Boston's Ropewalks

A digital reframing of “Ropewalks of the West End and Beyond”, an 2012 exhibit designed and written by Duane Lucia and Tom Burgess.

From it’s earliest days until the late 19th century, Boston’s economy was predominantly a maritime affair, but when the puritan’s arrived in 1630, they did so with a different plan – to recreate the economic model of the Spanish imperial holdings in the Americas. The Puritans intended to mine, process and export the precious metals of New England to Europe. That plan hit a snag, however, when there were no precious metals to be found.

For a little more than a decade, the early Bostonians worked to find an alternative to mining. Eventually one presented itself, the carrying trade, in which Boston’s embryonic merchant elite began a series of disorganized enterprises that would develop into the infamous Triangle Trade, as well as the China Trade and many lesser-know trade routes.

From that point on, shipping was the key to economic success in Boston, and since shipping required ships, naval supplies – wood, cordage, caulking, and the like – became critical to the success of the city.

Establishing an Industry in the Colonial Era

Until 1640, the Massachusetts Bay Colony relied on Great Britain to supply the majority of its finished goods. Any rope or twine that was produced in the colony had to be made with locally grown flax or hemp, and was most likely produced by families for their own use with any excess being sold locally.

In 1638 the Boston area’s first “ropefields” were established in Charlestown. “Rope-maker’s Lane” ran along the town’s colonial waterfront, which is now the cite of City Square and Lynde Street. Soon Boston would have it’s own ropemakers and shipbuilders.

By 1642 shipping and its constituent industries were expanding significantly in Boston. The English Civil War reduced immigration and support from the mother country and limited imperial oversight. As a result, colonists were able to establish their own trade routes to other colonies, and even foreign nations, for the first time. These gains were further solidified during Queen Anne’s War in 1709, confirming Boston as a leading port in Colonial America.

The First Ropemakers

- Nehemiah Bourne

- John Harrison

- John Heyman

- William Tilly

- James Barton

- Stephen Minot

- Theodore Atkinson

- Edward Gray

- Edward Carnes

In 1641 the shipbuilder Nehemiah Bourne came to Boston on a special permit from England and launched the Trial, Boston’s first merchant vessel. The 160-ton ship carried goods from Boston to the Azores and West Indies. Three years later he returned to England to fight in the English Civil War.

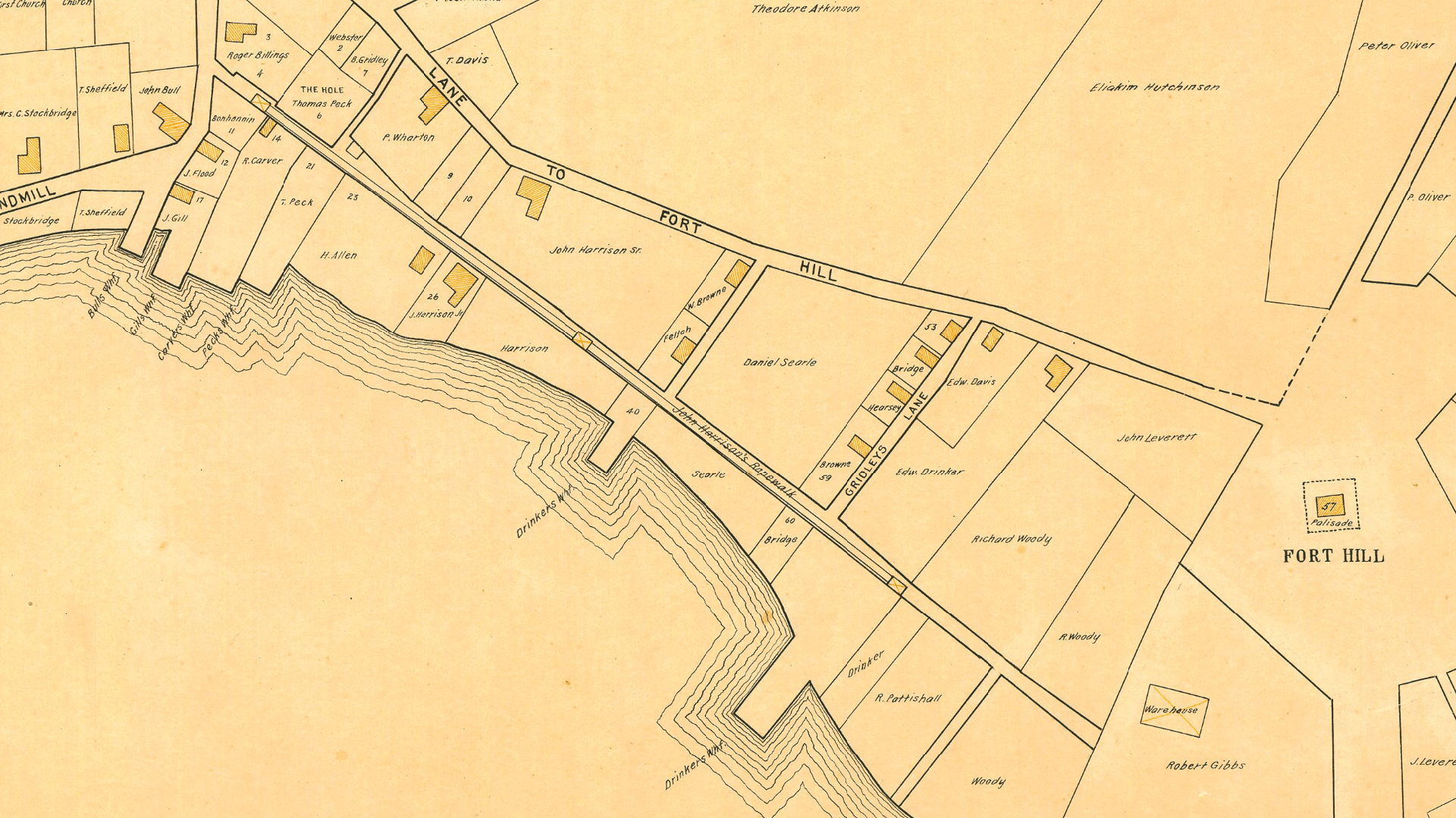

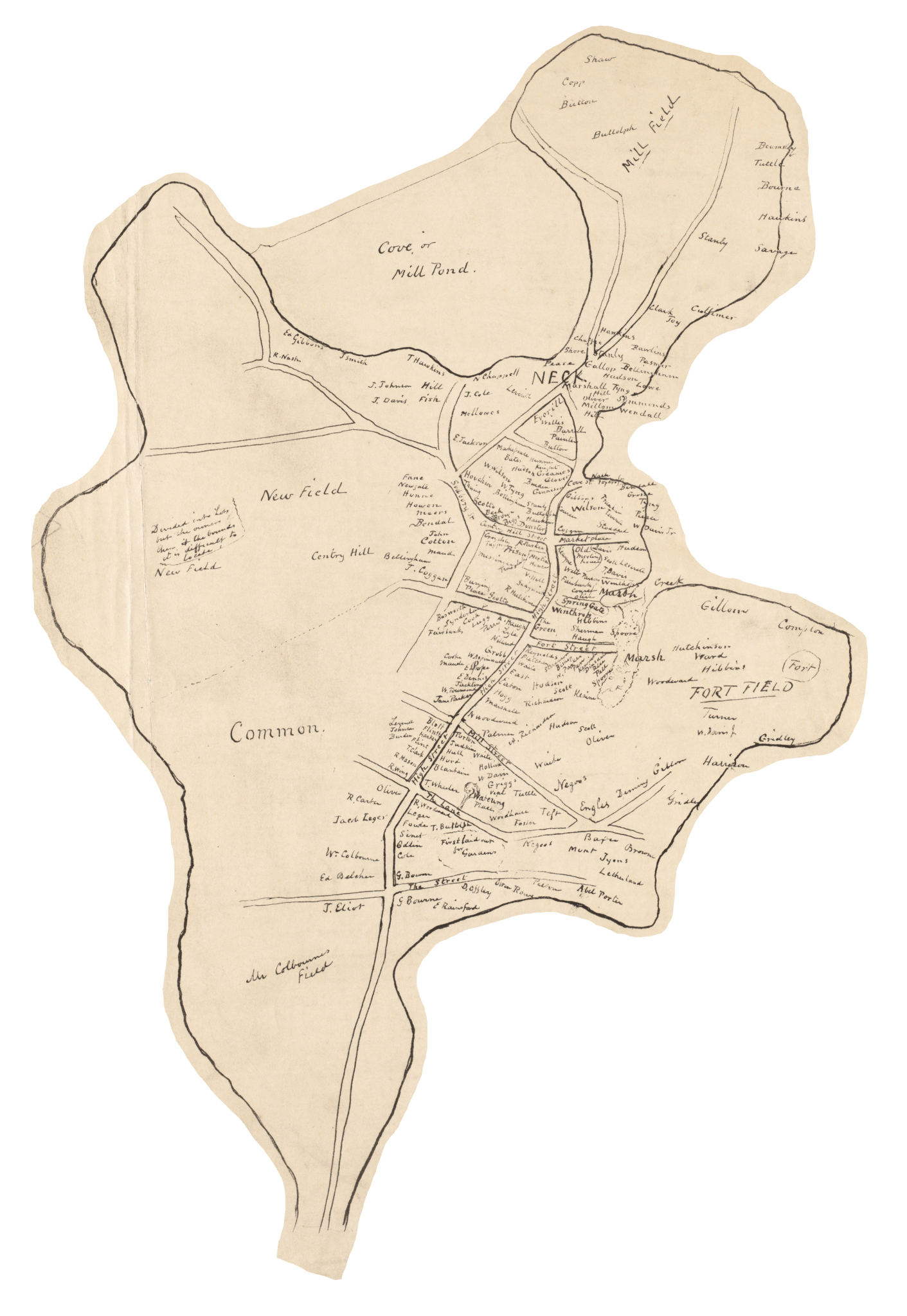

In 1642 John Harrison was invited to Boston to establish a cordage business. In 1666 he had acquired additional land and built a 984 foot long ropewalk. Clough’s reconstructed map of Boston in 1673 shows Harrison’s ropewalk running along modern-day Purchase Street.

Twenty years after it’s construction, in 1685, Harrison sold a 1/3 interest in his ropewalk, including the tar-house and warehouse, to James Barton.

In 1662 John Heyman received a license to produce fishing lines in Boston, but a year later he was ordered to stop producing rope and moved to Charlestown.

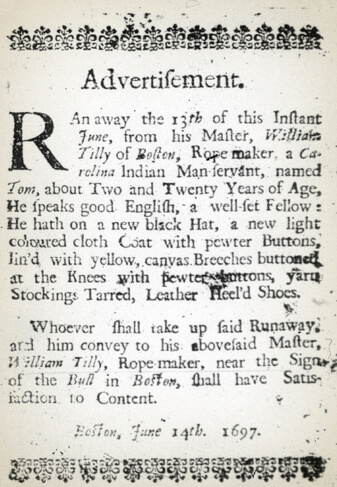

By 1697 at least one more ropemaker was running a successful business in Boston. Mr. William Tilly had the resources to hold slaves, and when one of them, Tom, escaped in June of 1697, Tilly advertised for his return with the promise that any would-be slavecatcher would “have Satisfaction to Content (sic).”

Tilly remained involved in the ropemaking industry into the 18th century. In 1705 he seems to have taken full control of the Harrison walk, which had moved from it’s previous location to the area between modern day Atkinson and Pearl Streets. Two years later, records show Tilly building 3 workhouses and a “shedd (sic) of 100 fathoms long and 11 foot wide”.

In 1700, James Barton set up a ropewalk on land he was renting from the Leverett family in the New Fields (now the West End). The area became known as Barton’s Point, as it is marked on Bonner’s map (below).

Around 1700, Stephen Minot set up a ropewalk on the north slope of Beacon Hill at Ridgeway Lane.

The namesake of Atkinson Street, Theodore Atkinson operated a ropewalk parallel to William Tilly’s in 1705.

In 1705 Edward Grey owned a ropewalk parallel to William Tilly and Theodore Atkinson’s. In 1712 he improved his facilities with a range of wood sheds 400 feet long.

In 1771 at least one more ropewalk stood in the historic West End (in the area then, and now once more, included in Beacon Hill). Edward Carnes is recorded purchasing a ropewalk on Joy Street in that year, which had begun operating sometime after 1743.

Boston c. 1640

A rough and inaccurate sketch of the streets of Boston as they are supposed to have been first laid out & the owners of the soil, from 1630 to 1650 or thereabouts (Map by William Appleton, Boston Public Library)

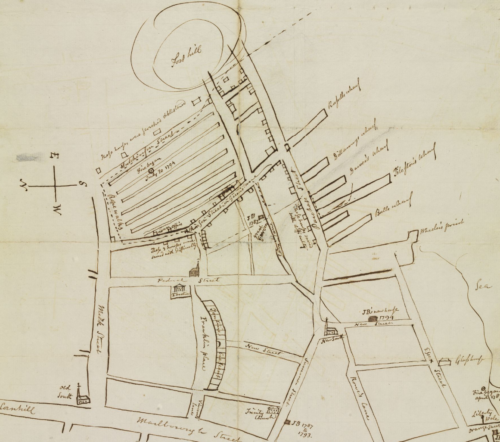

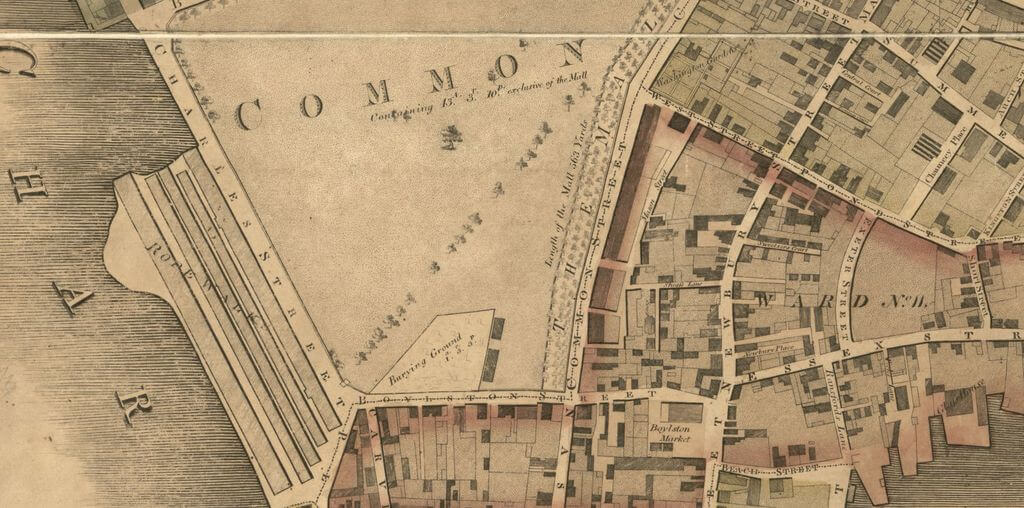

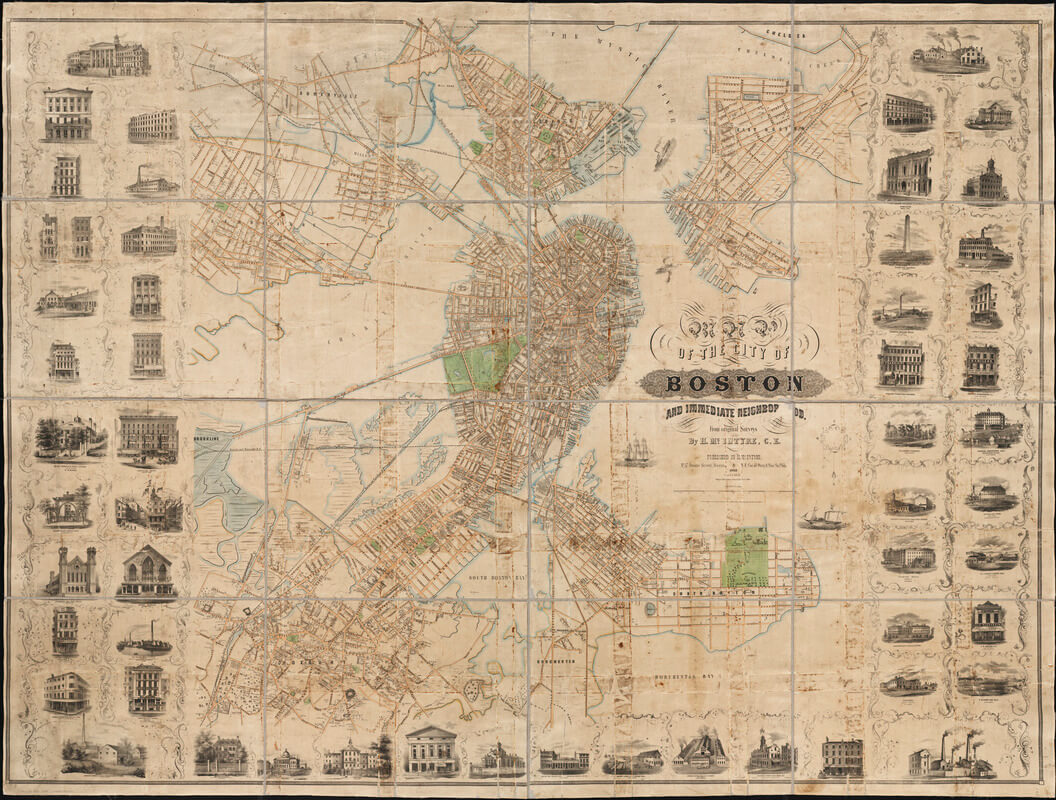

Boston c. 1730

The town of Boston in New England by John Bonner, 1723-33 (Boston Public Library)

The ropemaking industry continued to expand between the 1730’s and the Revolutionary War. By 1743 two additional ropewalks were added to William Prince’s edited version of the Bonner Map, and later maps show seven operating in the area by 1790.

Ropewalks and Revolution

In 1770, Boston’s ropewalks became one of the many places where resistance to the Crown developed into a fledgling revolution. Scuffles broke out between British soldiers and workers at the Atkinson Street ropewalks. Soon after, ropewalk workers took center stage in the Boston Massacre. Samuel Grey and Crispus Attucks were both ropewalk workers killed in the Massacre, and other workers including Jeffery Richardson and John Gray also participated in the affair.

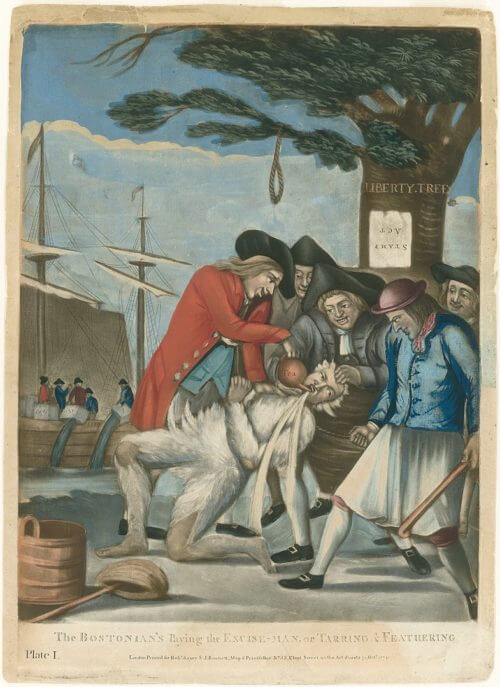

The practice of tarring and feathering provided another intersection between the ropewalks and the revolution. The tar used in these mob attacks, which could leave severe burns that occasionally led to death, came from the city’s ropewalks. The feathers were commonly taken from household pillows, sometimes ones stolen from the afflicted person’s home.

Ropemaking in the Federalist Period

Despite numerous challenges posed by conflicts with France and Great Britain, Boston remained a major port into the latter half of the 19th century. As it’s ships circled the globe, the city’s ropemakers continued to supply the cordage required for naval vessels.

Unfortunately for Bostonians, ropemaking came with some serious drawbacks. The ropemaking process involved keeping hot tar – and corollary open flames – in the presence of numerous airborne hemp fibers. These fibers were constantly at risk of igniting, as they did at one of the Pearl Street walks on July 30, 1794. After the fire, six of the seven Pearl Street ropewalks relocated to filled land at the eastern end of the Boston Common on what is now the Public Gardens. The seventh, owned by John and Samuel Gray, moved to Charlestown. Two years later a ropewalk on the Charles owned by MacNeills burned, and that business moved to Charlestown as well.

Fires continued to threaten Boston’s ropemaking industry throughout their history, and are recorded burning ropewalks at least three times between 1795 and 1824 alone.

Despite the fires, in 1798 Boston could claim more than a dozen ropewalks, including 5 on Charles Street (Public Garden), 3-5 on Beacon Hill and another 3 on Allen Street. The Ridgeway Lane ropewalk seems to have survived to the end of the century as well, along with one on South Russell Street.

Mapping Ropewalks at the Turn of the 19th Century

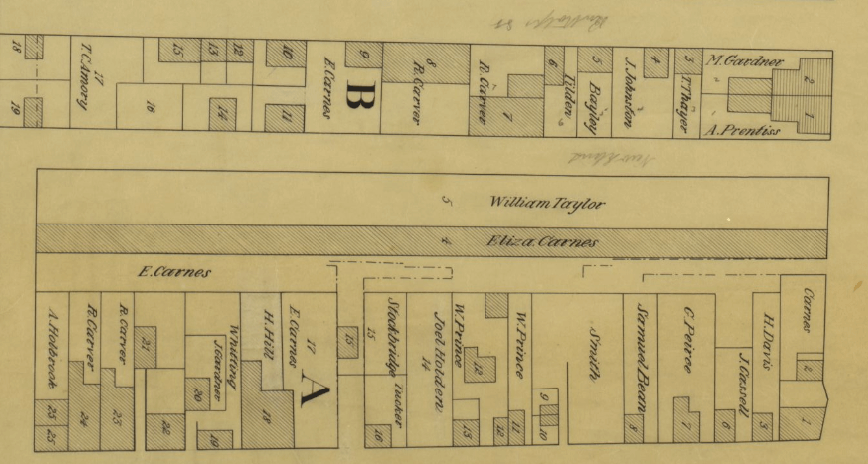

Above 3 ropewalks are visible along the future Myrtle Street operated by the Austin brothers, the Cade brothers, and Joseph Carnes. Related ropemaking operations were carried out by the Austins and Aniope Boynton on lots east of the ropewalks.

These ropewalks were sold to residential developers in 1805.

Along (modern) South Russell Street, William Taylor and Elizabeth Carnes owned a pair of ropewalks. Taylor held a second walk along Allen’s highway, and Elizabeth, who had inherited the ropewalk from her deceased husband, likely left hers to the operation of Joseph Carnes, who owned another walk on Beacon Hill.

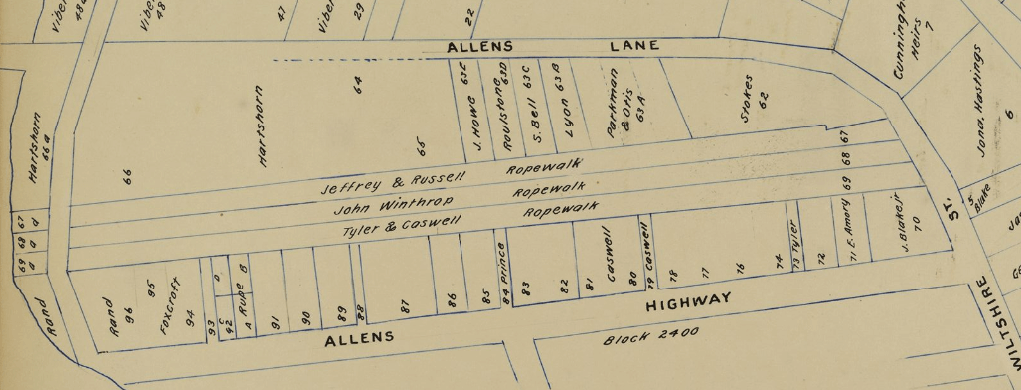

Three ropewalks remained in West Boston (formerly the New Fields, modern West End) in 1798. They were owned by Tyler and Caswell, John Winthrop, and Jeffreys and Russel, respectively. Jeffreys and Russell produced the anchor cable for the USS Constitution in 1797.

The West Boston ropewalks were sold to residential developers in 1807.

The plots owned by the Austins on this map are likely the ropewalk formerly owned by Samuel Waldo. The lot owned by Taylor between George (Hancock) and Belknap (Joy) Streets may have been a warehouse used to store hemp and rope.

After the Great Fire of 1794, 6 ropewalks were established on Charles Street across from the Boston Common on filled land that is now part of the Public Garden. This group of ropewalks suffered a fire in 1806, but survived as the last operational walks in Boston in 1815. In 1819, however, 3 successive fires and the Panic of 1819 effectively ended the viability of the ropewalks on Charles Street.

A Declining Industry in the Industrial Age

Despite ambitious efforts, Boston’s ropewalk industry was unable to survive a mix of national consolidation and the decline of sailing vessels. While the city continued to house multiple ropewalks until the end of the 19th century, and a single walk survived until 1975, the industry steadily declined from the 1820s until its extinction.

By the 1830s there were no longer ropewalks in Boston’s traditional downtown. The walks that remained occupied landfill areas in the Back Bay and Fenway. Eventually the Charlestown Navy Yard held the last surviving walk in Boston (after Charlestown was incorporated into the city in the 1870s).

The McIntyre map of Boston shows how the Back Bay residences were marching steadily toward the fens and the Mill Dam, from which the Boston Hemp Manufacturing Company was constructed. A number of other walks are also visible. (Boston Public Library)

The Last Walks in Boston

The Boston Hemp Manufacturing Company occupied a site on the engineering masterpiece that was the Back Bay Mill Dam starting in 1831. The only mill dam in history to be capable of operating 24 hours a day, the Back Bay Dam was never fully utilized due to the combined challenges of encroaching railroads and rising prevalence of coal. The ropewalk and other mill-powered factories operated for only a few decades before they were replaced by Commonwealth Avenue and the rest of the Back Bay.

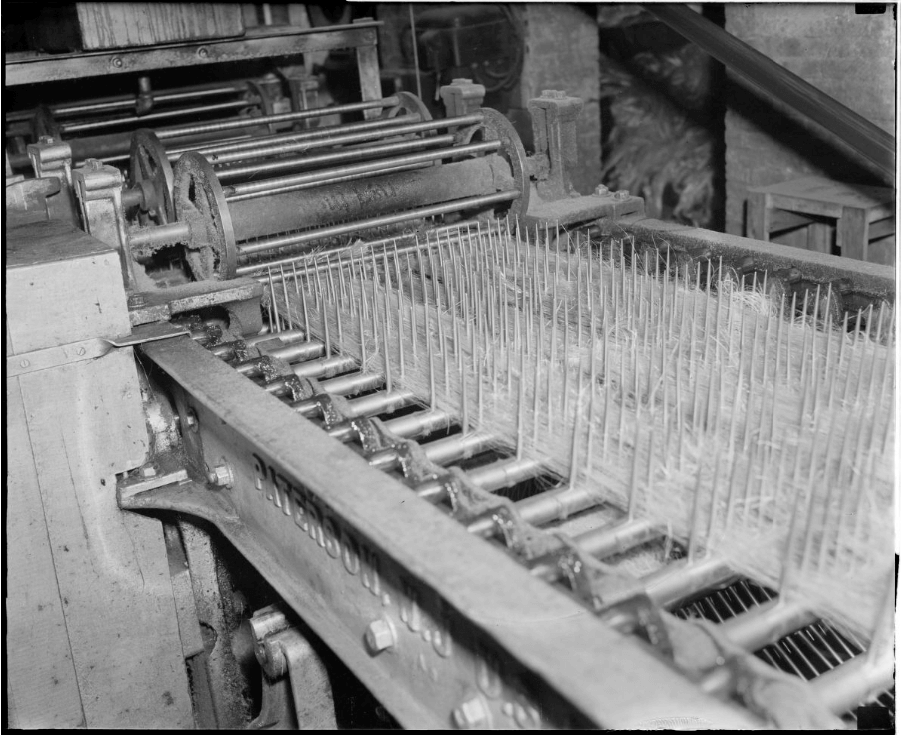

The inventor Daniel Treadwell’s mechanized ropemaking machines were first implemented at this site after successfully creating the machine in 1829. Mechanisms capable of spinning 1,000 tons of cordage a year were installed at the Back Bay site.

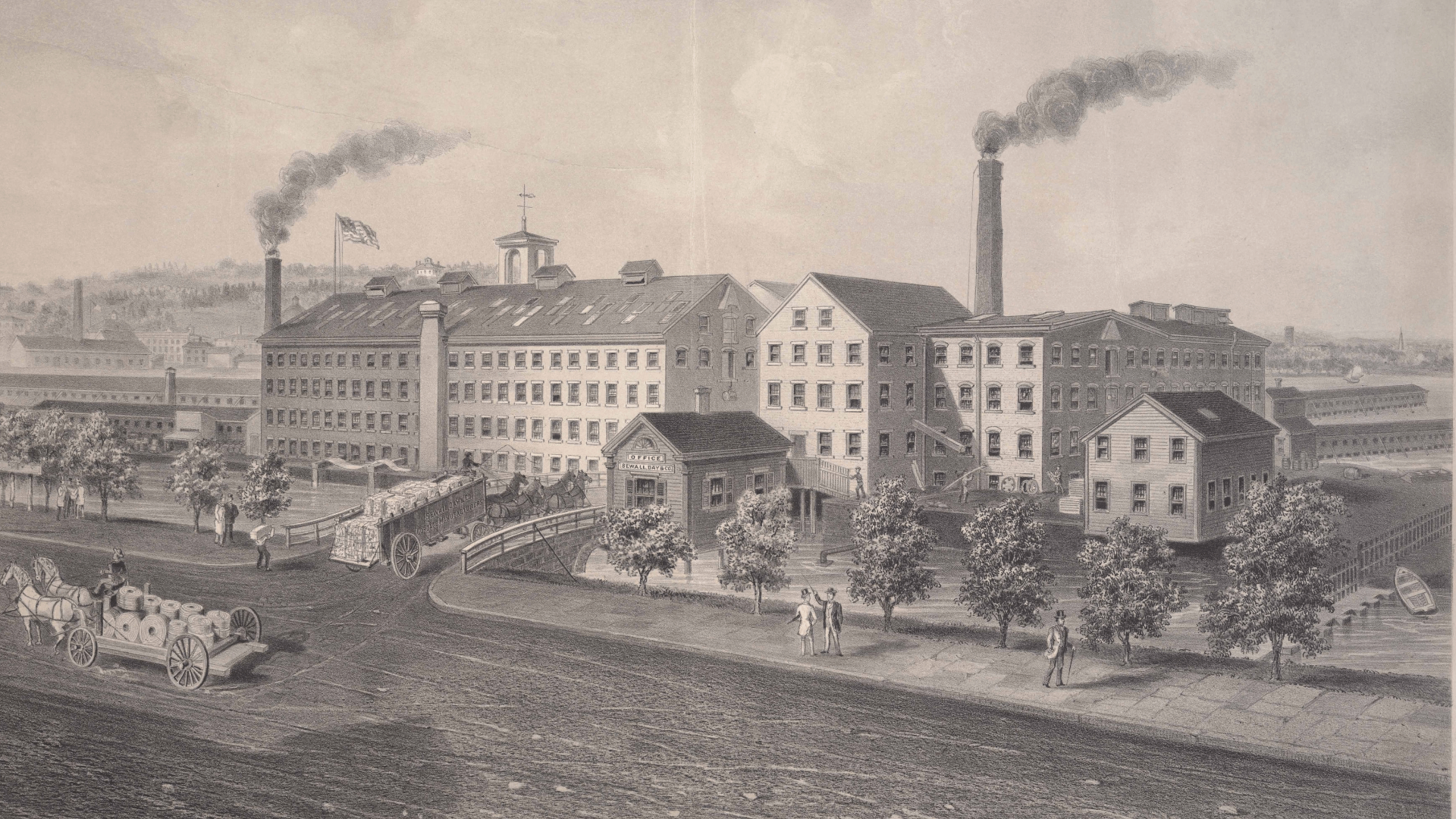

In 1835 the Sewall and Day Cordage Company opened on the site of Wentworth Institute and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Six years later Moses Day adopted the spinning jenny for cordage use, an improvement on Treadwell’s mechanization system. The company survived until 1890, when it was taken over by National Cordage Company, an attempted monopolistic venture based out of New Jersey that collapsed during an 1895 recession, closing the Fenway walk. Most of Boston’s other ropewalks underwent a similar takeover and failure with National Cordage, only two private walks – Pearson and Plymouth Cordage – survived past 1895. Plymouth Cordage continued to operate until 1970, serving as America’s premier fabricator of rope for much of that period.

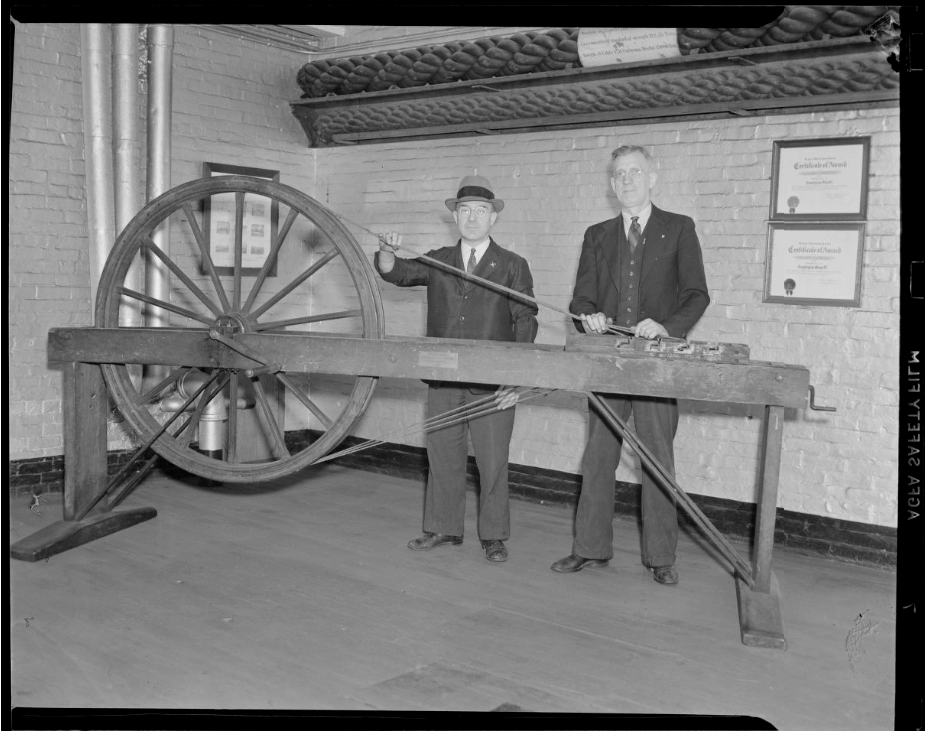

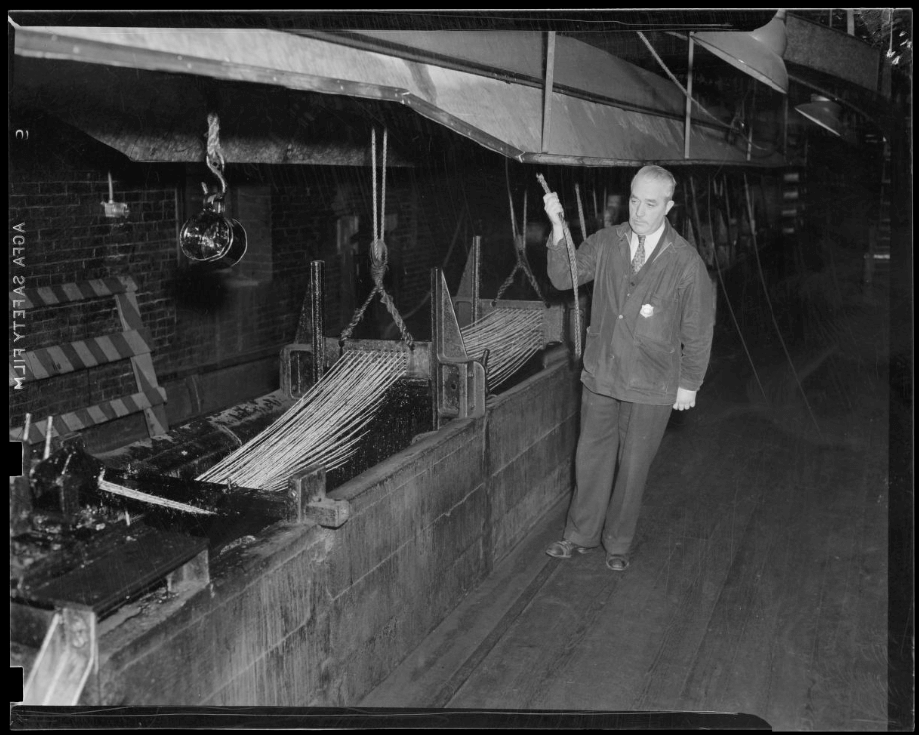

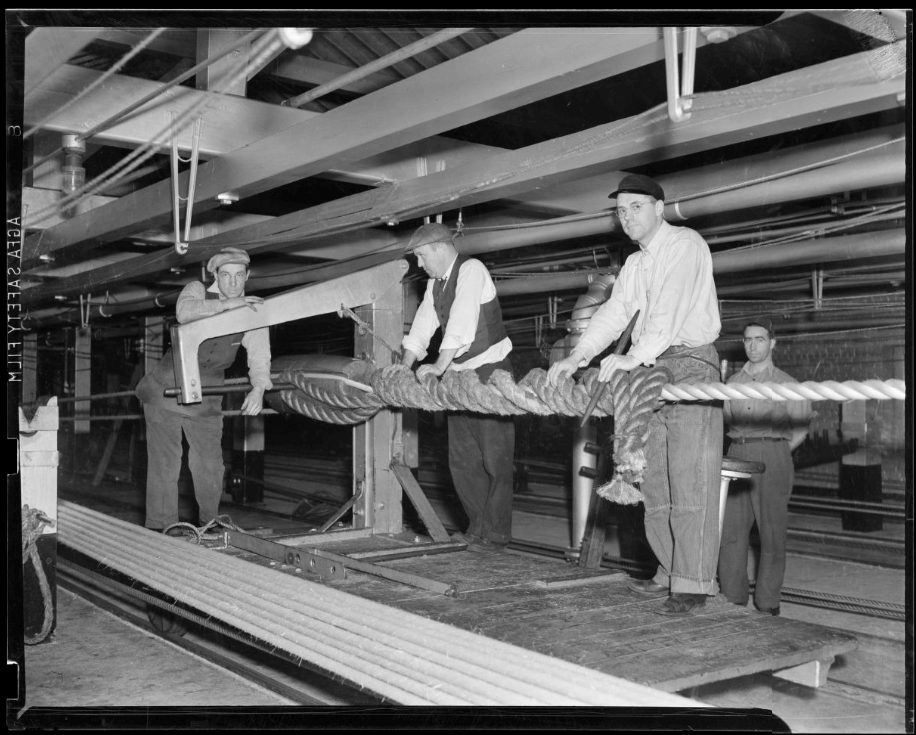

Between 1834 and 1837 Alexander Parris designed and built the ropewalk at Charlestown Navy Yard. The immense granite structure was the principle manufactory of rope for the US Navy from its completion until 1950, and held a complete set of machines designed by inventor Daniel Treadwell. Along with Plymouth Cordage, this ropewalk was one of the first factories to employ women.

Despite a 1880 fire, The Charlestown Navy Yard Ropewalk operated at or near capacity until 1950, when production was reduced to a minimum. Twenty-five years later, in 1975, the walks were permanently closed. The building retained its machinery for decades, but a fire in 2002 made use as a historical landmark challenging (despite it being the only complete ropewalk in the US). In 2021 the building began undergoing conversion into residential units – with a public exhibit meant to highlight the structures historic significance.

- Back Bay

-

The Boston Hemp Manufacturing Company occupied a site on the engineering masterpiece that was the Back Bay Mill Dam starting in 1831. The only mill dam in history to be capable of operating 24 hours a day, the Back Bay Dam was never fully utilized due to the combined challenges of encroaching railroads and rising prevalence of coal. The ropewalk and other mill-powered factories operated for only a few decades before they were replaced by Commonwealth Avenue and the rest of the Back Bay.

The inventor Daniel Treadwell’s mechanized ropemaking machines were first implemented at this site after successfully creating the machine in 1829. Mechanisms capable of spinning 1,000 tons of cordage a year were installed at the Back Bay site.

- Fenway

-

In 1835 the Sewall and Day Cordage Company opened on the site of Wentworth Institute and the Museum of Fine Arts Boston. Six years later Moses Day adopted the spinning jenny for cordage use, an improvement on Treadwell’s mechanization system. The company survived until 1890, when it was taken over by National Cordage Company, an attempted monopolistic venture based out of New Jersey that collapsed during an 1895 recession, closing the Fenway walk. Most of Boston’s other ropewalks underwent a similar takeover and failure with National Cordage, only two private walks – Pearson and Plymouth Cordage – survived past 1895. Plymouth Cordage continued to operate until 1970, serving as America’s premier fabricator of rope for much of that period.

- Charlestown

-

Between 1834 and 1837 Alexander Parris designed and built the ropewalk at Charlestown Navy Yard. The immense granite structure was the principle manufactory of rope for the US Navy from its completion until 1950, and held a complete set of machines designed by inventor Daniel Treadwell. Along with Plymouth Cordage, this ropewalk was one of the first factories to employ women.

Despite a 1880 fire, The Charlestown Navy Yard Ropewalk operated at or near capacity until 1950, when production was reduced to a minimum. Twenty-five years later, in 1975, the walks were permanently closed. The building retained its machinery for decades, but a fire in 2002 made use as a historical landmark challenging (despite it being the only complete ropewalk in the US). In 2021 the building began undergoing conversion into residential units – with a public exhibit meant to highlight the structures historic significance.

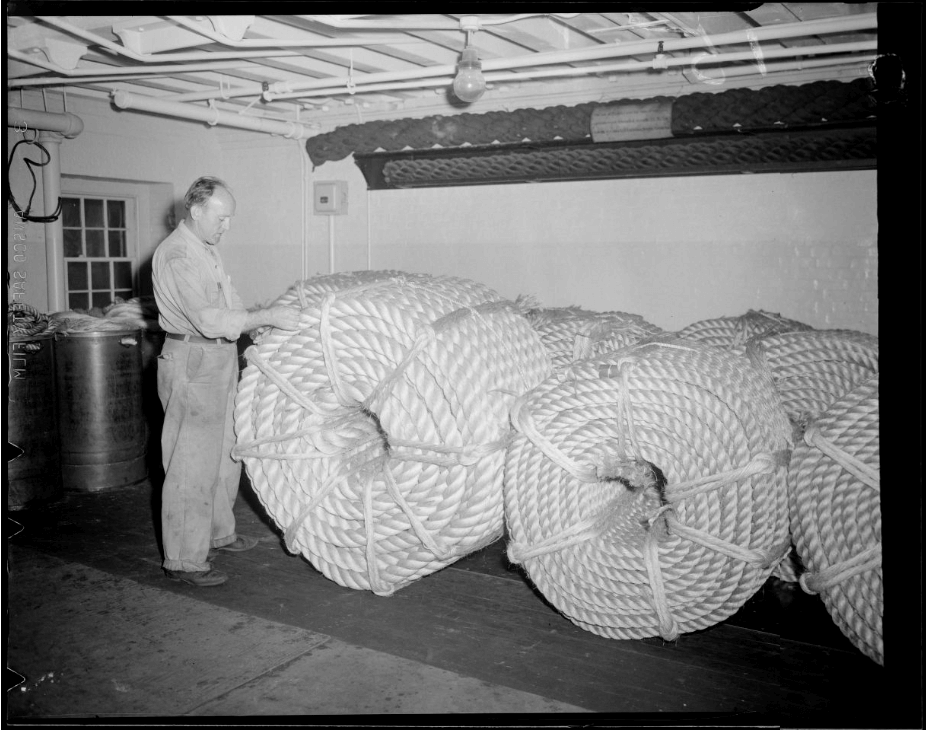

Making Rope at the Charlestown Navy Yard

Article by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: Ropewalks of the West End and Beyond, Lucia and Burgess, The West End Museum; Boston Public Library Leventhal Collection