When Barry's Corner Said, 'To Hell With Urban Renewal!'

After learning from the example of the West End, one of the neighborhoods who fought back against urban renewal was the tiny area of Lower Allston called Barry’s Corner. A beloved working class area, Barry’s Corner residents did their best to push back against the specter of urban renewal through protest and public pressure. Ultimately, they were only able to prevent luxury apartments from replacing their community.

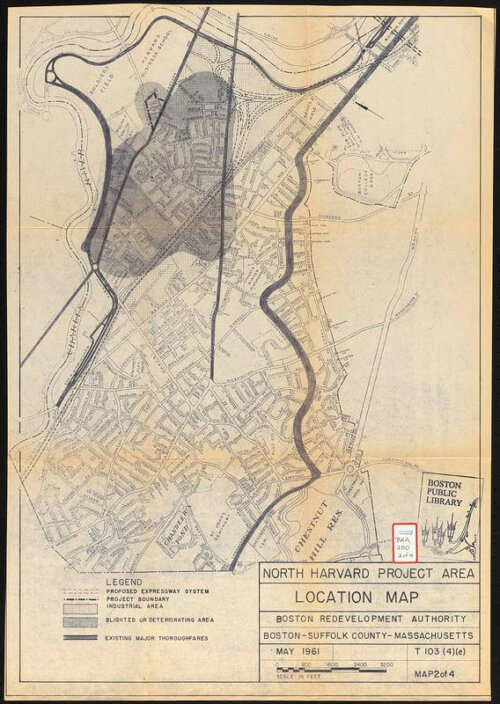

In the aftermath of urban renewal projects in Boston’s West End and in the New York Streets of the South End in the 1950s, the city turned its attention to its outlying neighborhoods. The tiny Barry’s Corner neighborhood, full of working class families, became a target. The destruction of this section of Lower Allston in 1965 by the Boston Redevelopment Authority was a less urban example of urban renewal as the neighborhood was much less dense than previous targets. But the little neighborhood with only 71 families wouldn’t go down without a fight.

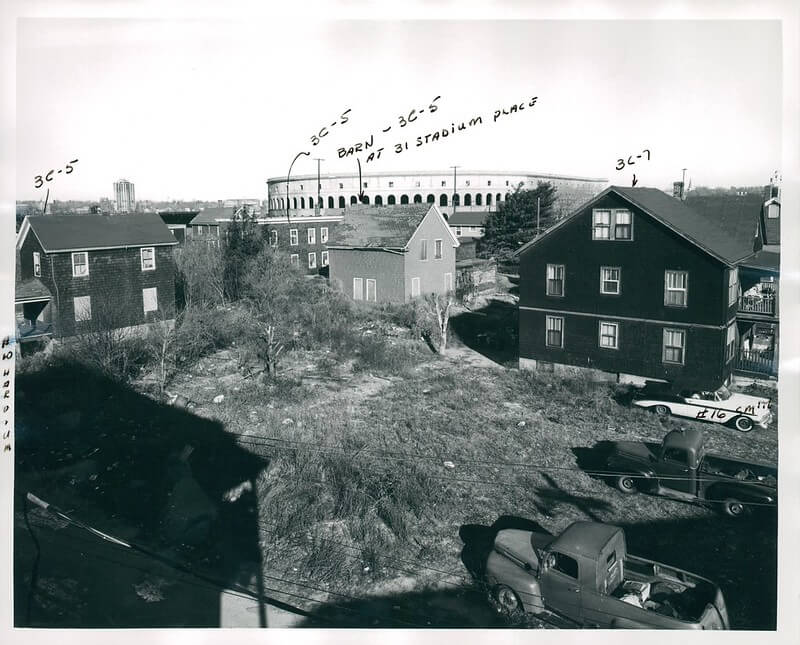

North or Lower Allston is defined as the area north of Interstate 90 and south of the Charles River. It is located across the river from Harvard Square and is the location of the Harvard Business School. Lower Allston lacks access to rapid transit, but is well served by buses. In the mid-twentieth century, residents could live there without a car. The area of Lower Allston known as Barry’s Corner was centered at North Harvard Street and Western Avenue. Before urban renewal, Barry’s corner was mostly home to working class Allstonians living in two and three family homes. Comprising a tight 9.3 acres, Barry’s Corner contained only 52 structures.

The squat footprint allowed for a more suburban feeling with a caveat. Former resident Bernard Redgate described life in Barry’s Corner as having “a connection with people that you don’t have in the suburbs.” Barry’s Corner was a tightly knit community, mostly Irish and Italian, with some families of Polish and French descent. Francis Bakke, recalled Barry’s Corner fondly, saying it was “a good place to live. There was a lot of pride in our neighborhood. Children who grew up there often stayed on as adults. It was common to find three generations of a family living there.”

However, a development team saw an opportunity to build a 10 story luxury apartment building in the place of the working class neighborhood. Residents noticed unknown people in the area in the summer of 1961, but didn’t realize why. It was not until that October that residents realized that officials had been scoping out of the area. Knowledge of the project arrived when residents turned on the news one evening. The announcement “came like a bolt”, Bakke remembered, when the story ran on Channel 4 news. Barry’s Corner residents were blindsided.

The BRA’s plan felt especially brazen to the residents. Their homes, described as blighted, were going to be destroyed and replaced by luxury buildings, paid for with federal money. The projected yearly tax revenue was $150,000, ten times the $15,000 of the 52 homes. The city and developers would win, but the residents would lose. Despite a similar promise to West Enders to make “every effort” to find “suitable new homes” for residents, Barry’s Corner residents were skeptical. They organized quickly. Marjorie Redgate, owner of the neighborhood’s Ready Luncheonette, was a leader in the fight. They invited evicted residents from earlier urban renewal projects to speak, including Wanda Zachewicz, a member of the Committee to Save the West End. Residents formed a group called Citizens for Private Property and picketed near the State House and Mayor John Collins’ home in Jamaica Plain.

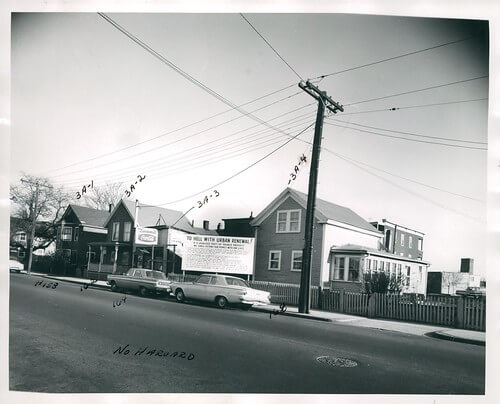

At a public hearing for the project, residents interrupted proceedings by chanting “Get out!” to developers. A local priest, Timothy Gleason of St. Anthony’s Church exclaimed “Barry’s Corner is not a slum area. These people are good, God-loving people. The word blighted means rot and decay. There is nothing rotten, nothing decayed in Barry’s Corner.” Locals left Ed Logue, the BRA Administrator, “visibly shaken” after hearing the boos and jeers during a public hearing. The neighbors installed a billboard in Annie Soricelli’s front yard that read “To Hell with Urban Renewal.” Homemade banners with similar sentiments hung from several houses. One banner proclaimed, “The Rich get Richer and The Poor get Homeless.” The Barry’s Corner residents even rented Faneuil Hall in June 1963 for a city-wide rally against urban renewal.

But it was all for naught. A five to four vote by the Boston City Council ruled in favor of the BRA’s plan. In late 1964, Barry’s Corner residents received letters informing them their homes were being seized by eminent domain. They were even required to pay the BRA rent while remaining. By mid-1965, more than half the families left. Those who remained weren’t leaving quietly. The situation became tense when the city sent moving vans to evict the holdouts. Residents protested in the streets, joined by activist student groups from Harvard and residents displaced from other city neighborhoods. Several people were arrested over multiple days of protests. All the while, bulldozers began taking down empty buildings. Only the Redgates and a few others were still in their homes.

Mayor Collins, under significant political pressure, was said to cave in to all the negative publicity. But did he? The Mayor did appoint a blue-ribbon commission to make an assessment. But the BRA ignored the panel’s recommendation to allow the residents to buy back their homes. The BRA replaced the plan for luxury apartments with one for low- and middle-income housing through a non-profit inter-faith group, the Committee for North Harvard (CNH). Marjorie Redgate and her family still held out, but the lack of any real support from the Greater Allston/Brighton community was particularly glaring. Redgate pointed out the failure of the Allston Civic Association and its president, Joseph M. Smith, about Barry’s Corner, saying:

“Why didn’t he appear at even one of the many public hearings that were held and let his views be known. Joe was never a supporter of the residents of North Harvard Street. As the residents were fighting against the luxury apartments, the best Joe could do was to remain silent, and while we fought to keep our homes in the final hours, Joe was fighting against us, serving in the ranks of the CNH”.

The last few homes in Barry’s Corner, including Marjorie Redgate’s, were leveled and removed in 1969 after another large protest that saw 14 people arrested. The Redgates, surrounded and out of options, finally allowed movers into their house, if only to protect their supporters and police from a violent clash. By 1971, the Charlesview Apartments opened. The lowrise apartments stood on the site of Barry’s Corner until 2015 when they were demolished. Developers constructed a new low and middle income complex at the nearby Brighton Mills Parcel. Today, Harvard University owns much of Barry’s Corner as part of its expansion into Allston. As of 2026, much of the footprint of the once loved neighborhood of Barry’s Corner is once again a vacant, undeveloped lot.

Article by Irwin Levy, edited by Jaydie Halperin

Sources: Danish Bajwa, Michal Goldstein, and Brandon L. Kingdollar, “How Harvard Moved Into Allston,” (The Harvard Crimson, September 16, 2022); Charlesview, Inc. “History,”; City of Boston Planning Department, “Draft Project Impact Report: Charlesview Redevelopment,” (July 24, 2009) | “Project Notification Form,” (February 11, 2008); Sarah Conlan, “After the West End: The Fight for Barry’s Corner”, (City of Boston: Archives and Records Management, April 17, 2020); Sabrina Doshi, “Get to Know Allston: A History,” (Harvard School of Engineering: News, December 3, 2020); Rachel Hook, “The Land Boston Forgot: The (r)evolution of Barry’s Corner and the search for Annie Soricelli,” (Binj Boston, October 14 2015); Bill Marchione, “Remembering Old Allston-Brighton: Battle to save Barry’s Corner” for the Brighton-Allston Historical Society (The Allston-Brighton, March 28, 2008); Bill Marchione, “Barry’s Corner: The Life and Death of a Neighborhood”, The Brighton-Allston Historical Society, (1988); Amelia Mason with Megan McGinnes and Hanna Ali, “Allston: A Boston neighborhood guide,” (WBUR, September 1, 2023, updated July 22, 2024); Amelia P.S. Springer, “Allston Is Gentrifying and Harvard Is To Blame,” (The Harvard Crimson, February 11, 2025); Jim Vrabel, “A People’s History of New Boston,” (Boston: University of Massachusetts Press, 2014); Sarah Wu, “Lessons from Barry’s Corner,” (The Harvard Crimson, May 10, 2017); Mark Zurlo, “The Development Of Barry’s Corner And What It Means For Allston” (Allston Pudding, December 16, 2013).