An Appeal for Children's Recreation and Community-Led Development in the 1930s West End

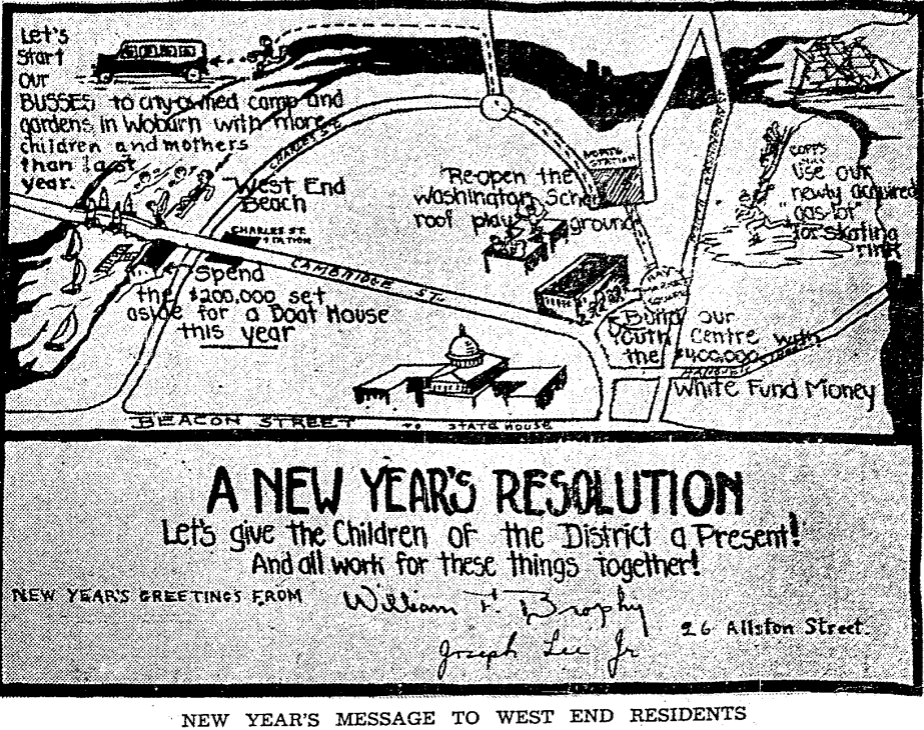

In 1937, ten-thousand West Enders received a creative New Year’s greeting card demanding improvements in children’s recreational opportunities, from William F. Brophy, a lawyer who worked in the West End, and Joseph Lee, Jr., the son of the “Father of the Playground Movement” in America.

Just before January 1, 1937, ten-thousand residents of the West End (about 75% of the neighborhood’s population in the 1930s) received a New Year’s greeting card from William F. Brophy, a lawyer who worked in the West End yet lived outside the neighborhood on 26 Allston Street, and Joseph Lee, Jr., chair of the West End Joint Planning Committee and the Outdoor Recreation Committee of Massachusetts. Brophy had “for some time evidenced an interest in the welfare of West End children,” according to the Globe. And Lee’s father, Joseph Lee, Sr., was considered the “Father of the Playground Movement” for his influential role in developing experimental urban playgrounds based upon his studies of children and play. The greeting card proposed a New Year’s resolution for the West End community to work collectively toward improving recreational facilities for the neighborhood’s children. More than a set of words, the card featured a hand-drawn sketch of the West End with text and images representing Brophy and Lee’s five proposals. Each of those were clarified in a public statement by Brophy and Lee, which the Globe recorded on New Year’s Day in 1937.

Leading the proposals was a demand for the City Council to appropriate money for buses to send children to the Babylon Hill estate in Woburn. On November 18, 1925, Mary Cummings donated the estate to the City of Boston so that her 200 acres of land could be used as a park and camp for Boston residents to take a short vacation. The City Planning Board approved Cummings’ gift with resounding praise for how it “opens up unusual opportunities for recreation and health,” and asked for immediate implementation of the park “in keeping with Ms. Cummings’ desire ‘to give health, happiness, and a fuller life to the busy people of Boston.”” Babylon Hill was located ten miles from the city yet accessible by a state highway, and this made the park accessible, the Board observed, with the emergence of “the rapidly developing bus system.” Yet Brophy and Lee argued that Boston was not investing enough resources into transporting an adequate number of children to the city-owned park. They noted that just 200 children from the North End were bussed to Babylon Hill in 1936, when it would be viable to send 2,000 children every week, from neighborhoods including the West End, by bus.

The additional proposals called for improvements within the West End itself. Brophy and Lee demanded that the Metropolitan District Commission finally build a boathouse at the West End Beach with the $200,000 it already set aside for said boathouse in 1932. Their greeting card also asked for a playground to be constructed on the rooftop of the Washington School, then closed up, on Norman Street. The building where students formerly attended the Washington School then housed the offices of the Department of School Buildings, but Brophy and Lee argued that this department’s work would not be disrupted by using the building’s “10,000 square feet of unused space” for recreation. The greeting card had also called for a new youth center built with $400,000 from the city’s George Robert White Fund (created in 1922 from White’s donation to fund “works of public utility”), and for creating a new ice rink by flooding the “Gas Lot Playground” on Prince and Snowhill Streets.

The most significant aspect of Brophy and Lee’s activism towards improving recreation was their community-led vision of urban planning. In their public statement accompanying the card, they concluded that “the same groups, involving most of the local clubs of the neighborhood through the Planning Committees and the Youth Center Conference, have been pushing forward these projects, making the program of neighborhood improvement a community one, with the people all taking part.” The scale at which William Brophy and James Lee, Jr. engaged with public discussions of urban planning, through community groups and a message to three-quarters of the neighborhood, reveals a unique and creative method of responding to, and validating, West Enders’ genuine need for youth recreational opportunities in the 1930s.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: ProQuest/Boston Globe (“New Year’s Greeting Card Sent to 10,000 Urging West End Recreational Facilities,” January 1, 1937, page 20), City of Boston (George Robert White Fund), “The Story of the Joseph Lee Memorial Library and Archives,” Annual Report of the City Planning Board, 1925 (Google Books); West End Museum (“Population Over Time in the West End”)