Leon W. Bishop

Leon Bishop lived in the West End in 1902 when he became one of the first amateur radio pioneers in Boston and the United States, broadcasting wireless radio concerts to listeners throughout the city.

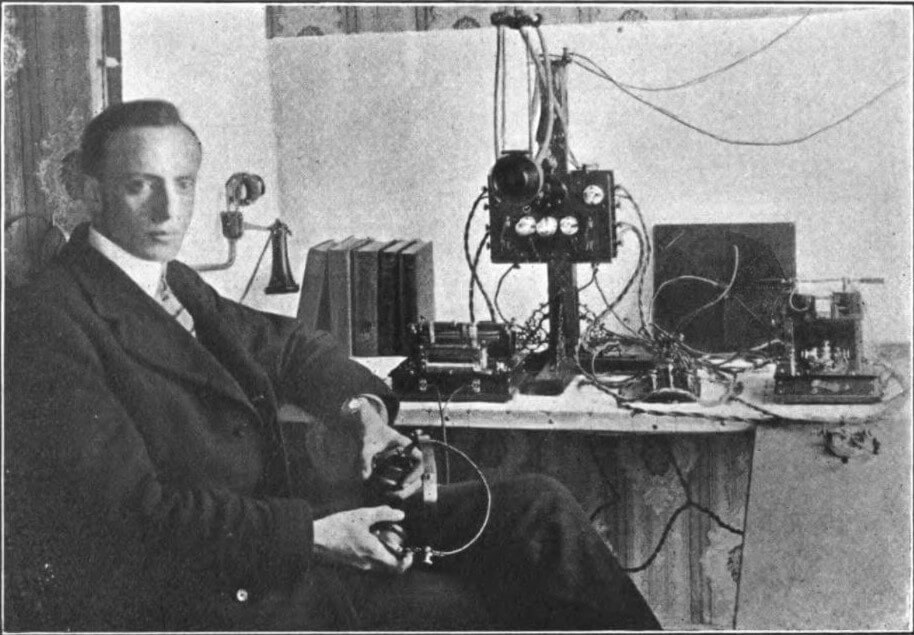

Leon Wilbur Bishop moved from New Jersey to the West End in 1902, the year he first resided at 18 Irving Street. That year, Bishop set up a radio station and laboratory in his home where he conducted pioneering amateur radio experiments, shortly after Guglielmo Marconi and George Kemp, in 1901, achieved the first transatlantic radio signal of Morse code. Living on Irving Street, Bishop made a radio transmitter that included headphones and a telephone receiver, with an initial range of two miles. He had to test his signal with ships docked nearby, or with the Charlestown Navy Yard, because there were not yet other local amateur radio stations he could communicate with. This quickly changed by 1905, when Bishop started working with Herbert Hammett, who had his own station on 4 Blue Hill Avenue in Roxbury. Bishop and Hammett were testing telegraphy with similar methods as Marconi, but the two soon began working on a wireless telephone, or “radiophone.” In 1908, Hammett confirmed that he could hear Leon Bishop’s voice through the receiver from two miles away. The following year, their radiophone could be heard at stations 15 to 20 miles away. Bishop was then inspired to host “radiophone concerts” from his station, where he could play music through his new wireless telephone for listeners far and wide. In 1909, Bishop advertised in a Lynn newspaper: “Wireless Operators, Attention – Get your receiver ready to hear the wireless telephone – Leon W. Bishop – Exhibition afternoon and evening concert at 5 and 7 Saturday.” The Boston Globe reported in 1934 that this announcement was likely the first public announcement of a concert by radiophone in the United States. Bishop reportedly lived in Lynn around the time he advertised his first radio concert, but he maintained a home radio station at his prior address on 18 Irving Street, according to a 1920 list of amateur stations by the United States Department of Commerce.

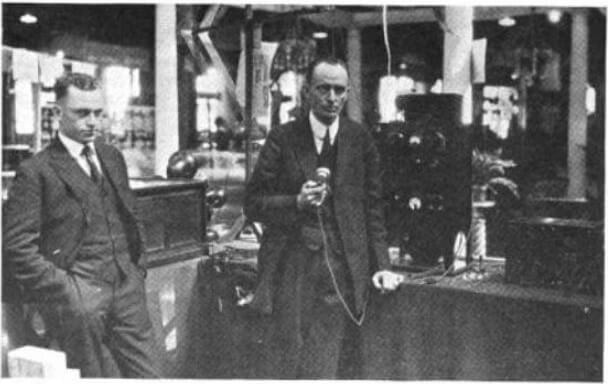

In his concerts, Bishop broadcast live performances from Hilda Kaplan, a soprano soloist from Boston, whose voice was heard by “wireless amateurs” across the city. The Globe declared in 1935 that “Boston may rightfully claim the distinction of giving to radio its first artist performer in the person of Miss Hilda Kaplan…” In 1910, Bishop displayed his wireless telephone to the public at the Boston Radio Exposition, held at the Mechanic’s Building on Huntington Avenue. In 1914, he continued his streak of successful experiments with a “magnetic and microphonic amplifier,” or a highly sensitive microphone for radio. During World War I, Bishop was recruited by Dr. Lee de Forest, who had experimented with radio telephony himself, to work for the Submarine Defense Association and the National Research Council. In this capacity, Bishop helped create a submarine detection system that the United States used to discover the location of German U-boats.

In 1920, large-scale radio broadcasts were first introduced to the United States when the public heard over the radio the results of the presidential election between Warren G. Harding and James Cox. But the work of amateurs like Bishop preceded this national breakthrough and continued through the decade. At the Boston Radio Exposition in 1921, also at the Mechanic’s Building, Bishop displayed a broadcasting station that transmitted speech and music heard 125 miles away, in Lebanon, New Hampshire. One periodical, The Wireless Age, reported that Bishop’s design was unique for using a loop as an antenna. Apart from his exhibits, Bishop wrote books and articles to educate amateur radio operators, such as The Wireless Operators’ Pocket Book of Information and Diagrams (1916). In 1922, Lloyd Greene credited Bishop with the emergence of “citizen radio broadcasts,” a phrase which suggests that early amateur radio experiments were instrumental to democratizing information and communication in the United States.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (“Divining Rod’s Secret Found,” October 23, 1921; Lloyd Greene, “Citizen Radio Broadcasts: How It All Started,” April 16, 1922; “Behind the Scenes in Radio,” April 24, 1935); The Wireless Age; Department of Commerce; Telegraph and Telephone Age