The Signscape of Scollay Square

Scollay Square, Boston’s port-side entertainment center, was full of flashing marquees. Directional signs on theatres, peepshows, and taverns helped people find their way through the maze of cobbled streets and guided crowds to transportation or fun. Though Scollay Square was destroyed by urban renewal, the vibrant electric atmosphere has been preserved in a few surviving relics and memories.

The Paramount Theatre’s vertical sign still glows on Washington Street in Boston, a façade of chrome, glass, and neon. It evokes memories from a time long passed. Arthur H. Bowditch designed the marquee in 1932 for the Paramount chain and it was later redeveloped by Emerson College. The theater’s restored marquee and tall sign remain among the most recognizable features of Boston’s art deco landscape. While most of the original interiors are gone, Emerson’s 2010 renovation reinstated the iconic sign and preserved the façade.

Following Washington Street northward from the Paramount once led towards the electric world of Boston’s portside entertainment capital. Sailors, showgirls, and shopkeepers moved through a corridor of taverns, theaters, tattoo parlors, and tenements. The path of glowing signs culminated in Scollay Square. The Paramount’s radiance is one of the few remaining relics of this once vibrant area.

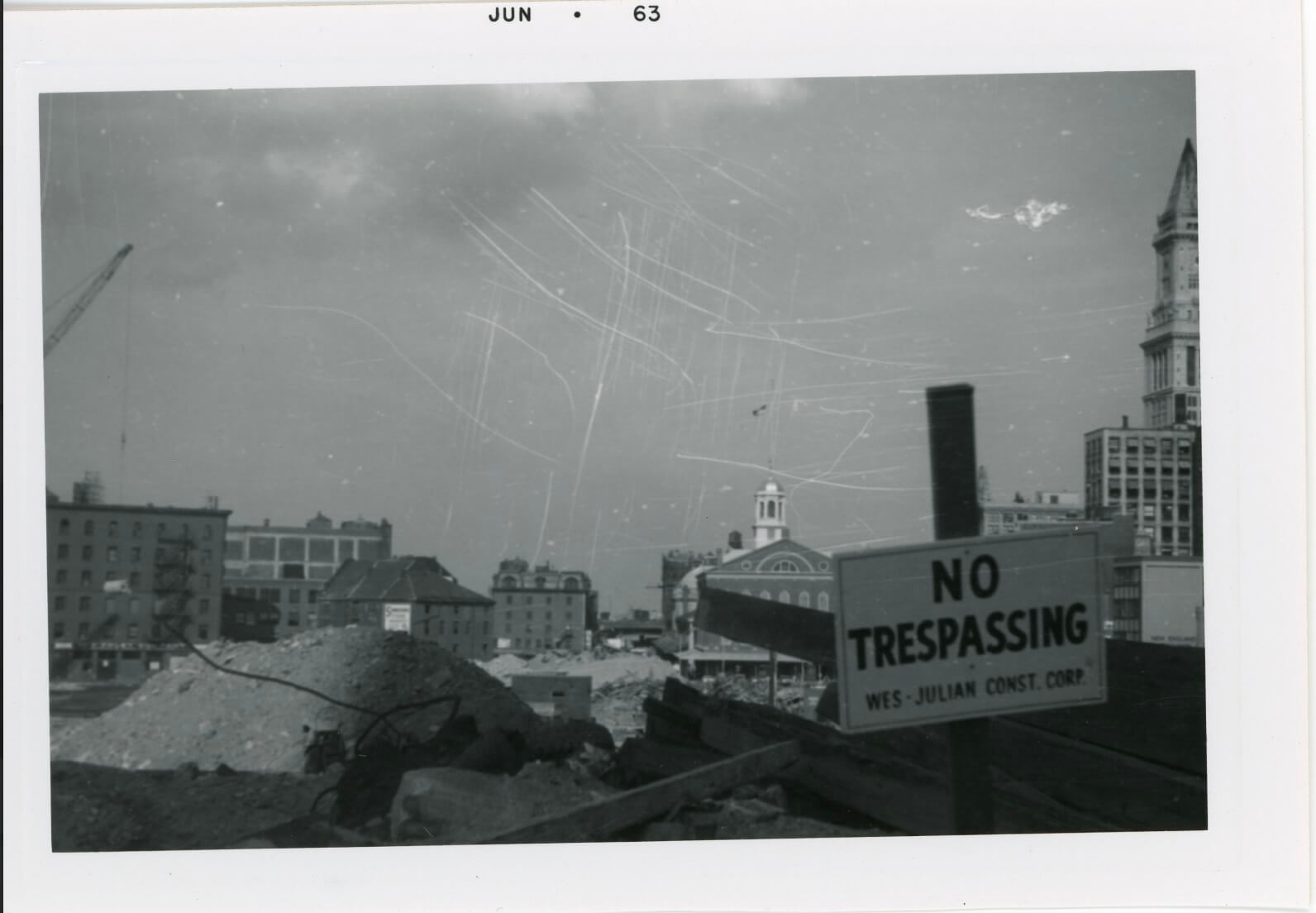

A large urban renewal project in the 1960s was the demise of Scollay Square and the art deco signs that used to entice patrons inside. The open concrete of City Hall Plaza replaced the intimate density of Scollay Square’s cobbled streets. Federal money and eminent domain helped the city acquire almost all Scollay Square properties by 1962. Using urban renewal funds, Boston built its new City Hall, opened in 1968, on what was once Scollay Square.

The signs in Scollay Square did not just communicate basic information about when and where performances or activities took place. They glowed with feelings. Marquees and train directories created a sense of urgency by advertising This Hour, Tonight, and Continuous Performance. They also beckoned their potential patrons closer by guiding them Here, Around the Corner, and Upstairs. The Rialto Theatre’s marquee proclaimed it was “Open all Night,” embodying Scollay Square’s nonstop energy. These visual cues allowed patrons to recognize who they could look at and who could be looking at them. They organized the square into a space where people knew where to go for what they desired and could easily circulate.

Scollay Square was dense with invitations. There were theatre shows to attend, stacked storefronts to shop in, and transit crowds to navigate. The marquees cluttering the district animated its streets. Theater façades shouted in neon script and light bulbs. They formed a flickering advertisement for vaudeville and burlesque. Tattoo parlors for naval clientele filled the area. Their storefronts were crowded with painted signage showing the talent of the tattoo artists within. Even Scollay Square station, opened in 1898 as one of the earliest subway stations in the city, had signs. Tile mosaics reading “Scollay Under” announced passengers’ arrival into the hub of signs. These mosaics, uncovered during the 2014 renovation, can be seen today in Government Center Station.

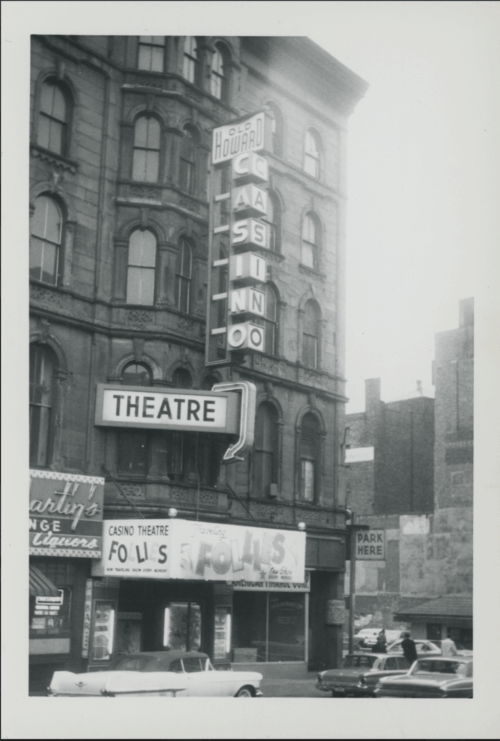

From the nineteenth century, Scollay Square pulsed with vaudeville theatres. The Howard Athenaeum, opened in 1846 and for decades hosted opera, drama, and variety. A performance of Lydia Thompson’s British Blondes in 1869 was the start of burlesque at the Old Howard. Later performers included Gypsy Rose Lee, Fanny Brice, Ann Corio, and Sophie Tucker. Nearby stood the Olympia Theatre, the Theatre Comique, and Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum. Each erected signs and flashing lights to show customers what excitements they could expect inside.

As the twentieth century progressed, the Old Howard shifted from “clean” variety shows to burlesque. By the 1920s, chorus girls, strip-teases, and midnight shows dominated the stage. In the lanes around the theatre, bars and taverns flourished. At a tavern called Crawford House students, sailors, local barflies, and even, shockingly, young ladies, could buy beer for fifty cents a bottle and visit with strippers. But the Old Howard and its contemporaries wouldn’t survive forever. The vice squad brought charges of indecency and the spectre of urban renewal led to the entire square disappearing by the mid 1960s. Nearly the entire neighborhood was razed to make way for today’s Government Center.

After the demolition of Scollay Square, many burlesque houses, bars, and adult businesses relocated southward to an area named the Combat Zone. The Combat Zone was active from the 1960s through the 1980s. It was primarily around lower Washington Street, Boylston Street, and LaGrange Street, just south of Boston Common and the Theatre District. In this new location, the same style of neon signage, sex work, peep shows, theaters, and adult entertainment reappeared. While city officials tolerated the Combat Zone, residents of neighboring Chinatown pushed back against the area’s seedy nightlife. Eventually, the last vestiges of Scollay Square signs were taken down as the Combat Zone shrunk and then disappeared.

Even though the buildings of Scollay Square are gone, imagination can bring back the memories of the elaborate signs that once filled the streets. Each marquee, billboard, and painted façade formed a living diagram of potential paths through the neighborhood. Light and language became a map to the square and each individual experience. As urban theorist Guy Debord described, there is a sense of magic to reading and following the visual language of a city. He called it dérive: the act of wandering through a city guided not by efficiency but by emotion, curiosity, and randomness. This gave pedestrians the ability to enter theatres, taverns, and have chance encounters at their own pace. As a result, the city felt alive, and full of promise. In mid-twentieth century Boston, and especially Scollay Square, the overlapping glow of neon and hand-lettered boards created a geography guided by emotion rather than design. The signage did not simply advertise. It choreographed movement and directed people to unknown possibilities.

Article by Helen Eshetu, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Emily Anderson “What do these signs mean at the new Government Center T stop?” (Boston.com, March 22, 2016); City of Boston “Report of the Boston Landmarks Commission on the potential designation of the Paramount Theatre as a Landmark under Chapter 772 of the Acts of 1975”; Queenie Chen, “The Howard Athenaeum” (The West End Museum, August 15, 2023); Alejandra Dean “Notes from the Archives: Urban Renewal and Government Center”, (City of Boston, July 17, 2017); Guy Debord, “Theory of the Dérive,” Internationale Situationniste #2, 1958; Adam Gaffin, “There was more to Scollay Square than burlesque,” (Universal Hub, April 6, 2025); Erica Noonan, “Boston residents fear return of Combat Zone,” (The Daily Courier, December 6, 1998); Stephan O. Saxe, “Saturday Night in Scollay Square: Burlies, Girlies, Bars, and Bums,” (The Harvard Crimson, September 12, 1951); Adam Vaccaro, “At revamped Government Center station, echoes of a burlesque past” (Boston.com, March 18, 2016).