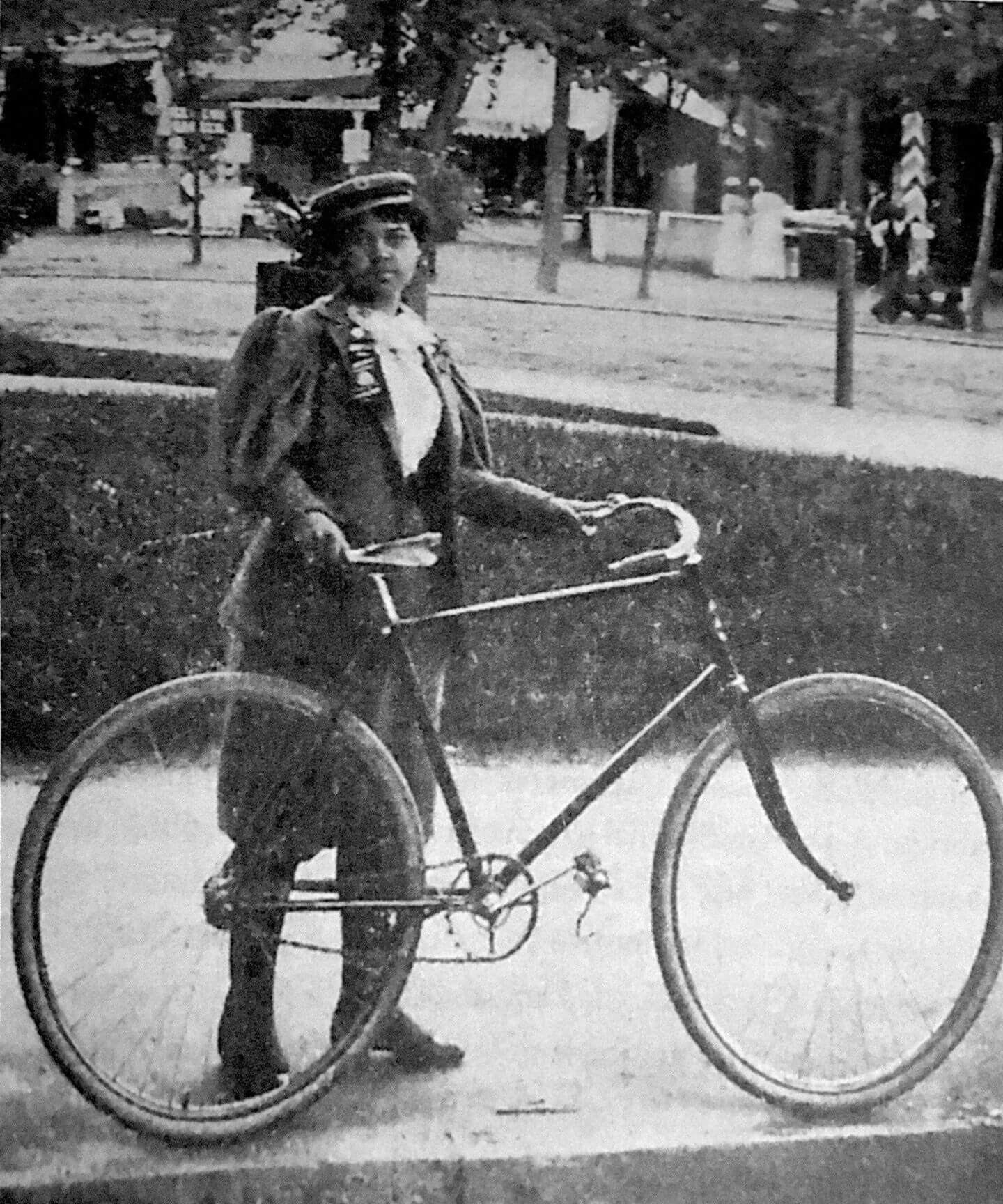

Kittie Knox

Kittie Knox was a mixed-race cyclist who used her skills as a seamstress and cyclist to challenge gender and racial perceptions taking over the League of American Wheelman in the 1890’s.

Katie “Kittie” Knox was born to a white mother and black father in Cambridge in 1874; when her parents separated in the early 1880s, Kittie moved with her mother and brother to the corner of Irving and Cambridge Street in the West End. Knox worked as a dressmaker and seamstress, but her passion was in bicycling. In 1893, Knox was a founding member of the Riverside Cycling Club in Cambridge, the first black cycling group in the United States, and joined the League of American Wheelmen (LAW) that same year — although many of the League’s chapters barred black participation. By 1895, at the age of twenty-one, Knox broke the color barrier at LAW’s national competition, or meet, in Asbury Park, New Jersey. She had also lived a few blocks from Annie Londonderry, the West End resident who became the first woman to ride a bicycle around the world.

At the national meet, Knox was sent away from hotels because of her race, and LAW officials refused to give her a credential badge, but she persisted for inclusion. The New York Times reported that Knox rode to the meet in knickerbockers, considered men’s clothing, on a men’s bike doing “a few fancy cuts in front of the clubhouse.” The LAW Bulletin in 1895 responded to a letter asking how Knox, a black woman, could be a member, and League officials replied that Knox could stay because the whites-only membership clause was not written until 1894, the year after Knox joined. Knox was more skilled, and faster, than most men riding at the time, and was the LAW’s ride leader at its Massachusetts summer meet. In the Partridge White Ribbon Open ride, during a thunderstorm, Knox was the only woman to cross the finish line. Despite these accomplishments, the League pushed her out some members threatened to quit if she stayed on, and the organization did not repudiate its original whites-only policy until 1999.

Knox died of kidney disease in 1900 at Mass General Hospital, at the age of twenty-six. The Smithsonian Libraries recently spotlighted Knox on Twitter in January 2020, and concluded that this West Ender “helped democratize cycling – for both women and cyclists of all races.”

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti