Kane Simonian

The distinct name of Kane Simonian belonged to the man who either controlled or influenced Boston’s urban development for over 40 years. He managed the city’s first federally funded urban renewal projects under the Boston Housing Authority. In 1957, he became the first director of the Boston Redevelopment Authority. Simonian’s long, tumultuous, and sometimes controversial career left an indelible mark on many of Boston’s citizens and its landscape.

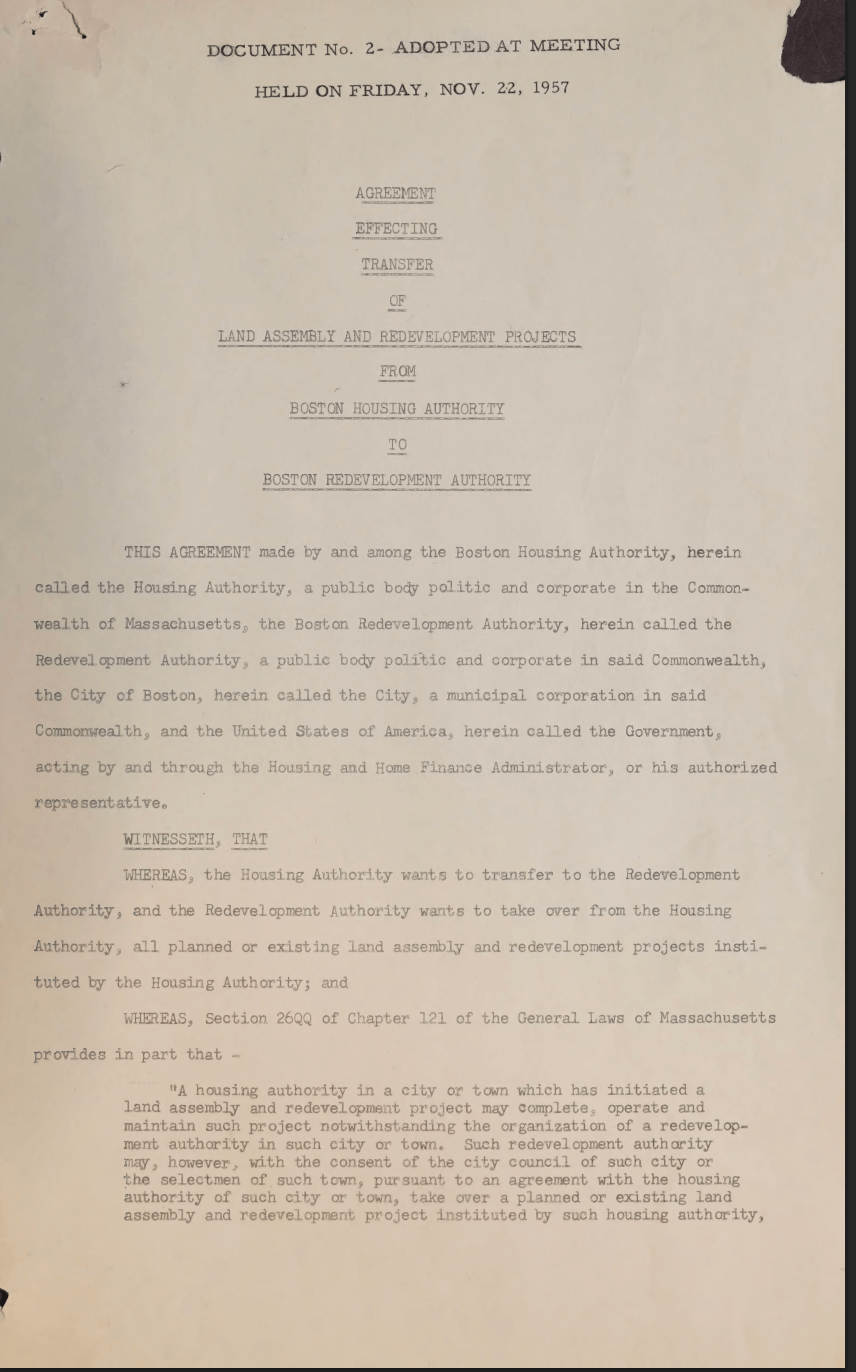

In 1957, under pressure from business leaders dissatisfied with the pace of Boston’s urban renewal program run by the Boston Housing Authority (BHA), Massachusetts lawmakers created a new agency named the Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA). The BRA would oversee all current and future urban renewal projects and essentially all major land development in Boston. It would be a semi-autonomous agency with board oversight and stronger executive leadership. Kane Simonian, who had led the BHA’s urban renewal department, was named the BRA’s first director.

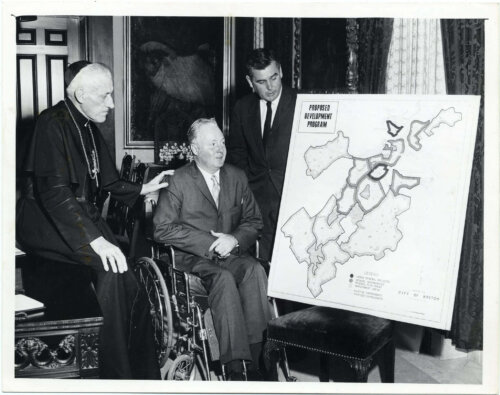

Simonian was born into an ethnic Armenian family in 1912 “by Caesarean section on the kitchen table of his parent’s East Boston apartment.” He earned an undergraduate degree from Harvard University in 1933 and attended Boston College Law School. Simonian served in the U.S. Army during WWII, and worked at the Veterans Administration after the war. In 1946, he joined the BHA as an administrator. Simonian was active in politics. He worked for John F. Kennedy’s congressional campaign in 1947 and John Hynes mayoral campaign of 1949. He was also a close friend of the future U.S. Speaker of the House, Thomas “Tip” O’Neill. Possibly in return for Simonian’s past support, Mayor Hynes appointed him chief of the BHA’s urban renewal and slum clearance operation in 1951. The position paid $7,000 a year, the equivalent of $90,000 in today’s money. In his new position, Simonian had to hit the ground running.

In quick succession, Simonian had to fund and execute projects in Mattapan, the South End, and the West End. He found himself in the spotlight as the builder of Hynes’s New Boston. Yet, the projects he led also attracted scrutiny from citizens, the press, politicians, and the business community. The New York Streets clearance in the South End began in 1955, but by 1961 only two of 16 parcels were available to business tenants. The West End Project, announced in 1953 and planned to commence in 1954, had yet to begin by 1957. Despite this lack of momentum, officials still maintained faith in the skills and experience of Simonian who was allowed to continue the mission as BRA’s director.

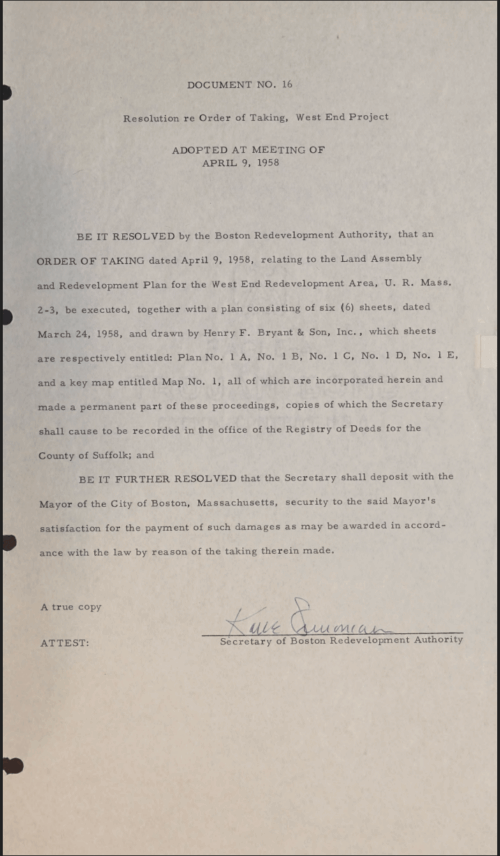

From 1957 until the inauguration of Mayor John Collins in 1960, the West End Project took up most of the BRA’s focus. The $200 million slum clearance plan was designed to replace over 600 hundred tenement buildings with luxury high-rise apartments and displace 12,000 residents. Simonian faced strong criticism from the Boston City Council for an inadequate bidding process for a West End developer. He also had to endure protests by West End residents and their political supporters. Despite the delays and hurdles, Simonian was finally able to begin demolition of the West End in the early summer of 1958.

While Simonian tackled the West End, Collins began secretly courting a new leader for the BRA, namely Edward Logue, the rising star of urban renewal, currently reshaping nearby New Haven, CT. When Collins announced the hiring of Logue in 1961, at a higher salary ($30,000) than his own, Simonian viewed it as a demotion. Quickly, he took legal action against the BRA and Logue to “cease and desist from including himself [Logue] into that office.” Simonian lost the case and Logue assumed power as BRA director. As compensation, the Massachusetts legislature granted Simonian lifetime tenure as the BRA’s Executive Secretary. This put him in charge of the BRA’s real estate management, engineering, and record keeping. In addition, perhaps as punishment, Logue left Simonian in charge of the increasingly unpopular West End Project. The two stayed as far away from each other as possible until Logue’s departure in 1967.

For the next 30 years, Simonian outlasted Logue and a string of eight future directors. His role as Executive Secretary made him a proverbial “spider in the web”. He had enough power to become both a “nay sayer” when desirable (as suggested by Boston journalist Tom Hynes), or an agent of positive action for the BRA. At times throughout his career, Simonian faced criticism, especially over his involvement in dispensing West End parking lot concessions. Others saw the lucrative consulting contract he gained immediately after retiring with a healthy pension as political favoritism.

Simonian died in 1996 leaving behind a complicated legacy. He was a champion for those in favor of creating a New Boston. He was a firm believer in urban renewal, with the brains and toughness to successfully navigate the federal financing bureaucracy and Boston politics. Some saw him as an imposing figure, often gruff and sometimes explosive. One BRA director called him “ferocious” after trying to force his resignation. Others saw him as a “wise counsel”, possessing a “first-rate sense of humor.” Former West End activist Jim Campano accused Simonian and others of “wholesale heartlessness” for the false promises made to West End residents in the original renewal plan and the poor treatment of the displaced.

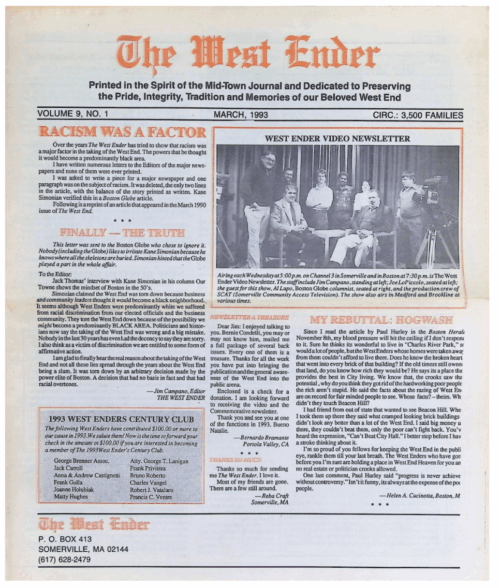

Simonian fought the tarnish on his career left by the demise of the West End right up to his death. For his part, he claimed he was simply following orders, forced to work with the limitations of the programs, federal and otherwise, available to him at the time. In a January 4, 1990 interview with Boston Globe reporter Jack Thomas, Simonian’s frustration over this criticism rose to the surface. He listed all the organizations that were in favor of the West End Project at the time, and said, on imaging a West End without renewal:

“And do you know what probably would have happened to the West End? It would have become a black neighborhood, like the South End, which is no howling success.”

This statement opened up old wounds of former West Enders and made the front page of Campano’s, The West Ender newspaper.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: The Boston Globe, Feb 15, 1951| Feb 16, 1951 | Jan 9, 1952 | May 14, 1953 | Jun 22, 1956 |Jul 20, 1956 | Feb 11, 1961 | Aug 18, 1963 |“Interview with Jack Thomas” Jan 4, 1990 | Feb 28, 1994 | Jun 2, 1996 | Kane Simonian, Obituary, Jul 27, 1999 | 29 July 1999 | Aug 1, 1999 | Apr 28, 2009; Lizabeth Cohen, Saving America’s Cities : Ed Logue and the Struggle to Renew Urban America in the Suburban Age, (New York: Picador, 2019); Thomas H. O’Connor, Building a New Boston: Politics and Urban Renewal, 1950-1970, (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1995); The West Ender Newsletter, March 1990.