The Omnibus: Boston’s First Horse-Powered Public Transit System

Boston established its first form of urban public transit—a large horse-drawn carriage known as the omnibus – in 1833. The omnibus was an early step in the creation of Boston’s public transportation system. With lines crossing the West End, and a hub on Brattle Street, the omnibus promoted city-wide connectivity. As technology improved, however, horsepower was slowly phased out.

In 1833, Boston established its first form of urban public transit. It was not a train or a streetcar, but rather an oft-overlooked form of transit known as the “omnibus.” This new way to traverse the growing city met a demand for increased connectivity in Boston. Yet omnibuses were uncomfortable for riders, chaotic, and quickly supplanted by upgraded forms of transit. However, they played a critical role in the development of Boston’s public transportation system.

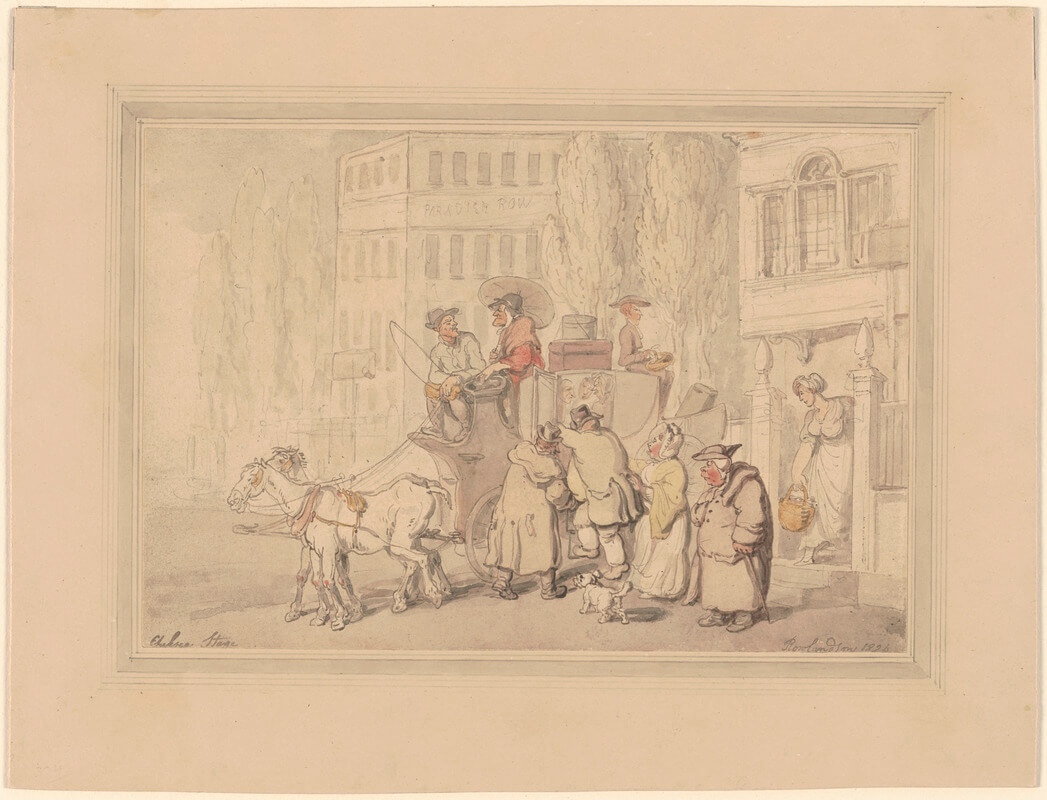

Before the early 19th century, a city’s size was generally limited to the distance one could comfortably walk (about a half mile). With the industrial revolution, new demand for factory workers led to a swelling population. This caused the city to spread out to accommodate more people who needed transportation to get to work. Moreover, the growing middle class sought new forms of transportation. They could not afford the private carriages of the wealthy, but did not always want to walk. Stage coaches were an early attempt to meet this need. They traveled mostly between cities along fixed routes much like modern coach buses.

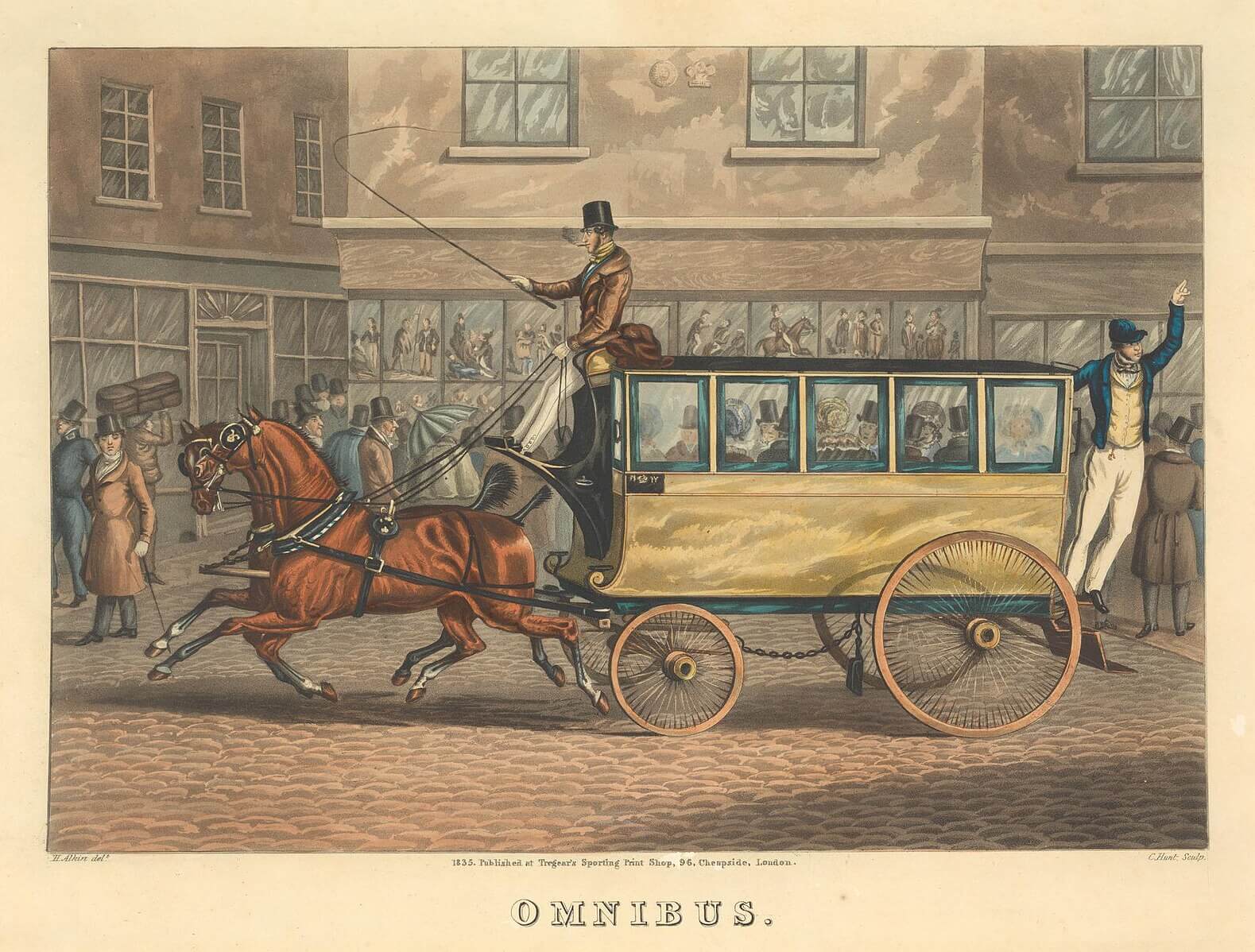

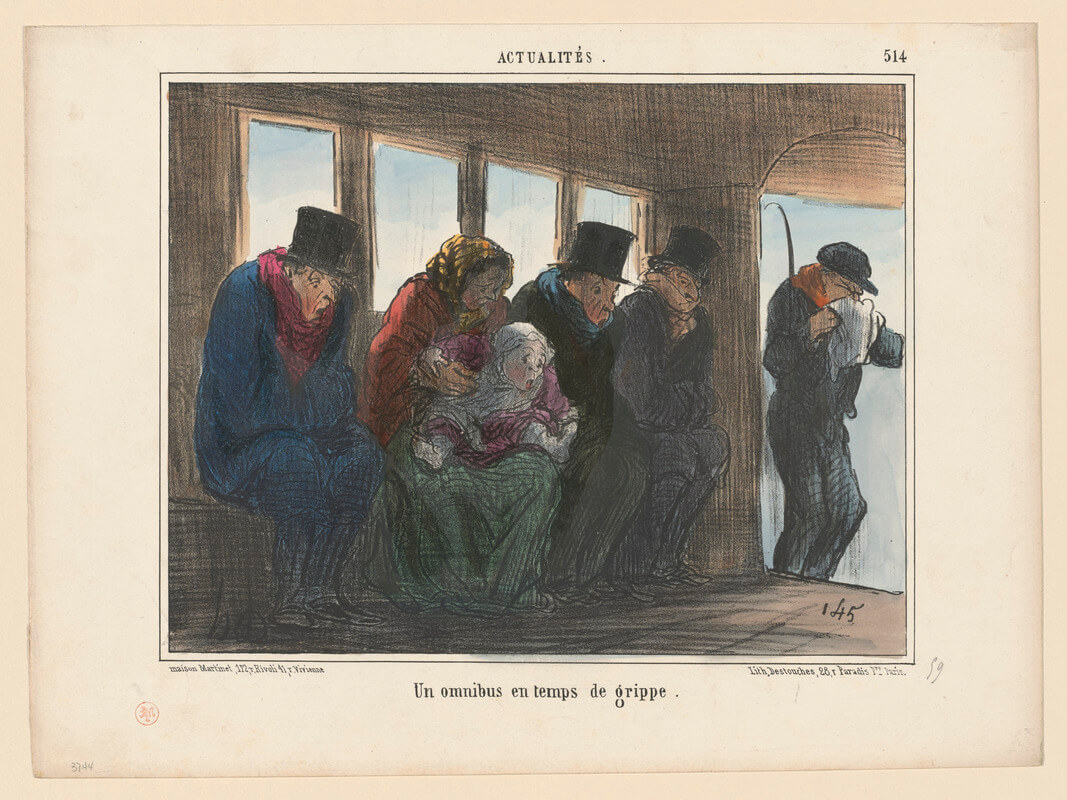

In 1831, New York City introduced a European invention known as the omnibus. The name came from a Latin word meaning “for everybody” and is the root word of the modern term “bus”. The omnibus was a large horse-drawn coach, enclosed on all sides. It was typically pulled by two to four horses, with a driver positioned at the front. Inside the omnibus were two benches sitting up to 8 passengers facing one another. Unlike coaches, which loaded from the sides, an omnibus had one door at the back of the carriage from which passengers could enter and exit. For omnibus passengers, the ride was far from pleasant. Omnibuses sped along city streets, jostling and tossing their passengers with every bump in the road. Straw lining the floors of the omnibus became damp, housed fleas, and spread diseases.

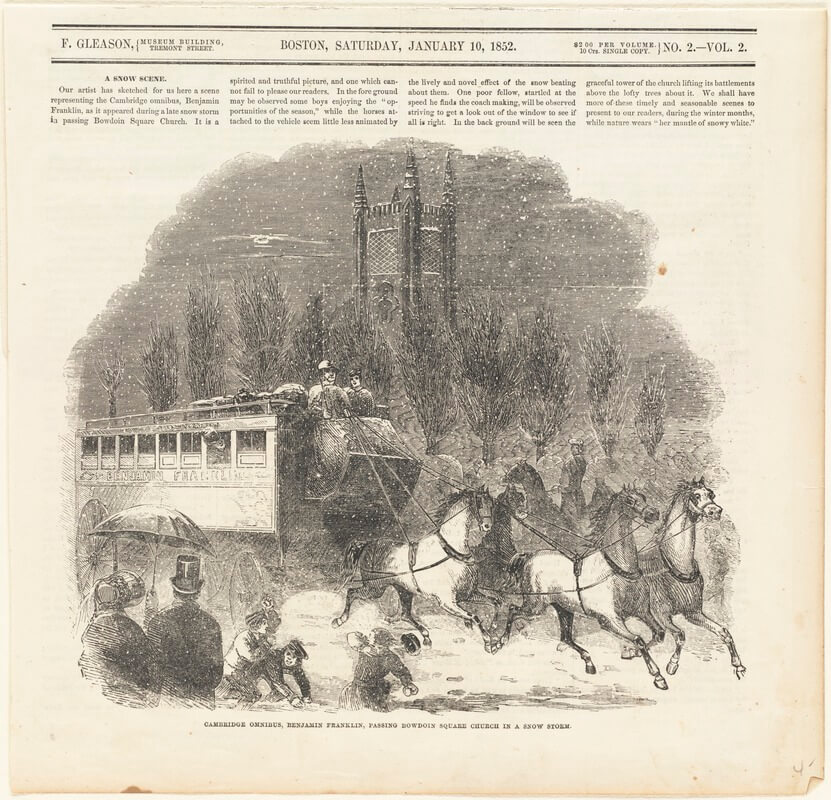

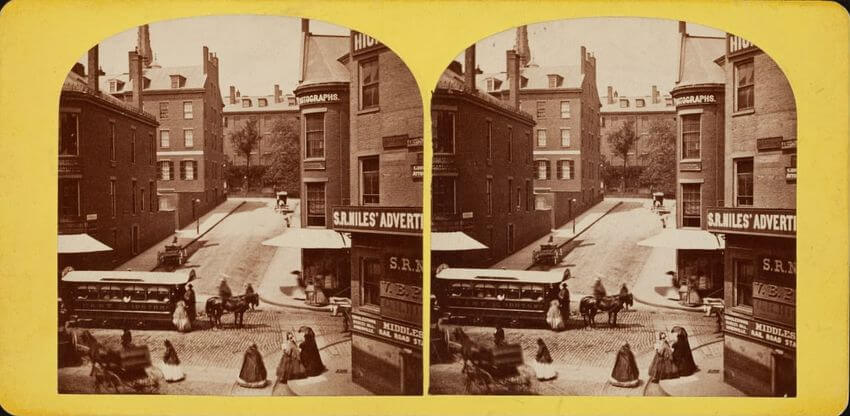

Boston was quick to adopt the omnibus in the early 1830s, shortly after New York City. The first Boston line connected the Norfolk House in Roxbury to the Winnisimmet ferry, which ran from the North End to Chelsea. Within around a decade, there were 28 lines within Boston. Among these, three particularly popular routes crossed through the West End. These routes connected Boston with Cambridge, East Cambridge, and Charlestown. The Cambridge line originated on Brattle Street in what became Government Center.

The omnibus industry in Boston was unregulated at first. Independent services, often a one-man and a few-horse operation, ran many lines. Omnibuses would race to pick up passengers, endangering riders and pedestrians alike. The city fined drivers for “furious driving”, an early speeding ticket. Boston area newspapers recounted frequent injuries and overturned carriages. There were also conflicts between operators over stops. The omnibus needed guard rails!

Responding to these challenges and regulating the service laid the groundwork for the modern public transportation system. In 1838, the Boston Board of Alderman established official omnibus stops. On Brattle Street, for example, there would be a stop for the Cambridge, East Cambridge, and Charlestown lines. They also declared that omnibuses could not park at stands for more than 20 minutes. The regulation of routes and stops would become an important feature of later forms of public transit.

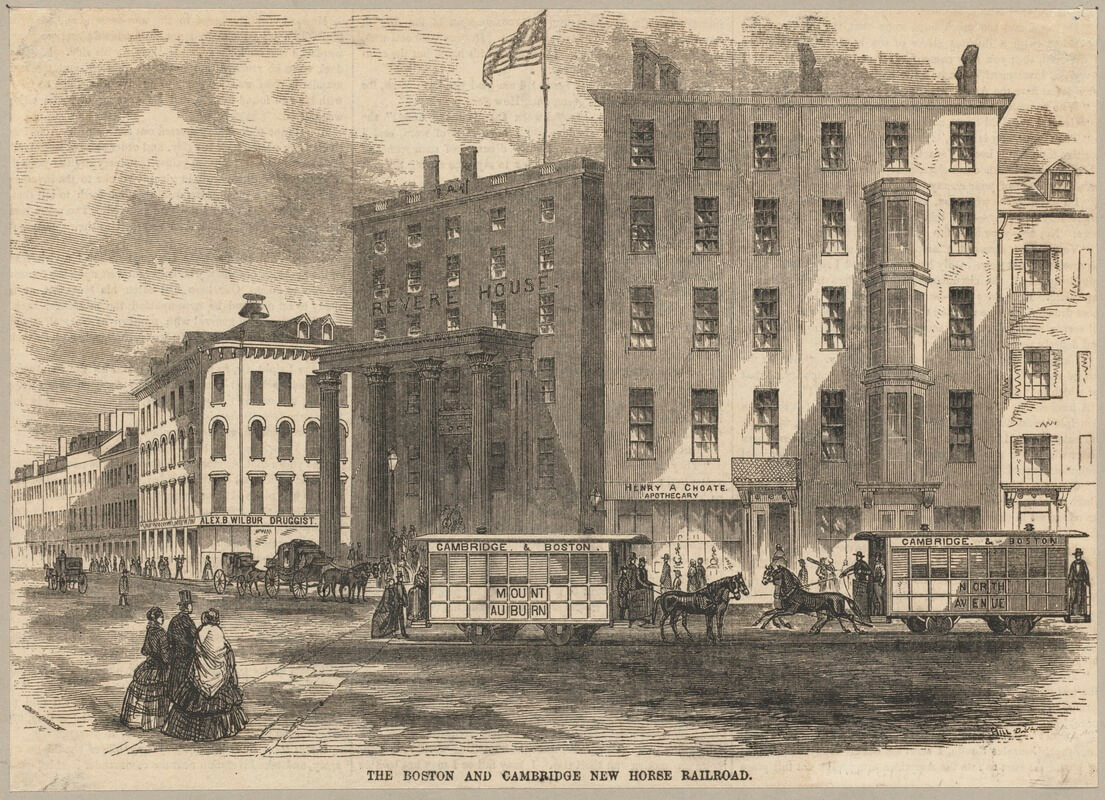

Even if riders now knew when and where an omnibus would arrive, the system was far from perfect. Rides were uncomfortable and increasingly crowded. This led to the development of horse-drawn streetcars. Also known as horsecars, these vehicles traveled on tracks laid down into the street rather than wheels like the omnibus. They were a predecessor to the electrified trolley, but were still pulled by horses. As a result of the smoother surface of the tracks, they were far more efficient and comfortable. The trolley could even carry more people with fewer horses. The technology was a hit. Many streetcar companies purchased and retrofitted omnibus equipment. Streetcar routes even ran along omnibus routes. The first horse streetcar route through the West End in 1856 followed a route nearly identical to the original omnibus Cambridge Line route.

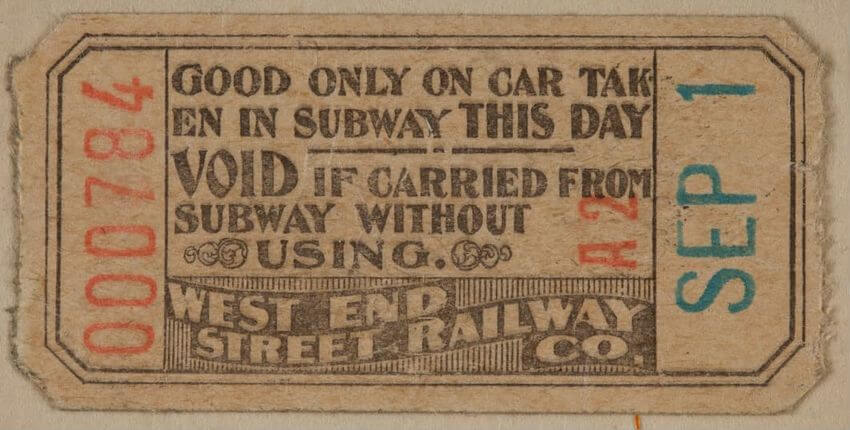

The transition to horsecars demanded larger amounts of initial capital than omnibuses. Besides horses and carts, prospective entrepreneurs now needed to install tracks. The days of independent operators ended quickly. By the 1880s, the West End Street Railway Company, founded by Henry Whitney, had consolidated much of the transit system for the city.

The arrival of the streetcar was much heralded throughout the city. A Cambridge Chronicle reporter who tested out the West End to Cambridge route wrote that the ride was so preferable that those who still had to ride the omnibus “deserve the commiseration of the friends of humanity.” But it was not a smooth transition for all as some omnibus drivers were pushed out of business. One group of exasperated West End omnibus drivers declared that they would be taking their services elsewhere and boarding a ship out of the state, or maybe the country! The omnibus drivers would go where they were appreciated.

The last omnibus service in Boston ended in 1898. By then, horsecars, electric railways, and the brand-new subway had become the preferred modes of transit.

Article by Beatrice Ferguson, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Source: Cambridge Public Library, Cambridge Chronicle, March 24, 1906; Gale Primary Sources – 19th Century Newspapers, Boston Daily Advertiser, September, 3 1855; Thomas J. Humphrey, Hourly Coaches, Omnibuses, and Horse Railroads: A History of Horse-Drawn Transit in Massachusetts, (Np., 2023); MBTA “The History of the T”; The West End Museum, “From Stagecoach to Subway: The West End Street Railway”, exhibit; Stephen Winick, “The Legend of Monsieur Omnès”, February 12, 2020, Library of Congress.