The Widening of Chardon Street

Before the City of Boston widened Chardon Street in the 1930s to develop the area around Haymarket Square, West Enders voiced their support for widening the street on a grassroots level.

On August 20, 1930, ordinary people in the West End collectively demanded an improved, widened Chardon Street by filling the office of Mayor James Michael Curley to express their needs. In the Mayor’s office, West Enders proposed widening Staniford Street as well as Chardon in order to address traffic congestion. Martin Lomasney, the former West End alderman and “political boss,” made an appearance and suggested that while Chardon St. should be widened, the widening of Leverett and Green Streets should take first priority. The City Planning Board took the opposite view, that Chardon Street should be prioritized because it would become an important approach to the East Boston tunnel. Lomasney had strong ties to the West Enders who amassed in Curley’s office, even when he no longer held office, and he was often a vocal critic of Curley’s proposals for developing Boston. When Curley proposed in 1931 that Boston build a central artery at a cost of $11,000,000, Lomasney objected to the cost and saw “several slick little jokers” in the bill, as well as an underlying motivation for some of the bill’s supporters to sell their land around Haymarket Square.

The West End Business Men’s Association played an influential role in increasing the legitimacy of the “Thoroughfare Plan of the City of Boston,” which included the widening of Chardon Street in order to facilitate traffic from Haymarket Square to the center of Boston. On January 8, 1931, Robert Whitten, the chief consultant of the City Planning Board, spoke to the Association during a dinner they held at the Bellevue Hotel, then on Beacon Hill. The West End’s business owners proceeded to pass a resolution endorsing the plan for widening Chardon St. and other thoroughfares. They agreed that widening Chardon Street, and developing the West End more broadly, would increase property values and provide a satisfactory location for “warehouses and wholesale concerns that have business interests north of Boston,” according to the Globe.

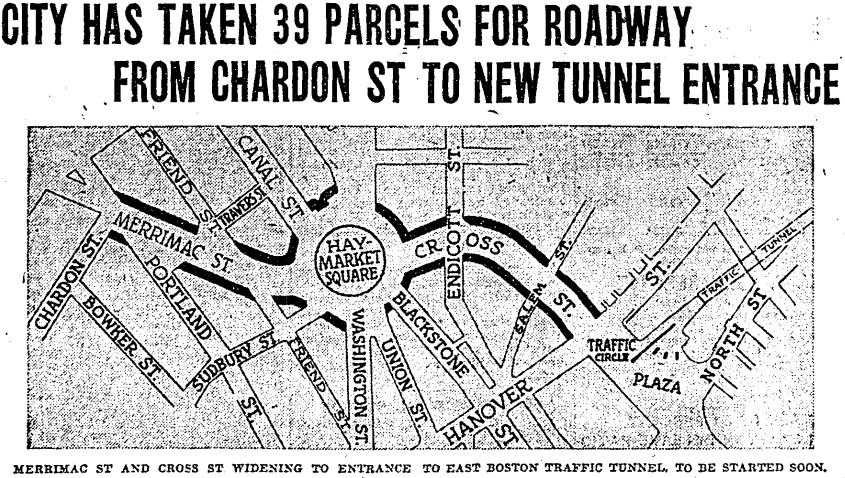

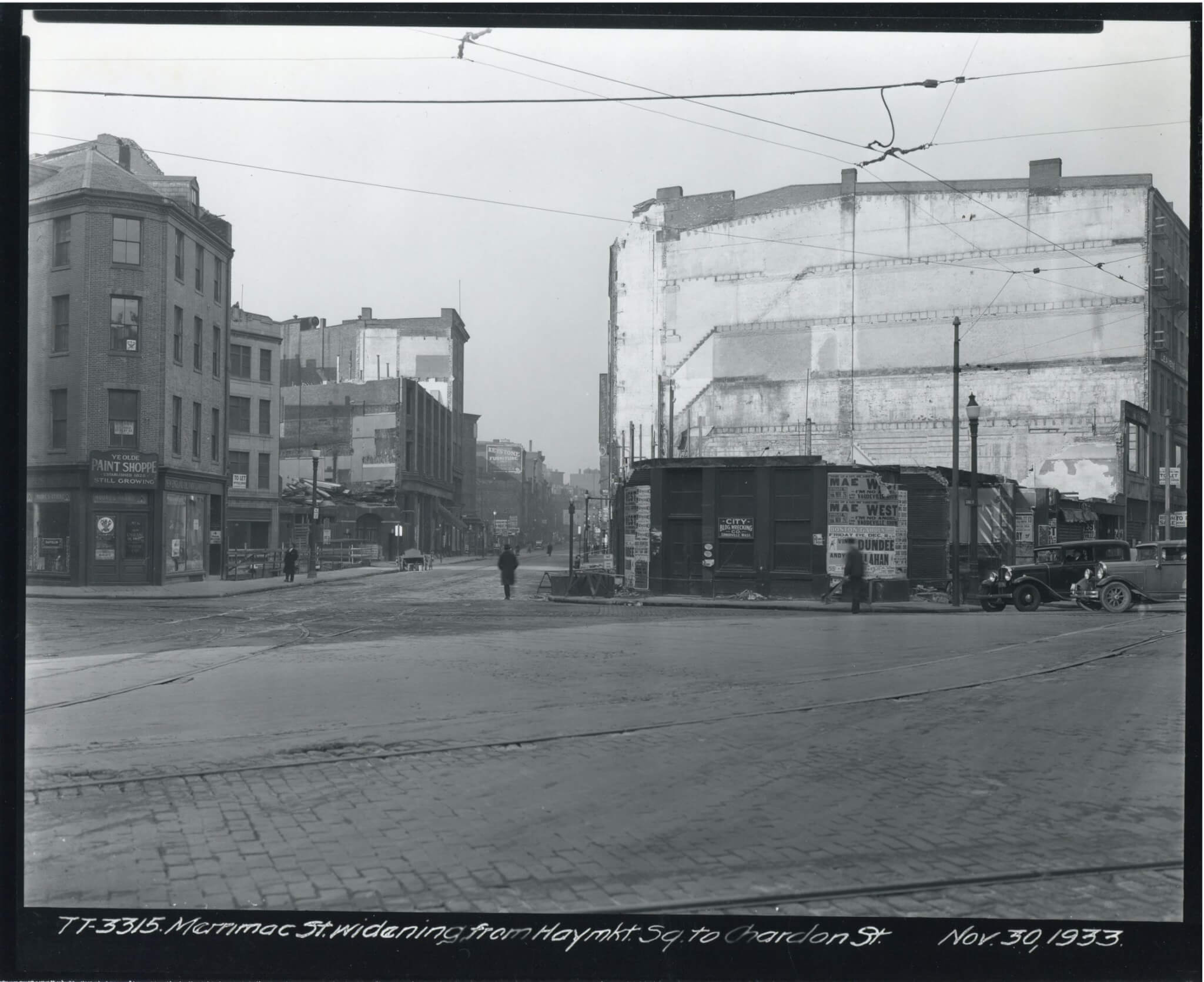

Momentum for widening Chardon Street picked up in the state legislature, though not without controversy. In 1932, the State Senate adopted an amendment to uphold the constitutionality of a bill permitting Boston to borrow $3,000,000 to widen Haymarket Square and the adjacent streets for the purpose of expanding approaches to the East Boston tunnel. One of the strongest opponents to the amendment was Senator Henry Parkman, Jr., who called the bill “street widening camouflage.” He insisted that the bill “can no longer, under a camouflage, be considered as connected with the East Boston tunnel,” and that proponents had ulterior motives. “Someone behind this bill,” Parkman argued, “must be interested in property on Chardon St., because property on that street will have to be taken to make the widening of Merrimac St. possible.” The state legislature ultimately authorized the $3,000,000 appropriation in 1933, and Mayor Curley announced on June 1, 1933 that the city took 39 parcels by eminent domain in order to carry out the new street designs. On November 29, 1935, the Street Commissioners passed a resolution commending the widening of Chardon Street as a “public improvement.”

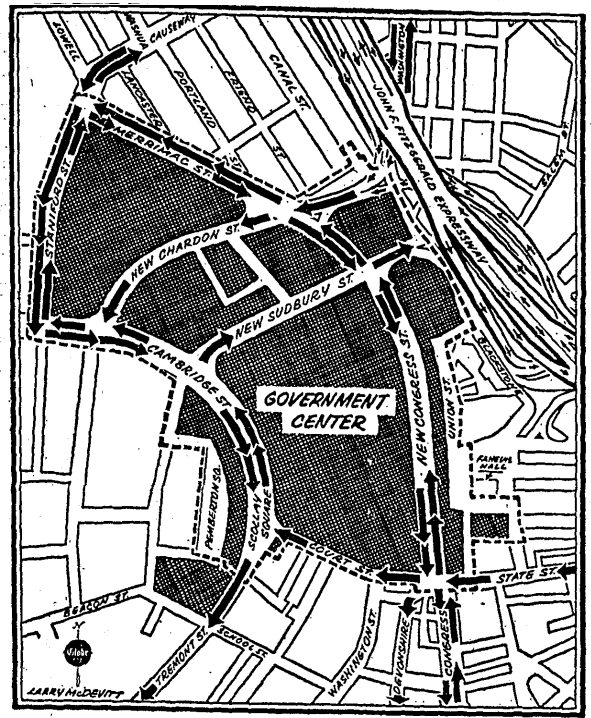

Chardon St. was renamed New Chardon St. during the implementation of the “Government Center Urban Renewal Plan,” conceived by I.M. Pei & Associates, from 1961 to 1968. The replacement of Scollay Square with Government Center involved city planners redesigning the streets with the intention of reducing traffic congestion; New Chardon Street became a one-way, westbound street, and comprised one half of an east-west corridor with New Sudbury Street. New Chardon Street was once again made wider, and a two-way street, during the Big Dig.

While many influential figures in government and business were involved in the widening of Chardon Street during the 1930s, the role of ordinary West Enders in making their voices heard, speaking to the Mayor directly, was equally impactful.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (“West End Residents Ask Street Widening,” August 21, 1930, page 3; “Thoroughfare Plan Receives Support,” January 9, 1931, page 34; “Central Artery Plan Indorsed [sic],” March 5, 1931, page 7; “City Has Taken 39 Parcels for Roadway from Chardon St. to New Tunnel Entrance,” June 2, 1933, page 37; “Mayor Says City Would Gain on Perkins-St Deal,” February 7, 1936, page 16; “City Garage to Ease Government Center Traffic,” December 24, 1961, page 19)