South Enders vs. The B.R.A.: Urban Renewal in Boston’s South End

In post-war Boston, city officials razed several low-income neighborhoods for urban renewal. Among those neighborhoods was the South End, a low-income yet culturally rich area. The story of community resistance to urban renewal in the South End included small victories. But the South End was fundamentally shaped by large-scale displacement and gentrification. Top-down urban planning and slum clearance tore the community apart.

Setting the Stage: Urban Renewal in Boston

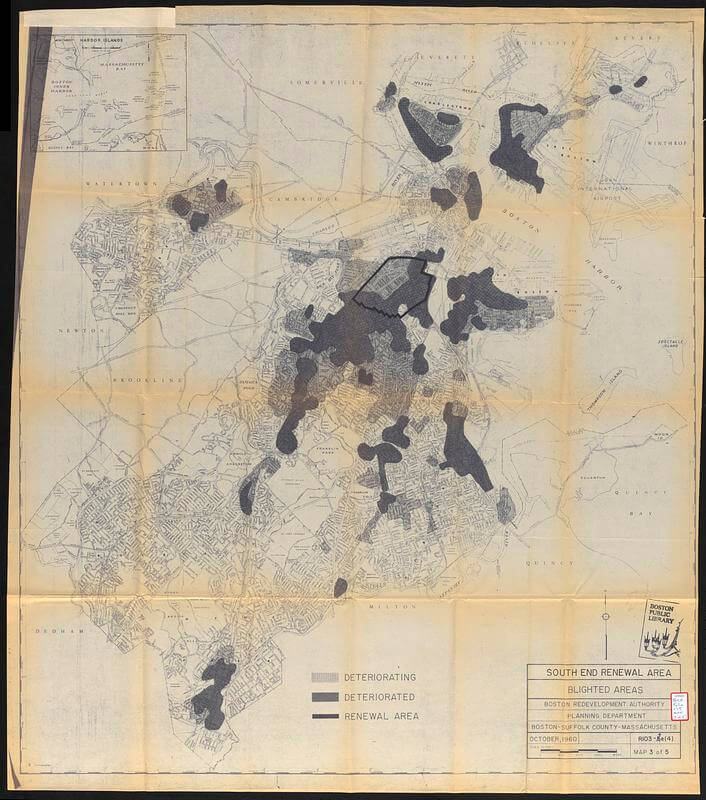

When city officials looked at the South End of Boston after World War II, they saw a slum. They characterized the South End as blighted, deteriorating, impoverished, and congested. Using new powers granted to them by the Housing Act of 1949, Boston authorities targeted low-income neighborhoods for urban renewal, also known as slum clearance. The City wanted to promote urban investment, lure suburbanites back to the city center, and increase Boston’s tax base. At the time, officials promised a New Boston that would reverse the trend of suburbanization and improve the city.

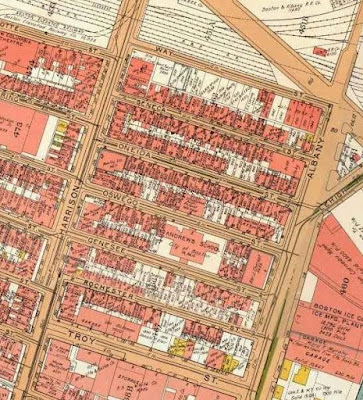

Despite City Hall’s negative attitude toward the South End, those that grew up and lived there thought differently. The neighborhood’s low rents were a haven for the working class and immigrants who could not otherwise afford to live in Boston Proper. One former resident of the New York Streets area of the South End described the neighborhood as an urban village. There, children could play games on the sidewalks and in the streets. Residents socialized with one another on their stoops. Shoppers purchased diverse foods and fresh produce in locally owned storefronts at affordable prices. Though often poor, former residents considered their upbringing rich and fulfilling in other ways. The authorities, on the other hand, only saw a “squalid” neighborhood that was not fit to live in. The bulldozers were soon to come.

Urban renewal in Boston first began in the 1950s with the destruction of the New York Streets of the South End, a diverse neighborhood with a large Christian Lebanese population. In 1955, the City had taken control of the neighborhood, and residents began receiving notices to vacate their homes that had been taken by eminent domain. By 1957, the new Boston Herald building, a light industrial area, and a highway replaced the homes of over 1,000 residents. Many from the New York Streets had to relocate to areas far from the South End and their old neighbors. This severed their tight knit community and destroyed important social connections.

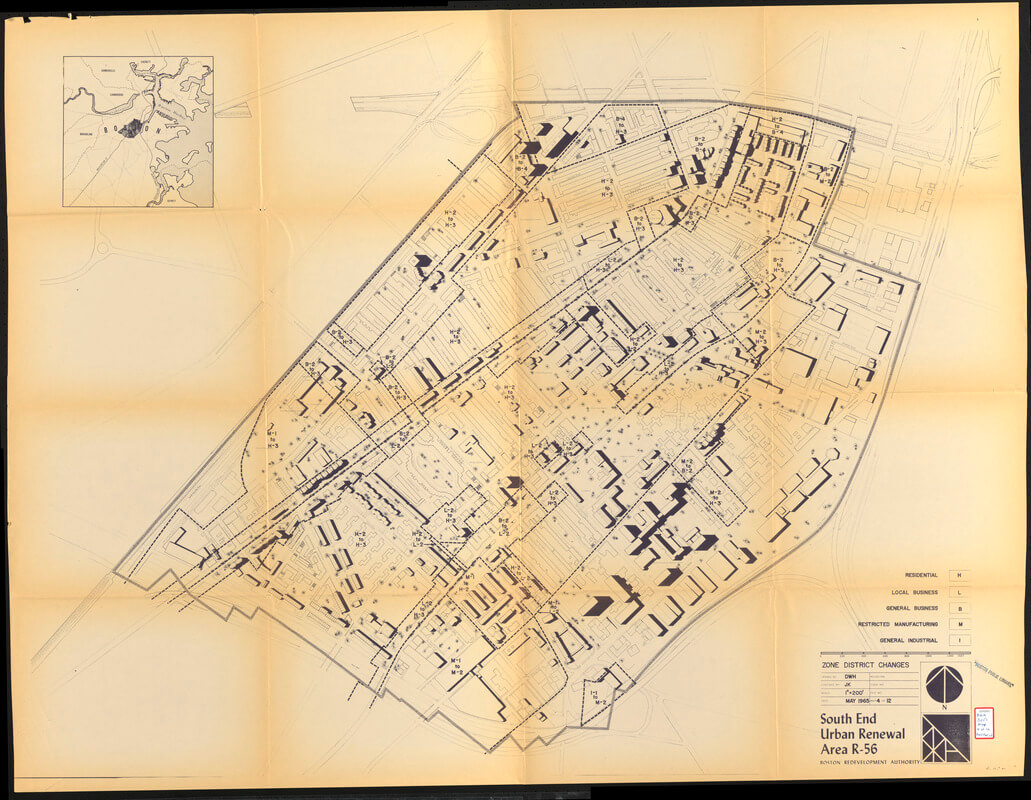

After this first wave of urban renewal in the South End, things quieted down. The Boston Redevelopment Authority was busy for a few years with the massive West End project. But they were not done with the South End. In 1964, the BRA published its South End Urban Renewal Plan, which laid out its objectives and proposed redevelopment areas. The plan’s goals were to promote public and private development and investment. Notably they listed this priority first. The BRA also wanted to increase the City’s tax base and change the way land was used in the South End neighborhood. The final goal was to promote the health and sanitation of residents. A combination of clearance, redevelopment activities, and rehabilitation would bring their plan to fruition.

Community Response

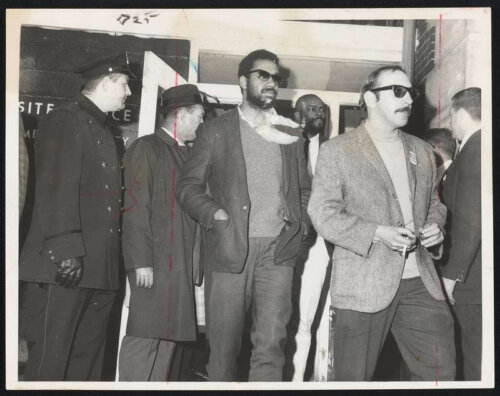

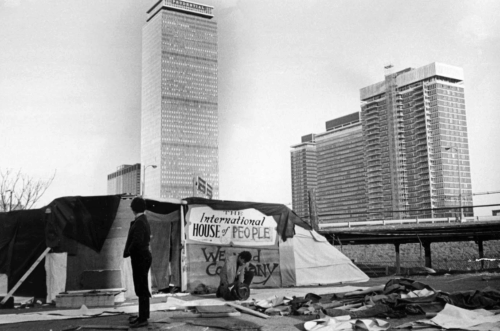

When urban renewal returned to the South End, many came together to organize and advocate for themselves. On April 25, 1968, members of the Community Assembly for a Unified South End (CAUSE) staged a sit in. Activist Mel King and members of the community occupied the BRA field office in an old fire house on Warren Ave. They demanded an end to the displacement of South End residents and more affordable housing. Protesters left in the evening, but they were not finished. The next day, the protesters occupied razed land used as a parking lot for suburban commuters. The tense stand off culminated in a commuter driving his car through the activists, forcing police to clear the lot. Undeterred, the protesters returned the next day and created a car-free “tent city.” After three days, police again cleared the lot, and CAUSE shifted its attention elsewhere.

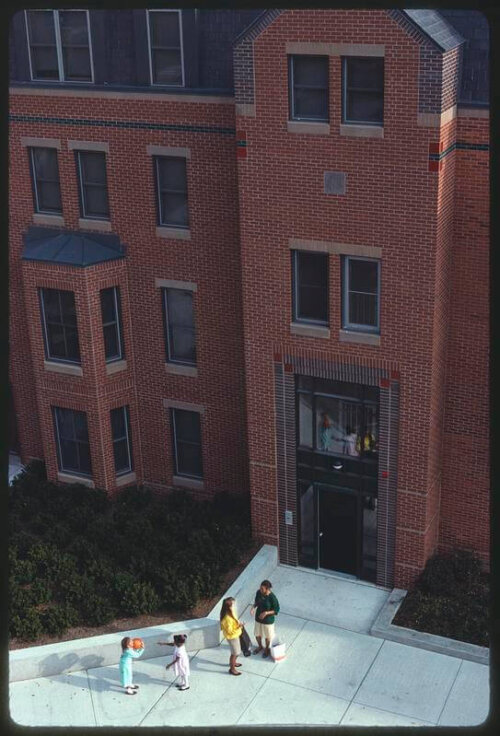

The protest successfully stalled any redevelopment of the lot by the BRA until it produced a plan that was acceptable to the community. King and other activists helped lobby for a housing-first solution and secured funding through the Greater Boston Community Development Corporation. Twenty years later, the site became home to “Tent City,” a mixed-income housing development. Working-class individuals and families and even some formerly-displaced South End residents were among the first occupants of the development. Today Tent City residents remain dedicated to preserving their mixed-income and diverse community.

Perhaps the most successful example of South End community action was its the Villa Victoria housing development. In 1967, the BRA attempted to tear down the neighborhood known as “Skid Row” and replace it with luxury housing. In response, Puerto Rican residents of the South End organized the Emergency Tenant’s Council (ETC). They gained the right to redevelop the land themselves and Villa Victoria was the result. It consists of several hundred units of affordable housing, gardens, and mini “town squares” modeled after town squares in Puerto Rico. The housing development is still a center of Latino life in the South End.

Aftermath and Legacy of South End Urban Renewal

The changes to the neighborhood mostly benefitted the neighborhood’s new upper-middle class residents. It was not improved for the people who used to call it home. Today, the South End is associated with luxury brownstone condominiums and a heavily gentrified neighborhood. In contrast to its pre-urban renewal immigrant and low income population, the neighborhood is now significantly wealthier and less foreign-born than the city as a whole. It also features rents that are higher than the city average. Present-day demographics, altered by decades of redevelopment and later gentrification, are a complete reversal from before urban renewal.

The City constructed housing units at a sluggish pace compared to the speed at which they destroyed them during urban renewal. Those it did build in the South End, such as Cathedral Housing (1949) and the Castle Square Project (1960s), replaced entire blocks of historically significant, Victorian-era brownstones with multi-family housing units. Mixed income units were built on the neighborhood’s periphery. In 1979, only 2559 housing units had been constructed, to replace the approximately 7000 units lost.

The BRA never acknowledged those displaced indirectly by South End urban renewal, especially the residents who could not afford rising rents, and were thus priced out of the neighborhood. Though the neighborhood fought to protect itself, the South End changed dramatically over the middle of the 20th century. For those displaced by urban renewal in the South End, the old neighborhood survives mostly in memory.

Article by Nick LaCascia, edited by Jaydie Halperin and Bob Potenza

Sources: Boston Planning and Development Agency, “South End Urban Renewal Area Map”, (Boston City Archives); Boston Preservation Alliance, “Tiny Story: Tent City”, (Boston Preservation Alliance, February 11, 2025); Boston Redevelopment Authority, “South End Urban Renewal Plan” (Boston City Archives, 1964); Adam Gaffin, “South End Gentrification, then and now”, (Universal Hub, November 30, 2023); Veer Mudambi, Yuan Tian & Abhishek Majumdar, “South End: Where Have all the Activists Gone?” (The Scope, December 7, 2018); South End Historical Society, “South End History Part III: Urban Renewal”, April 8, 2012; Amir Tadmor, “Victory Village: The Story of the South End’s Villa Victoria” (The West End Museum, March 11, 2025).