Titus Sparrow: The Tennis Ace who Brought Courts Back to Boston

Renowned tennis player and Boston native, Titus Sparrow (1908-1974), recognized that a city owed its residents more than just roads and bridges. During a long career in which he taught hundreds of young tennis players, Sparrow advocated for public tennis courts for all neighborhoods. He encouraged community engagement and activism to make urban renewal project areas more than empty parking lots.

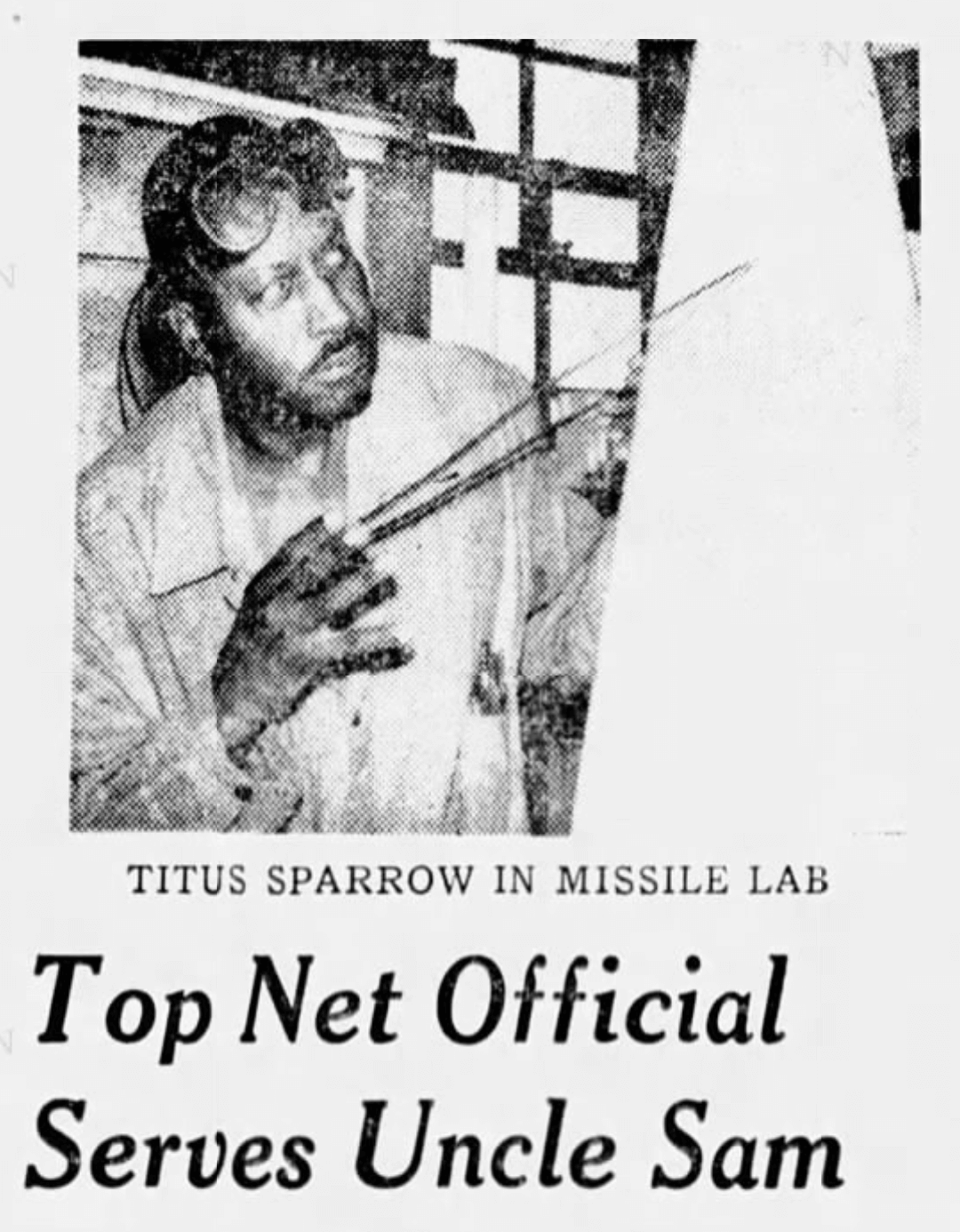

Titus Sparrow was born in Boston in 1908 and battled a difficult case of rickets at age 5, making him unable to walk. Thankfully, a successful surgery resolved the disease, and from that point forward, Sparrow started walking and running, and never stopped. Sparrow graduated from MIT, majoring in the design of special tools for electronics. He taught machine design in Europe and lived in Russia for 4 years in the 1930s as the nation was industrializing. There, he taught tool and die making and worked to lay out tennis courts for use by regular people. Prior to the Russian Revolution, only nobility played tennis.

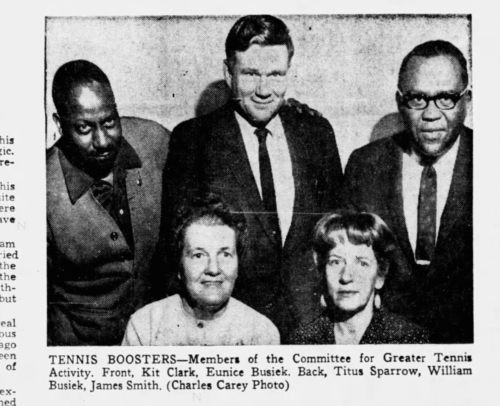

Upon his return to the United States, Sparrow was a leading tennis player throughout New England in the 1930s and 1940s. He was a tennis official of the Old Boston Tennis Club and the Roxbury Sportsmen. In 1956, Sparrow became the first African American Umpire for the US Tennis Association. He officiated at the Longwood Tennis Club in Brookline, the US Open in Forest Hills, and the Davis Cup. His numerous awards included Sport Magazine’s Award for Civic Achievement (1968), the New England Tennis Association’s New England Gardner Clase Bowl (1969) for exceptional contributions to the game, and the McGovern Award for outstanding tennis official (1971). The bangboard at Franklin Field was named in his honor in 1974, and Sparrow was inducted into the USTA New England Hall of Fame in 1993.

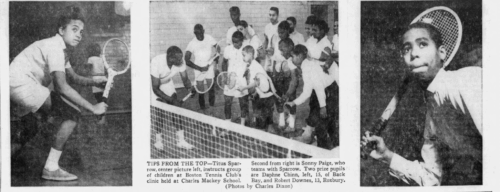

Sparrow’s enduring commitment to Boston was through tennis. He began tennis programs for children at Carter Field in Roxbury, and helped form the Sportsmen’s Tennis Club, which for decades, taught tennis to thousands of city children for free. Sparrow worked with the city, while battling the bureaucracy. In June 1968, Boston had only 25 usable tennis courts. This was a source of frustration since Franklin Field alone once had 32. Incredibly, you were expected to bring your own tennis nets! “What poor kid has a tennis net” Sparrow was reported to say at the time. At the same time that Carter Field deteriorated, the city chose to construct two courts in Boston Common, with lights for night play at an additional cost. These courts would serve a wealthier and whiter demographic while there were apparently no funds available for Roxbury, much to Sparrow’s chagrin. This unequal spending spoke to Boston’s unfortunate history on race.

It was in St. Botolph and South End where Titus Sparrow’s lifelong dedication to the community was most apparent. The St. Botolph section of Back Bay and the South End were drastically different from the present day. It was a grittier, more economically challenged area, often ignored by the city. The Penn Central railroad tracks divided the two communities instead of the Southwest Corridor Park and the ominous threat of the 12 lane South End Highway Bypass loomed large. Sparrow lived much of his life at 9 Durham Street, notable for the poem on his door: “Dry, rain, snow or sleet, before you enter, wipe your feet”. In the 1960s, Sparrow was a member of the St Botolph Citizens Committee and chaired its subcommittee on litter removal. He pressed his neighbors to dispose of litter properly, saying, “This poor black area gets no attention from the city”. He led by example, often cleaning the area himself. Sparrow also worked with the police to combat prostitution, rowdyism and street crime.

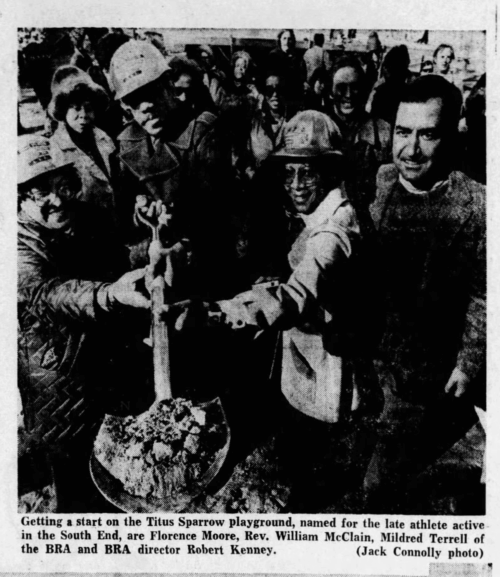

The legacy of Sparrow’s work to increase access to green space and tennis courts is preserved today in the form of Titus Sparrow Park. This park was built on the rubble of urban renewal. An urban renewal project in 1966 tore down 8 houses on both West Newton and West Rutland Streets, with the intention of creating public and elderly housing. Instead, for over 7 years, half the lot was empty, and used for illegal dumping. The other half was paved for Prudential Center parking. By the early 70’s, Sparrow, along with Durham Street neighbors Michael Joliffe and Ray Willingham, convinced the city to build a park instead. They worked with the four surrounding neighborhoods and the Union Methodist Church to build the park. Titus Sparrow passed away in 1974, before the park was completed. It was posthumously named for him in 1976.

Powered by an energetic group of volunteers, the Friends of Titus Sparrow Park, the park celebrated its grand reopening in November 2024 with more than 350 community members including Mayor Wu, Representative Moran and Councilor Flynn. The nearly year-long renovation by the Boston Parks Department included new, state-of-the-art playground equipment, updated sports courts, improved drainage, and lawn rehabilitation. Titus Sparrow Park is on course to be the best used and most beautiful park in Boston, and most importantly, a fitting tribute to its namesake.

Article by Irwin T. Levy, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Alison Barnet, Once Upon A Neighborhood: A Timeline and Anecdotal History of The South End of Boston, (Boston, 2019); The Boston Globe December 9, 1962, February 17, 1964, October 15, 1966, January 29, 1967, November 17, 1974; The Friends of Titus Sparrow Park; Gard Hartmann, ed, South Enders Remember, (Boston: Local History Press, 2023); Robert Hayden, African Americans in Boston: 350 Years, (Boston : Trustees of the Public Library of the City of Boston, 1991).