Destruction and Disappointment: The Legacy of Boston’s Central Artery

Boston’s Central Artery promised relief to the city’s traffic dilemma, but as with most major building projects of the mid-20th century, it brought demolition, displacement, and ultimately disappointment.

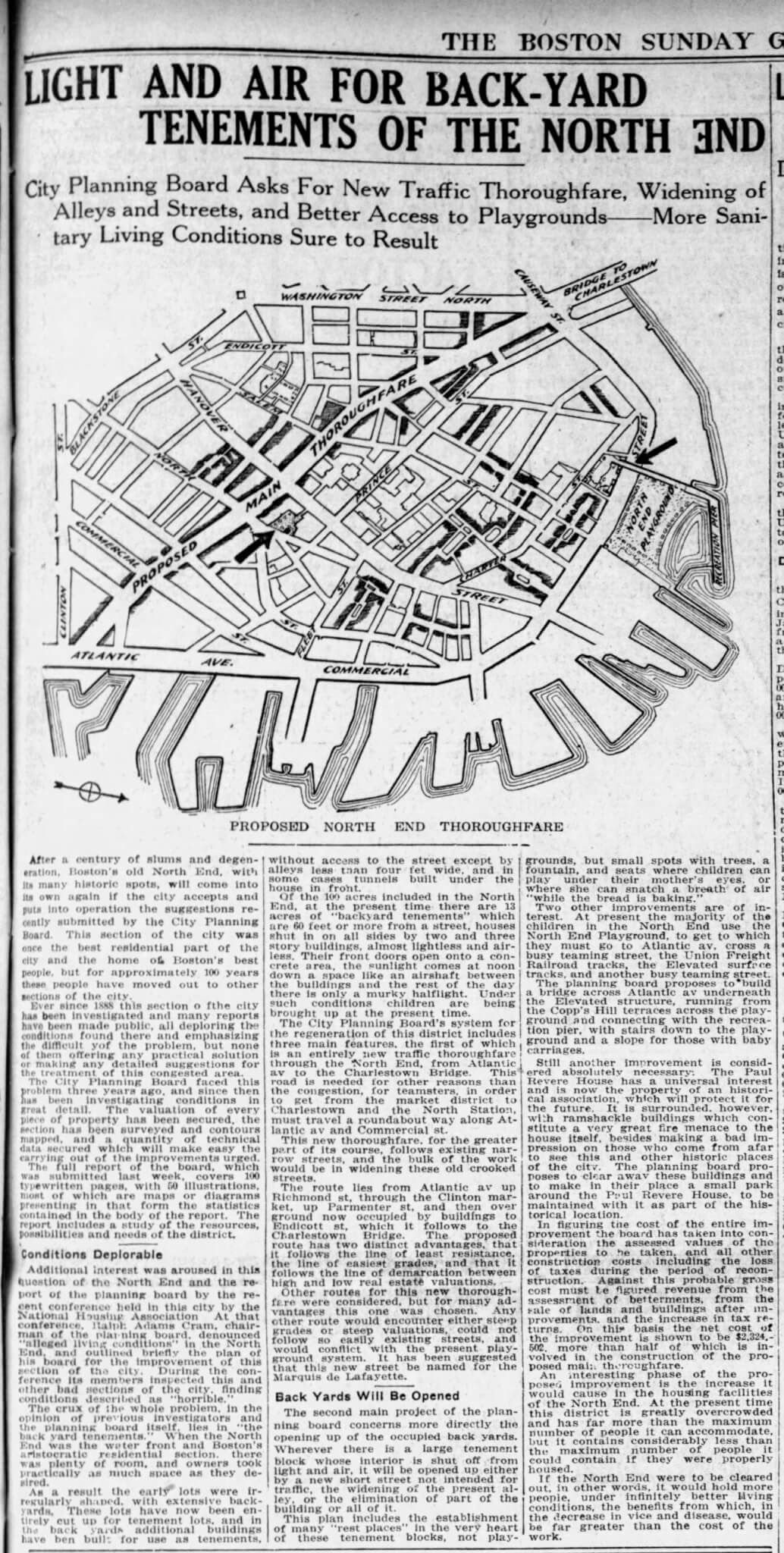

Less than 20 years after the first automobiles hit the dirt roads of Boston, traffic congestion had become a serious problem in Boston. So bad in fact, that as early as 1918 city officials suggested a plan for a north-south road to speed up traffic through downtown. Given central Boston’s location on a crowded peninsula, designing such a highway would never be an easy task. With little free space to work with, such a highway would have to go over, under or through existing buildings.

Experts made similar proposals in the 1920s and 30s, but political indecision, The Great Depression, and WWII contributed to delays for all major building projects in the city. After winning the mayoral election in 1949, Mayor John Hynes promised to build a New Boston. This program would include the infamous urban renewal projects in the South End and West End, a parking garage under Boston Common, and a planned highway to improve the city’s traffic woes. Known as the Central Artery (later the John F. Fitzgerald Highway after the former mayor) the project was spelled out in the Massachusetts Master Highway Plan for the Boston Metropolitan Area (1948).

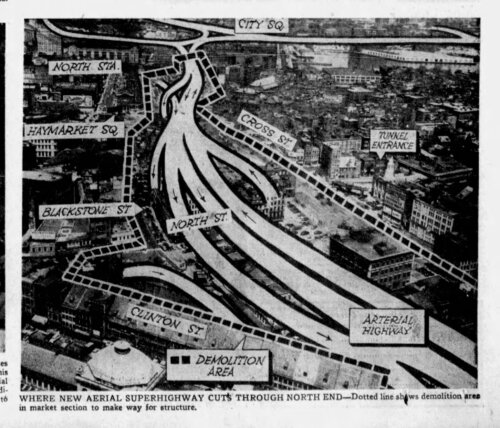

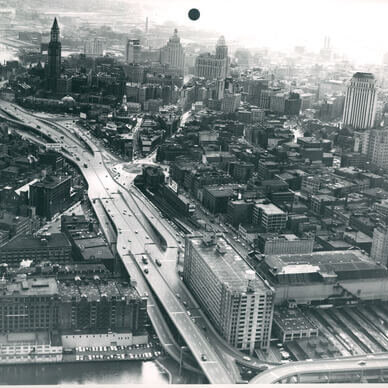

The new highway would run through the east side of Boston, connect to the Northern Artery in Somerville, cross the Charles River, and link up to the Southeast Expressway near Chinatown to the south. Its green-painted, steel superstructure would stand 30-50 feet above ground, consist of six lanes and over 20 on/off ramps, for a planned daily volume of 75,000 cars. The total cost for the combined projects was too high for Boston and surrounding areas, so the state of Massachusetts issued $450 million in bonds to finance the construction. Section one of the Fitzgerald Expressway that ran through the North End and West End cost $55 million. This is approximately $756 million in 2025 money.

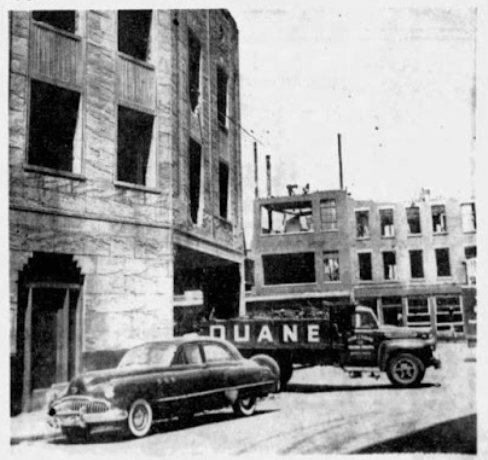

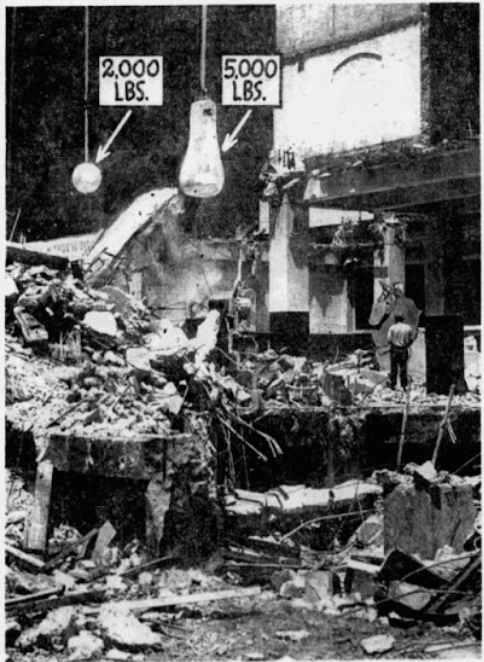

There was another cost, however, to be paid by residents and businesses of Boston standing in the path of the future Central Artery: buildings would have to be removed. One affected area was the northern half of the Bulfinch Triangle in the West End, and along North Washington Street in the North End. In the spring of 1951, seven years before the demolition of the core of the West End, workers began tearing down buildings on Beverly, Causeway, Endicott, Haverhill, and Traverse Streets. Ironically, the demolition project was led by the John J. Duane Company of Quincy, whose equipment would later be seen tearing through blocks of West End tenements in 1958. In this part of the project area alone, 346 buildings were demolished, displacing 100 families and scores of businesses.

The path of destruction also included Haymarket Square, where meat and produce sellers had been operating for centuries. There is little written record of protests from those in the North End and West End project area, but the 700 pushcart peddlers and meat businesses located in the soon to be cleared Haymarket put up a fight. They demanded relocation and protection for their losses. They appealed to local politicians who were able to win a five month delay in their eviction until the city could work out a plan. Eventually, in 1953, the meat and produce businesses were offered a space off Southampton Street in the South End. The largest, and most successful, protest against the Central Artery came from the residents of Chinatown. They forced the city to place the connector to the Southeast Expressway underground, preventing some of the demolition of the neighborhood.

The design of the original Central Artery and the difficulty of predicting future traffic flow brought about its ultimate demise with the Big Dig Project. By 1990 daily traffic volume had reached 200,000 (compared to the planned 75,000 in 1959). Traffic on the road was at a standstill for over ten hours per day; its accident rate was “four times the national average”; and it cut off major parts of the city from the waterfront and downtown. In addition to a failure in traffic flow and its original cost, the Central Artery displaced a total of 20,000 people and cost the city $20,000,000 (1952 dollars) in lost tax revenue from demolished property. The remedy for the Central Artery, an underground throughway, came with the $14 billion Big Dig project in the 1990s. In contrast to the high number of people displaced in the era of urban renewal, the Big Dig was committed to limiting the physical and human impact of the city.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Jaydie Halperin.

Sources: Robert J. Allison, A Short History of Boston. Beverly, Mass: Commonwealth Editions (2004). The Boston Globe, December 8, 1918 | March 09,1951 | April 04,1951 | January 30,1952 |February 10,1952 |March 14,1952 | May, 26,1952 | July, 05,1952 | March 25, 1953 | April 26, 1953 | March 07, 1954 | January, 07, 1954; Bostonroads.com ; Leo F. De Marsh, “John F. Fitzgerald Expressway Boston Central Artery”, Traffic Quarterly, April, 1956; Mass.gov.

1 Comment