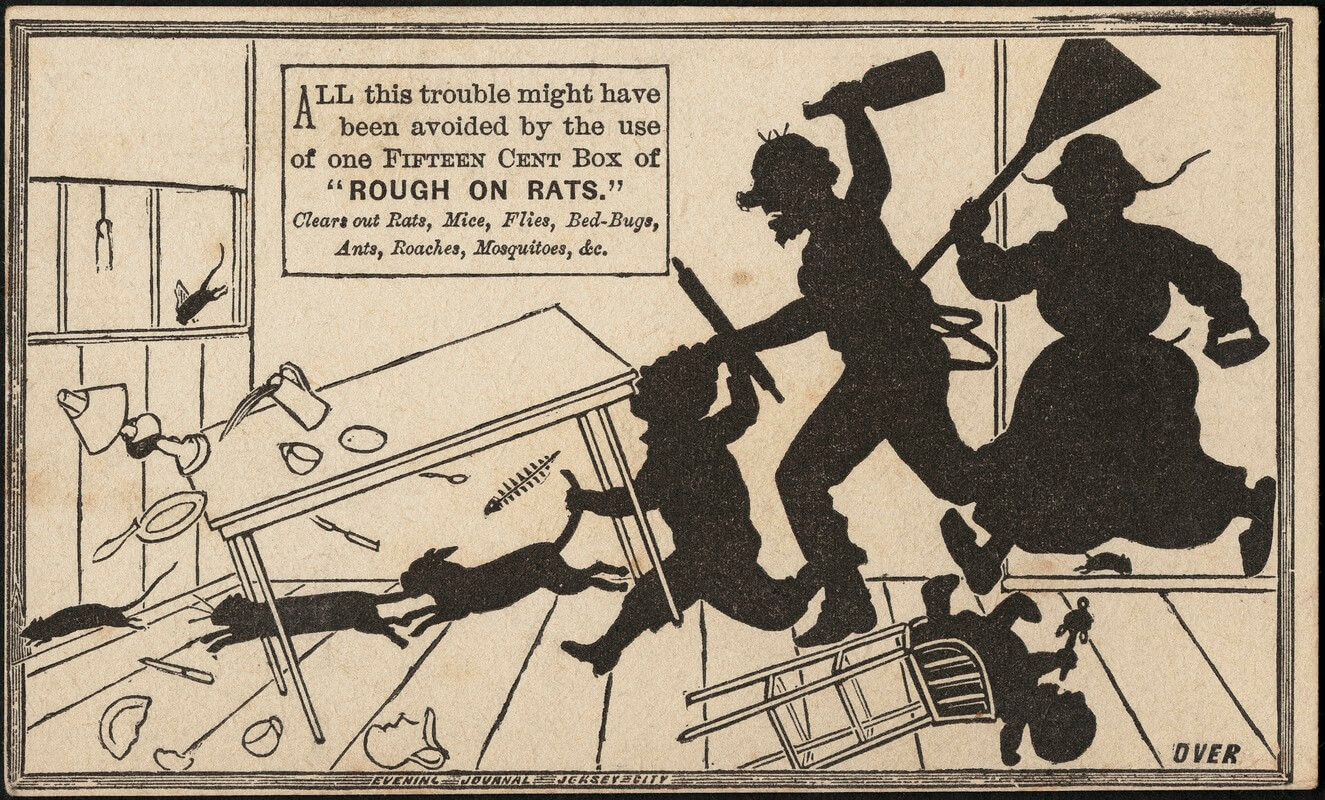

The Women’s Municipal League’s anti-rat campaign was as thorough as a military operation. Under the banner “Kill the Fly, Starve the Rat!”, they launched an extensive education program. The women’s expertise about rat habits and extermination methods spread far beyond Boston. As one slogan read: “If we have to go to New York for our hats, New York comes to Boston to ask about rats.”

The League sent anti-rat literature to every library in the United States and Canada, to scientific libraries in Europe, and to every major newspaper in North America. Requests for their materials came from as far away as Australia, Brazil, India, and Russia. They presented illustrated lectures in high schools and movie theaters, and plastered graphic posters of rats and flies all over the city.

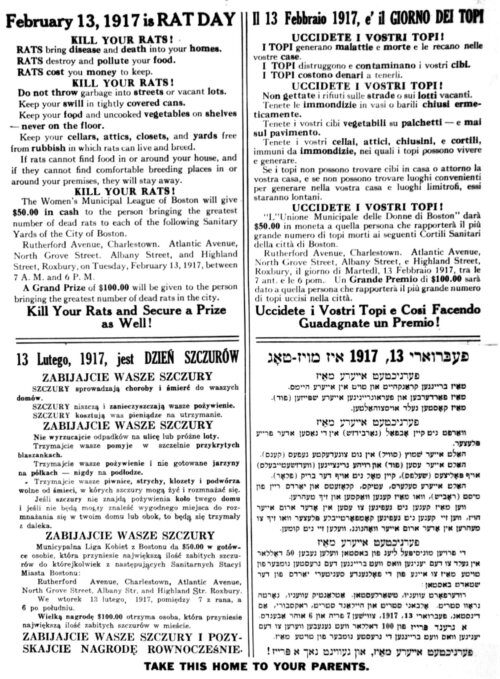

Recognizing Boston’s diverse immigrant population, the League printed their pamphlets in multiple languages – including English, Italian, Polish, and Yiddish – detailing the perils of rats and methods to control their population.

The Great Rat Day Arrives

After extensive preparation, the League organized a citywide extermination program: Rat Day. Mayor James Michael Curley proclaimed Tuesday, February 13, 1917, as “Rat Day” in Boston. It was moved from February 12th after objections that it overlapped with Abraham Lincoln’s birthday. Local newspapers ran stories for weeks in advance, and railroads, stores, business organizations, hotels, and civic groups all supported the effort.

The concept was simple and ambitious. The League set up rat collection points throughout the city and offered prizes for whoever turned in the largest number of rat carcasses. Their inspiration was a similar campaign in London that had allegedly flushed so many rats from the subway system that grey rat skin had become fashionable material for pocketbooks.

The League prepared for a massive collection. They expected enthusiastic participation from residents across all neighborhoods, including the West End, but the day failed to deliver.

Rat Day's Chilly Reception

Rat Day turned out to be a spectacular disappointment. A cold snap days before the event, combined with confusion about the date change, and general public apathy, resulted in the collection of fewer than 1,000 rat carcasses citywide.

The winner of the competition was Mr. Rymkus of Brighton, who single-handedly brought in an impressive 282 rats. He earned $150 in prize money—equivalent to about $3,100 today. Second place went to John White of Charlestown with 88 rats. The League’s campaign had cost $1,339.80, funded by members and public-spirited citizens, making each dead rat quite expensive indeed.

The Women’s Municipal League tried to put a positive spin on the results, with managers telling the Boston Globe that they felt “it was not a failure, since the public is learning.”

While Rat Day marked the end of the League’s dramatic anti-rat efforts, it also signaled a broader shift in public health approaches. The era of volunteer-run public health programs was ending, replaced by professional municipal services. The Boston Board of Health took over the work that the well-intentioned ladies had begun and implemented a more systematic approach to rodent control.

The Battle Continues

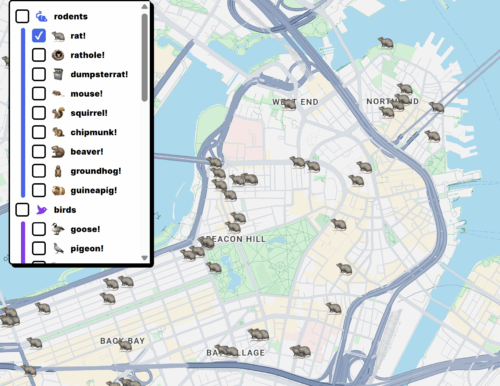

More than a century later, Boston continues to grapple with its rodent population. The city devotes significant resources to containing rats and established the Boston Rodent Action Plan (BRAP) in 2024. This coordinated, multi-agency initiative works to address what urban rodentologist Dr. Bobby Corrigan calls “a modern-day city conundrum.”

Today’s approach recognizes that human behavior significantly contributes to rat populations. The old infrastructure that once made the West End a haven for rats— old cobble or brick streets, intertwining alleyways, and aging sewer systems—continues to provide ideal conditions for rodents in older neighborhoods.

The Rat City Arts Festival in Allston-Brighton confronts the problem with Bostonian irreverence. The Festival organizes “rat safaris” where volunteers armed with flashlights search for rats while learning about mitigation strategies. It’s a far cry from the earnest ladies of 1917, but it represents the same community spirit that drove the original Rat Day.

Modern Boston has also learned from the West End’s experiences. The city’s current Boston Rodent Action Plan emphasizes that sustainable success requires addressing environmental root causes. Rather than relying on extermination efforts, they also emphasize proper garbage management and building maintenance. This approach might have served the Old West End as defective trash management was a key factor in the neighborhood’s rat problems.

The story of Boston’s 1917 Rat Day serves as both a charming historical curiosity and a reminder of the persistent challenges cities face. While the Women’s Municipal League may not have achieved their goal of a rat-free Boston, their efforts represented something valuable: a belief in civic engagement and the power of community action to address urban problems. Today, as Boston continues to battle its rodent population with professional expertise and modern technology, the spirit of those determined women lives on in neighborhoods across the city, where residents still come together to tackle the challenges of urban living, one rat at a time.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Boston Housing Authority, “West End Redevelopment Plan Declaration of Findings” 1957; Boston Women’s Municipal League Committees, Bulletin, Volumes 8-9, 1916-1917; Ray Cavanaugh, “When dead rodents enlivened Boston’s civic spirit.” Boston Globe, February 11, 2017; Census Bureau, “1920 Census: Fourteenth Census of the United States, State Compendium – Massachusetts”; Dr. Bobby Corrigan. “The Boston Rat Action Plan Final Report: Part II.” Prepared for the City of Boston Office of the Mayor, Michelle Wu, June 17, 2024; Hub History podcast, “Episode 72: Rat Day” ; Claudia Kelty & Stephen Edgell. “The Old West End of Boston” (unpublished manuscript excerpts); Jessica Ma “‘It’s definitely Rat City for a reason.’ A ‘rat safari’ in Allston sheds flashlight on rodent problem.” Boston Globe, August 18, 2025; MassLive.org. “Mass Moments – February 13, 1917: Boston holds first ‘Rat Day.'”; New England Historical Society. “Boston’s Rat Day of 1917.”; rats.boston, rat tracker; Chris Sweeney “Aw, Rats! Boston’s Rats Are in Charge. We Just Live Here.” Boston Magazine, February 20, 2018.