David Walker

David Walker, an African-American abolitionist who lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill, published a prominent book of the anti-slavery movement after traveling to many parts of the United States.

David Walker was born in Wilmington, North Carolina in 1796 to an enslaved Black man and a free Black mother. Walker was subsequently born free because slave codes in the American South established that African-American children inherited the legal status of their mothers. As a young adult, Walker moved to Charleston, South Carolina and joined the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church there. The AME Church had a strong activist tradition that likely shaped Walker’s strong commitment to abolitionist advocacy. Walker traveled widely across the South and West of the country, and by the 1820s returned east to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. He eventually settled in Boston in 1825, owning and operating a used clothing store at City Market. Walker and his wife Eliza Butler, whom he married in 1826, moved to the north slope of Beacon Hill in 1827 – where the free Black community of the old West End resided. The Walkers had two children, Lydia Ann Walker (who died of tuberculosis before the age of two, in 1830) and Edwin Garrison Walker (1830-1901).

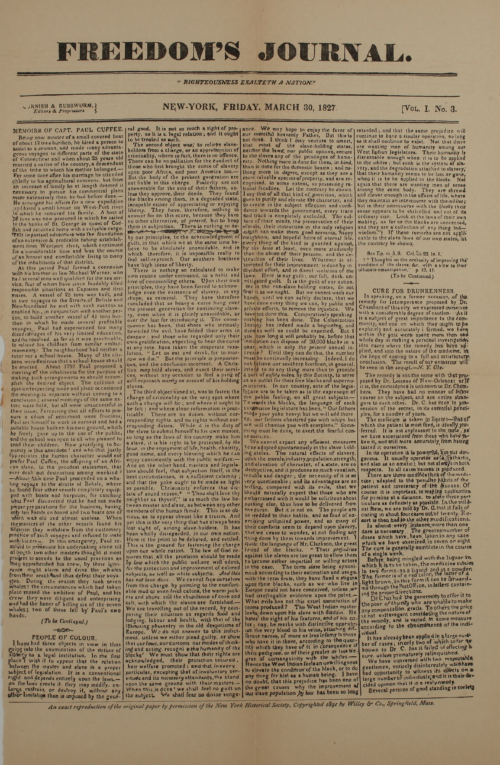

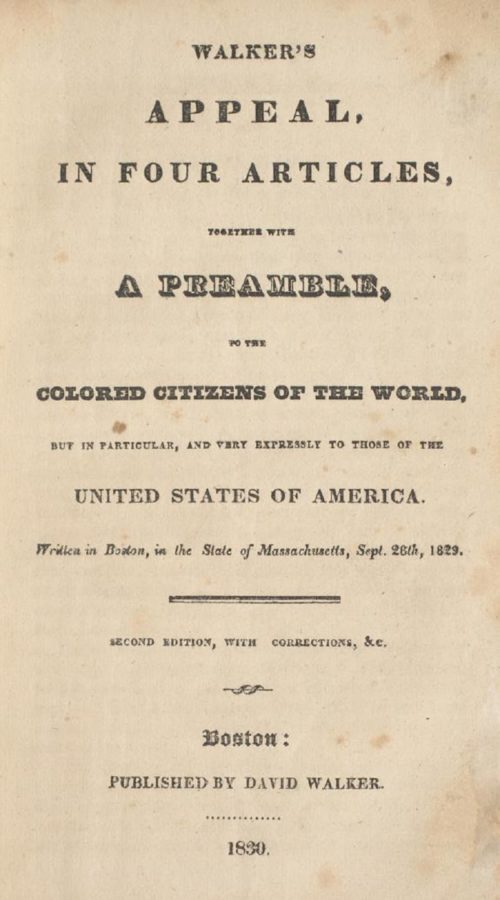

While in Boston, Walker devoted himself to activism against the oppressive institution of slavery. He was the city’s “subscription agent” for Freedom’s Journal; based out of New York, it was the first African-American owned newspaper. Walker also belonged to the Prince Hall Freemasonry and the Revere Street Methodist Episcopal Church, the latter founded in 1818 and led by abolitionist minister Rev. Samuel Snowden. The Walkers lived at 8 Belknap St. (presently 81 Joy Street) until 1829, when they moved to Bridge Street in the West End. Historian Donald Jacobs recorded that David Walker lived on Bridge Street in his list of 80 “Black Persons of Prominence Who Resided in Boston’s West End Section Prior to the Civil War.” In September of 1829, Walker published his influential book, Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World. The longer title emphasized that his primary audience was Black citizens of the United States.

Walker’s Appeal argued against the sheer hypocrisy of Southern slave owners who called themselves Christians, and implored free Black people such as in Boston to speak out against slavery. He commented on his travels throughout the South and West and confirmed from first-hand observation that African-Americans throughout the United States faced deep levels of racism and segregation, including in Boston. Walker’s business connections were instrumental to the wide distribution of the Appeal, especially to its readership among enslaved people. He sold clothes to sailors who wanted to bring copies of the book on their trips down South. As the Appeal quickly became a popular, inspiring text for enslaved people, Southern states passed laws prohibiting enslaved people from reading, and others from distributing abolitionist literature. Slave owners had incoming ships searched for copies of the Appeal, but Walker often ingeniously sewed the book into the lining of supportive sailors’ clothes. The revised, third edition of the Appeal in June 1830 responded to Southern ports treating Walker’s book as dangerous contraband, and Walker passionately wrote against what this said about slave owners’ oppressive actions:

Why do the Slave-holders or Tyrants of America and their advocates fight so hard to keep my brethren from receiving and reading my Book of Appeal to them?–Is it because they treat us so well?–Is it because we are satisfied to rest in Slavery to them and their children? […] Why do they search vessels, &c. when entering the harbours of tyrannical States, to see if any of my Books can be found, for fear that my brethren will get them to read. Why, I thought the Americans proclaimed to the world that they are a happy, enlightened, humane and Christian people, all the inhabitants of the country enjoy equal Rights!!

David Walker died in August 1830, two months after the Appeal’s third edition. Contemporaries believed that Walker was poisoned, but historians later inferred that he died of tuberculosis. Although Walker wrote that he did not intend to publish any further editions of the Appeal, he would certainly have remained active in the abolitionist community of Beacon Hill had he not died so soon.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Walker’s Appeal, in Four Articles; PBS; National Park Service; The David Walker Memorial Project; Cape Fear Historical Institute; “Partus sequitur ventrem: Law, Race, and Reproduction in Colonial Slavery” by Jennifer Morgan; Courage and Conscience: Black & White Abolitionists in Boston by Donald Jacobs; What Hath God Wrought by Howe; BlackPast