The Thriving Jewish Marketplace of Boston's Old West End Part Two: Deli Meats to Kosher Eats

This article is the third part of a series exploring Jewish life in the Old West End. This second part in our business series describes the many options for West Enders to purchase Jewish foods. Bakeries, delis, kosher butchers, and specialty stores served their community by selling at affordable prices and acting as community gathering places. Many proprietors also gave back to the West End in generosity and leadership.

The Jewish urban village of the Old West End had many iconic people and places that defined the character of the neighborhood. Small, family-owned businesses lined the streets and made outsized impacts on the community. From kosher butchers to liquor stores, affordable prices and involved owners contributed to the bustling local marketplace.

The Delicatessens: Community Gathering Places

One of the most iconic establishments in the West End sat at the corner of North Russell and Parkman Streets. Klayman’s Delicatessen was owned by Walter and Rose Klayman. The delicatessen became famous for its hot pastrami, and cream bagels. Its corned beef sandwiches were served on warm rye bread from Kravitz Bakery. The family ran this legendary neighborhood hub from the 1920s until the West End’s demolition in 1958.

Frank Lavine, who lived on Parkman Street, remembered Klayman’s as “a place that you stopped at least once a day. It was the corner that we went to show off our Halloween costumes”. He described it as “the hub of the hub of the universe; everyone hung out there. Rich, poor, smart, dumb, young, old, wise guy or working stiff, no matter your religion or nationality, this was the place.”

Meals were very affordable. Baloney was a nickel, the end of the bread cost 2¢, and salad or cole slaw were only 3¢. The establishment had the only telephone in the area, making it a vital communications center. Walter Klayman became legendary for his generosity. Former residents recalled that “no one ever left his place hungry if they didn’t have money to pay.”

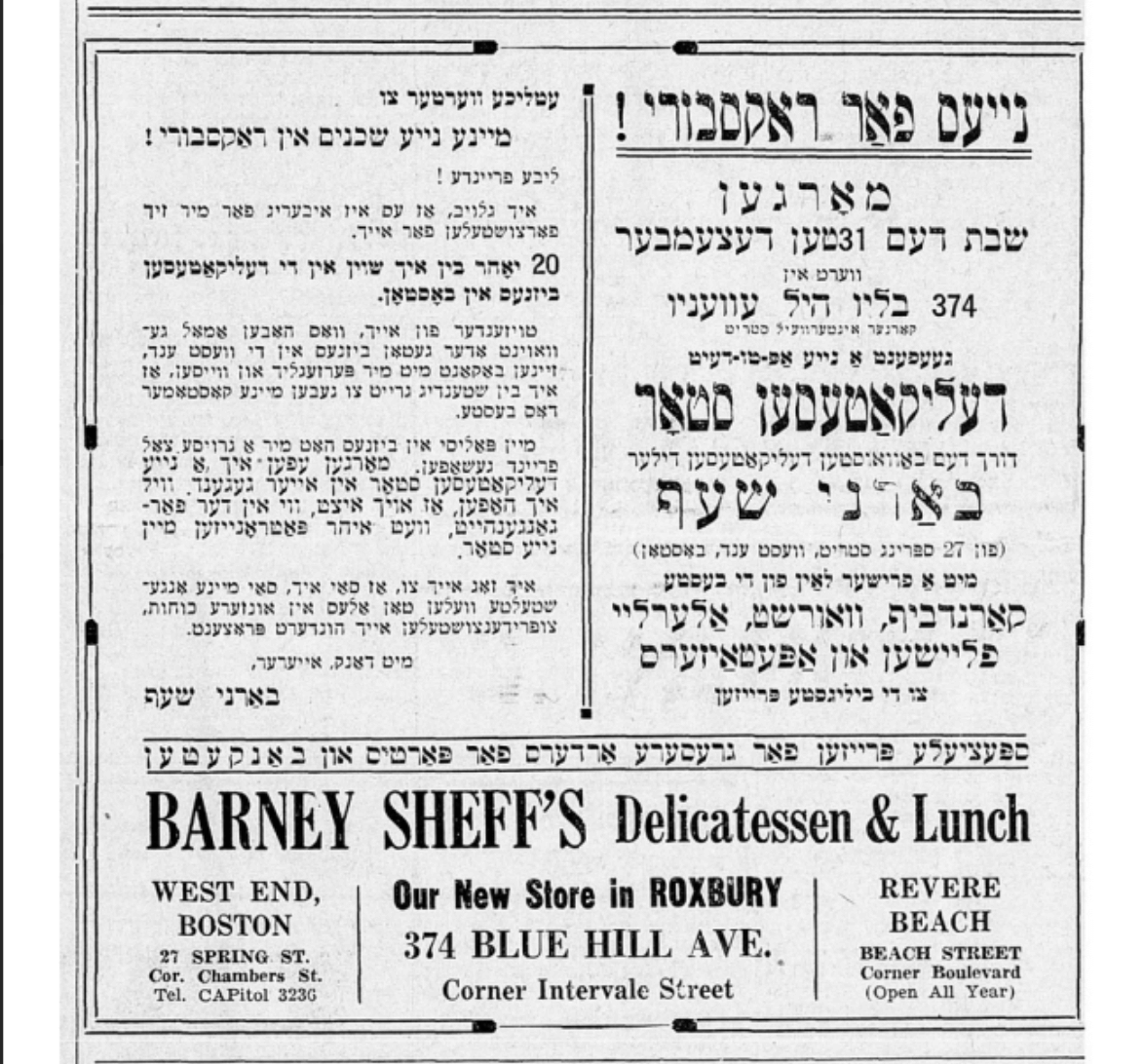

Barney Sheff’s Delicatessen, situated at the corner of Spring and Chambers Streets, rivaled Klayman’s in both reputation and community significance. Founded by Barney Sheff and his wife Ida, they worked side by side for 40 years building their business. Former Speaker of the House Tip O’Neill remarked, “The families and friends were always at Barney Sheff’s.” Barney Sheff’s success in the West End sprouted several locations throughout Greater Boston. Barney Sheff’s could be found in Dorchester, Roxbury, Revere, and Brookline.

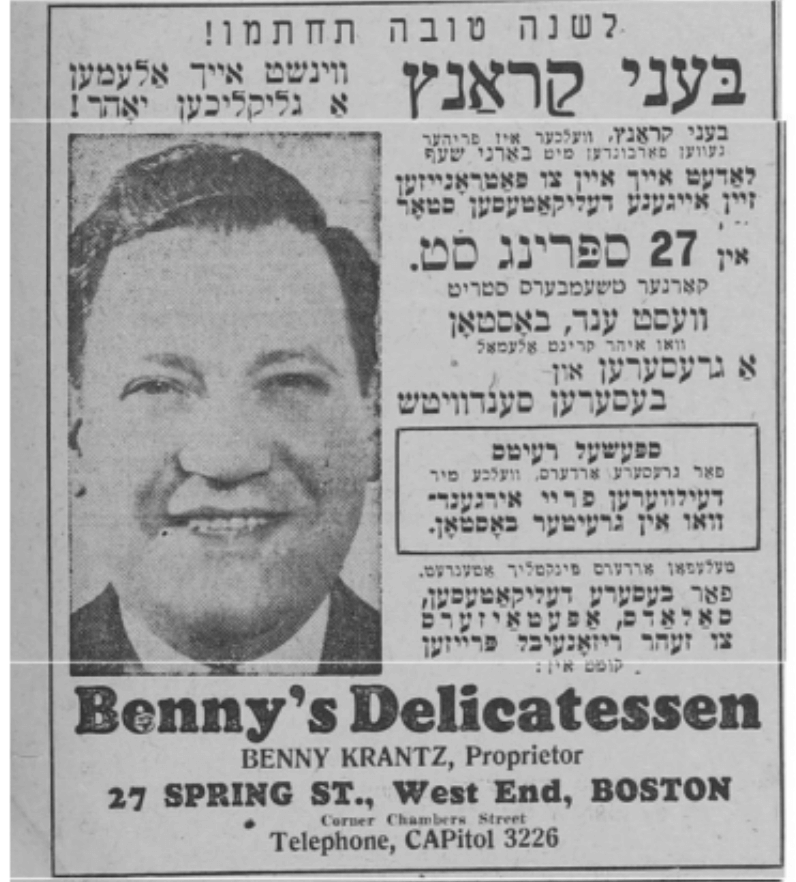

Benny’s Delicatessen opened in the early 1940s at 27 Spring Street. Benny Krantz, a former partner of Sheff, struck out on his own and founded his own place. Hymie Gordon’s Deli had locations on both Poplar Street and at the corner of Cotting Street and Wall Street. They served excellent sandwiches until the 1950s. Ganek’s Delicatessen stood at 57 Phillips Street. Louis and Fannie Ganek operated seven days a week, their door always open to neighbors.

The Bakeries: Filling the Streets with Aromas

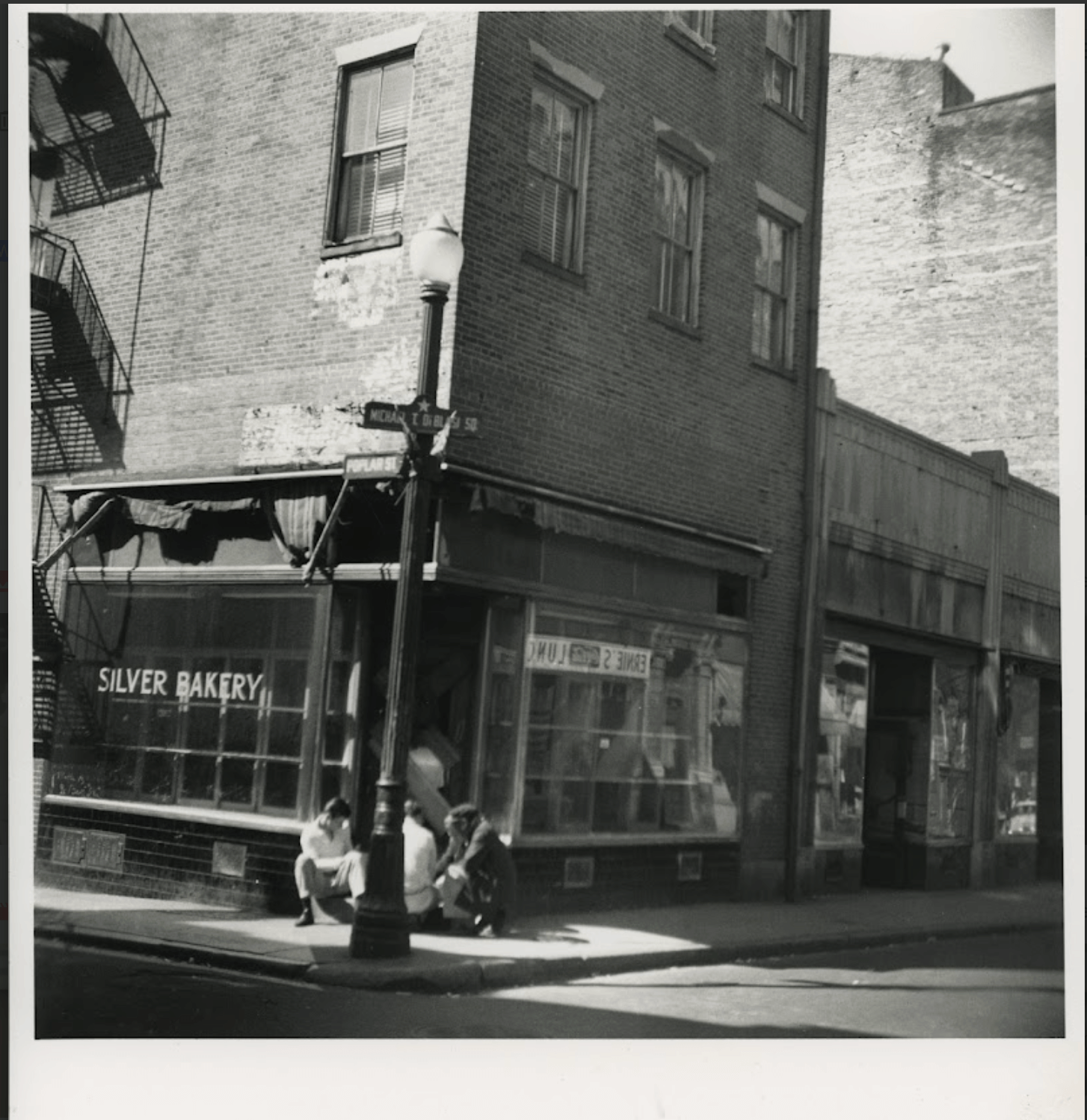

The Silver family operated Silver Bakery at the corner of Poplar and Spring streets (and later at 194 Chambers Street). It became legendary for its honey cake and “cat pies”—day-old pastry spread with sugar and spices, cut into squares and sold for one penny. Residents recalled the “fresh pastry” smells that wafted down the block. Rolls cost 2¢ each, bread 10¢, and honey cake 15¢ a pound.

Tillie Silver was the matriarch who owned and operated Silver’s Bakery. After her husband Max passed away in 1925, Tillie continued to run the bakery as a widow while raising their six children. The Silver family stewarded the bakery from roughly 1906 until Tillie sold the business in 1949. This dedication made them a pillar of the neighborhood’s Jewish life.

Barnard’s Bakery on Cambridge Street held special significance for West Enders. Mary Jackman recalled that it had been there “for over a century.” She said “I’ve never tasted doughnuts like them. And frulekach that I’ve never been able to find since.”

Hurwitz Bakery on Parkman Street near North Russell Street gained renown for its hot bagels and fresh bread. They delivered “hot” loaves across the street to local delis. Kravitz Bakery, also on Parkman Street, supplied the warm rye bread that made Klayman’s corned beef sandwiches so memorable.

Godfried’s Home Bakeries on 29 Causeway Street was remembered for its unique “icicles” confections and jelly-filled “Bismarks” donuts. Edith and Morris Godfried operated the bakery from 1933 until the demolition of the Old West End in 1958-59. After closing, their son opened a new Godfried’s Bakery on Route 1 toward Saugus. In a letter to The West Ender in March 1988, the Godfrieds noted that they never lived in the West End, but “enjoyed many years of business there.”

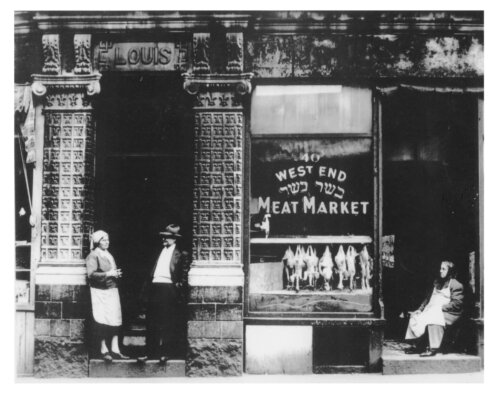

Kosher Butchers: Maintaining Dietary Tradition

The formation of the Butcher Trust in 1892 set fixed prices for kosher beef. As a result, two kosher meat cooperatives in the West End came together. Their price fixing continued with the backing of the Jewish Advocate newspaper.

Mezikofsky & Sons, a kosher meat market located at 28 Poplar Street, proudly advertised “The best kosher meats at the best prices” with “guaranteed kosher meat.” The shop not only sold kosher meats but also manufactured kosher salami, bologna, and hot dogs. Mezikofsky became a chain in the early 1930s with shops opening in Chelsea and Lynn.

The butcher shop’s pricing demonstrates how families observing kosher dietary laws could afford to eat meat. In May of 1930, for example, veal breast was 18¢ a pound, chuck steak was 25¢ a pound, brisket was 25¢ a pound, fresh soup bones were 10¢ a pound, and the “best pickled tongue” was only 25¢ a pound. At this time, the average wage was around 43¢ an hour. A family could thus afford almost two pounds of meat for one hour of work.

Other kosher butchers included Maxie’s Meat Market on 3 Leverett Street. The owner, Maxie Horn, served customers in Polish, Russian, and Yiddish. West End Meat Market was on Spring Street and Izzie the Butcher on Chambers Street was a strictly kosher operation.

Grocery Stores and Markets

Most grocery stores in the West End operated on an informal credit system. People would charge groceries all week and pay when they could. This was a crucial accommodation for families living paycheck to paycheck.

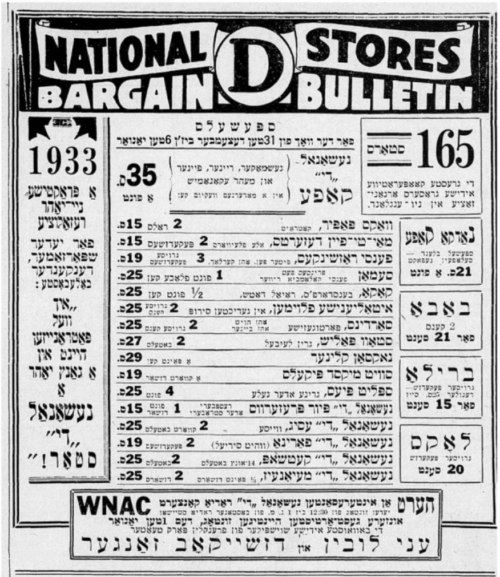

Located at Spring and Poplar Streets, The National D Store (also known as National Supermarket) was owned by the Erpet family. This business transitioned from small family grocers to early chain store operations while maintaining family ownership. The store advertised itself as “Individually Owned—Co-operatively Operated.”

The National D Store had affordable pricing even in May 1930 during the Great Depression. Fresh eggs cost 10¢ a dozen, fresh butter was 21¢ per pound, coffee was 15¢ per pound, and 5 pounds of sugar was 19¢. The store proudly advertised “The best ice cream in the neighborhood—for your Sabbath pleasure—29¢ a quart” and rolls “baked fresh daily in our own bakery.” Cake ingredients and ice cream at these prices would have cost around an average hour of labor meaning that many could access it.

Schnipper’s Fruit Store was a classic “Ma and Pa” shop on Spring Street. Norman “Fat” Schnipper was well-known for his lively, talkative manner that made shopping a social experience. Jim Campano wrote of Schnipper as a neighborhood legend. He supposedly weighed between 450 and 500 pounds. Rumors of his exploits included eating a small Table Talk pie in one gulp and needing a custom-sized casket when he died.

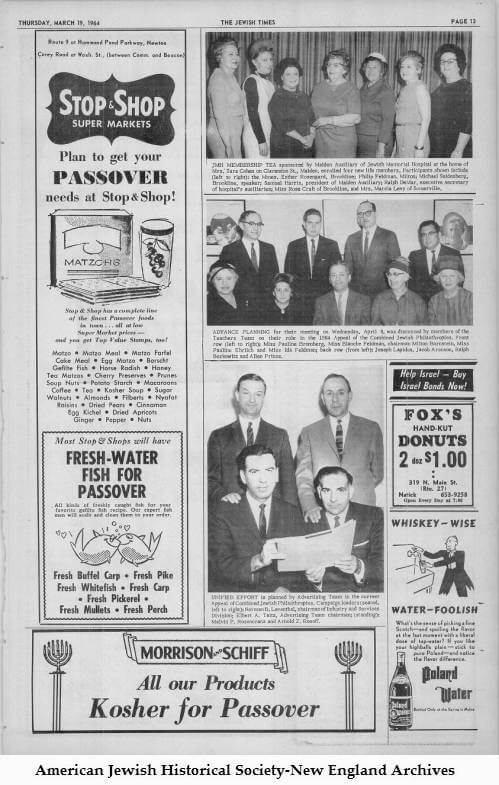

Another instance of family grocers expanding into chains was Rabinovitz Brothers’ Chain Store Creameries. A Jewish-operated grocery store in the Old West End, it later became part of the Economy Grocery chain. Eventually this business became the Stop & Shop supermarket chain. Jackman witnessed this transformation firsthand: “Stop & Shop started in the West End on Spring Street. Rabinovitz himself was there.”

Minnie White’s store on Green Street between Leverett and Chambers was a neighborhood institution that had “everything under the sun.” For a penny, children could buy wrapped candy, and if the candy had a white dot, they’d win a candy bar. Grossman’s Market on Myrtle Street sold meat, fish, and groceries. Mrs. Miller’s Variety Store at South Margin and Norman Streets was famous for its big jars of pickles on the counter.

Food Specialty Shops & Restaurants

The Causeway Cafeteria served “Jewish food” at the junction of Causeway and Leverett Streets. They were located in the heart of the business strip by the Boston Garden and North Station. Maish Sherman remembers that matzo ball soup or “two frankforts, beans and a half loaf of rye bread” was 25¢.

In a 1981 interview, Marie & Lucy Gigante and Josie Savage reminisced about the Causeway Cafeteria

Lucy: “I used to love that cafeteria.”

Josie: “I used to live there.”

Marie: “That was our favorite place. Nice soups, hot soups for a quarter – they had a bowl of soup that would knock your head off.”

Lucy: “They’d have a pea soup—oh, it was delicious. With the Jewish bread with the cream cheese… Not being Jewish myself, it was very reasonable.”

The editor of the Westy News for the West End House, Hy Rosenberg of 33 Blossom Street, described painting the Cafeteria three times in an oral history interview. He remembered it as a “big hangout” for bookies. Al Tabachnik had a weekly tab there. Eileen Marotta (Hartnett) said one could often “find him sitting alone, very content, eating a chicken with his bare hands.”

New England Kosher Restaurant, which opened in 1925 at 76A Green Street, was run by C. Lampert and E. Schwalbe. Ahead of their “Grand Opening”, they advertised the restaurant as a place “Where you will receive at every time fresh, clean, tasty foods at moderate prices.” Mr. Warshefsky’s Dairy Store on Chambers Street sold fresh butter and buttermilk.

Shapiro’s Liquor Store, also known as Causeway Liquors, opened in 1886. Charles Shapiro ran the store alongside his Tonic Plant on Causeway Street, next to Godfried’s Bakery. This family liquor store was the first to get a license after Prohibition. Charles Shapiro was known as “the Mayor of the West End.” His daughter, Gladys Shapiro, remembered that he gave jobs to neighborhood kids on his delivery truck. Charles and Gladys Shapiro would go on to lead the fight against evictions from the West End during urban renewal.

Street vendors added to the commercial vibrancy. On hot nights, vendors would sell “ice cold slush” at various locations. The “crab man” sold crabs from a pushcart, wheeling it through the West End’s many streets. Patty Lombardi-Sacco remembered the daily rhythms of street commerce: “Iceman, oilman & crabman shouting ‘gouda gouda’ (hot hot). We would buy the crabs off the push cart, hot & then sit on the stoop & enjoy.”

Solomon Padulsky, known as “Shlemky,” was a person with dwarfism who ran a newspaper stand at the corner of Causeway and Canal Streets for thirty years. He sold newspapers to commuters. Beyond his legitimate business, Shlemky also booked numbers and had a significant bookmaking operation. Every night he would return home with his apron bulging with coins. His whole family would sit around the kitchen table helping him count the money.

Thanks in part to the local Jewish-run businesses in the West End, residents could find all they needed within a short walking distance. These grocery stores, restaurants, specialty shops, and the people who ran them helped build the foundation of a tight knit community.

Article by Amir Tadmor, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Santo J. Aurelio “Jews and Italians in the West End of Boston, 1900-1920” May 7, 1984, The West End Museum Archives; Meaghan Dwyer-Ryan “Ethnic Patriotism: Boston’s Irish and Jewish Communities, 1880-1929,” dissertation, (Boston College, August 2010); Isaac M. Fein, Boston: Where It All Began – An Historical Perspective of the Boston Jewish Community (Boston Jewish Bicentennial Committee, 1976); Forṿerṭs (Forward) newspapers, 1900-1958, from Historical Jewish Press, The National Library of Israel and Tel Aviv University; Mary Jackman, “Bruno Interview 0018,” October 8, 1980, The West End Museum Archive; Eric Moskowitz, “Boston’s Last Tenement – an Island Awash in Modernity,” Boston Globe, August 15, 2015; Leonard Nimoy and Christa Whitney, “Leonard Nimoy Remembers Boston’s West End Neighborhood” (Yiddish Book Center, February 6, 2014); Josie Savage, “Bruno Interview 0029”, October 24, 1978, The West End Museum Archive; Jeanne Schinto, “Israel Sack and the Lost Traders of Lowell Street” Maine Antique Digest, April 2007, accessed from the West End Museum Archive; United States Department of Labor Handbook of Labor Statistics – 1936 Edition (Washington, D.C. United States Printing Office, 1936), 916; The West Ender Newsletter, 1985-2022.