Dry Goods Stores in the West End

The West End’s dry goods stores provide valuable insights into the economic activity of the neighborhood. With data sourced from Boston Business Directories and Barry Oshry – the son of one of the West End’s most well-known dry goods business owners – providing insights on his family business, this report explores how one of the most essential industries in industrial America fared in the West End.

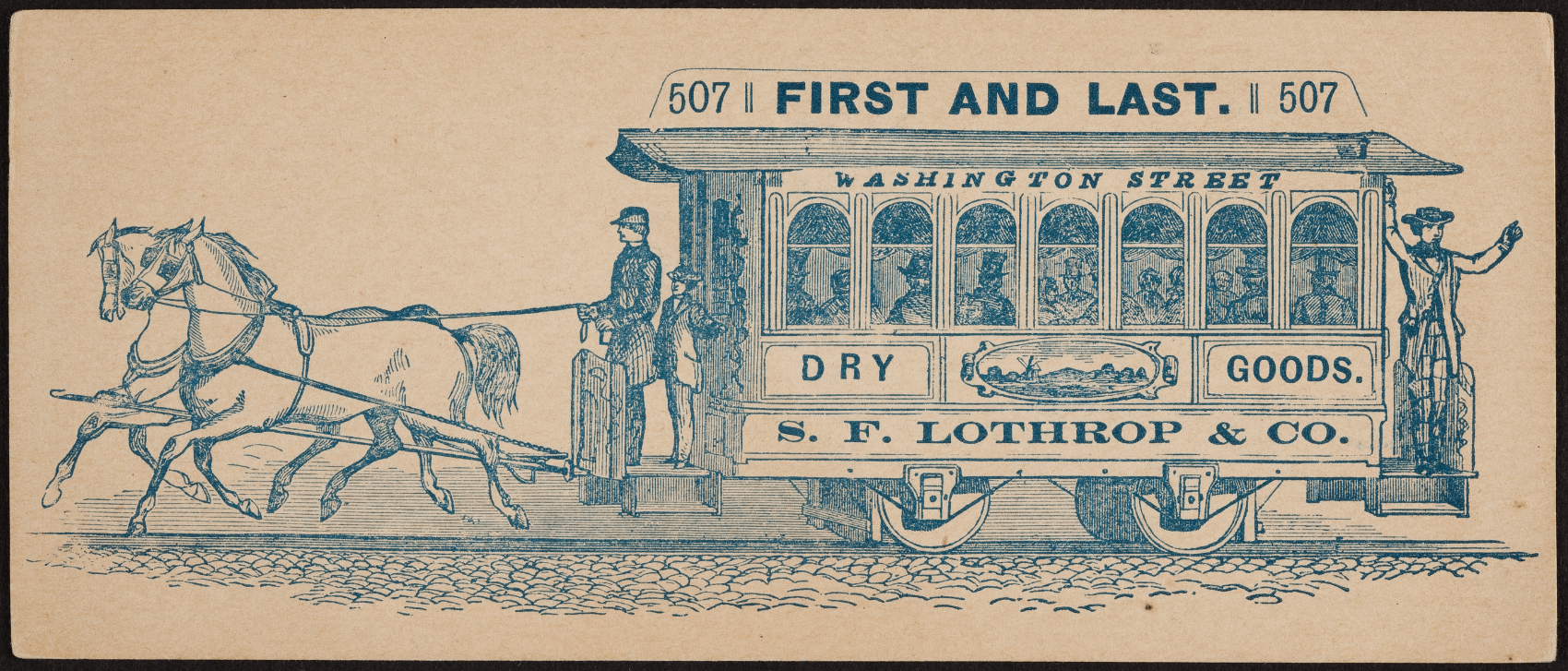

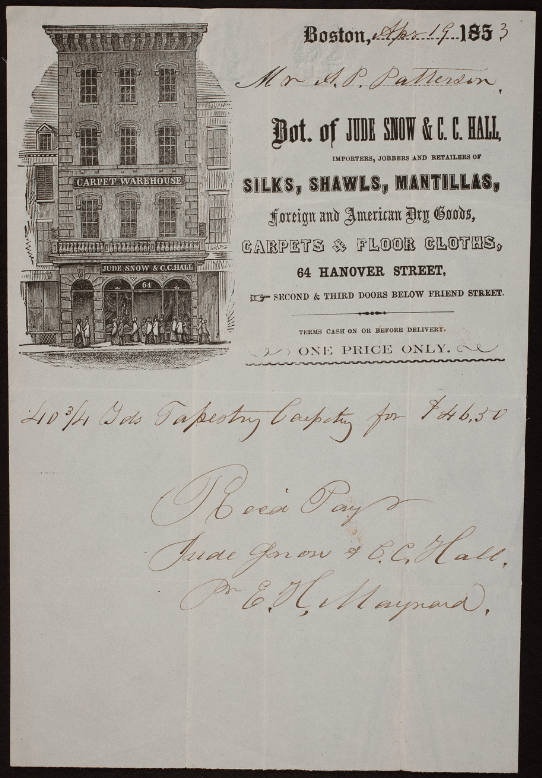

No 19th century shopper could live without a dry goods store, where linens, dry food items like coffee beans or jerky, and other household products were sold. A hallmark of frontier outposts and urban centers alike, the storefronts dotted the American landscape providing key consumer goods from the late colonial era well into the 20th century.

Boston City directories dating back to 1850 document the presence of these stores in the West End. With burgeoning textile mills 50 miles west in the Blackstone Valley, and a growing immigrant population, these largely family-owned enterprises connected the area’s goods to its citizens.

Immigration en masse to Boston began after the potato famine struck Ireland in 1846. By 1850, 23 dry goods stores dotted the West End, ranging from the North slope of Beacon Hill to Tremont Row in the area which would eventually become Scollay Square (now Government Center). A decade later, 25 stores were counted in the neighborhood. At least 10 of the shops had been in business for over a decade, appearing in both the 1850 and 1860 Business Directory. At the time, 1 in 5 stores were listed under a women’s name – one woman, Sarah May Wells, operated her store (on W. Cedar and then on Leverett Street) for over 20 years.

Eighteen dry goods stores were recorded in the West End in 1870. Several years later, the Panic of 1873 created nationwide turmoil and resulted in 65 straight months of economic contraction. In the winter of 1873, Boston citizens protested the poor economic conditions in large demonstrations. Correspondingly, fewer stores were recorded in following years with only 6 in 1879 and 10 in 1896.

As the country recovered economically, immigrant families continued to settle in the West End – the neighborhood population swelled to 34,500 by 1900. By the turn of the 20th century, dry goods stores had recovered, and there were 27 in the neighborhood. New ventures were common, alongside a handful of longstanding ones. When Hiram N. Stearns closed his store on 17 Leverett Street sometime between 1896 and 1900, his store was the last to have been operating continuously from 1850. By this time, shops appeared more frequently in the Upper End (later targeted for redevelopment, this area is now Charles River Park). As strong neighborhood identities tied to ethnic background formed in the West End, immigrant entrepreneurs increasingly set up shop in their communities.

When David and Meyer Oshry immigrated from Lithuania to Boston in 1896, they did just that. In 1902, at just 20 years old, the brothers opened Oshry Brothers Dry Goods at 10 Spring Street the Upper End. One of the founding families of the Vilna Shul in Beacon Hill, the Oshry’s were one of several Jewish families that found tremendous success in the West End dry goods business during America’s second immigration wave.

While the West End population began to decline after 1900, the neighborhood’s dry goods industry continued to expand, with 39 businesses operating in the Upper End alone in 1922. Commercial areas developed on Lowell Street and Spring Street, and the newly invented automobile facilitated increased movement of commercial goods from producers to storefronts.

A sharp downtick in dry goods shops occurred between 1922 and 1935 for several reasons. First, the Great Depression ravaged Boston and Massachusetts as a whole. In spring of 1930, conservative estimates indicated 40,000 Bostonians were jobless; the city faced an unemployment rate of 12%. By 1934, state unemployment rate estimates neared 25%, and mill towns throughout the Blackstone Valley were forced to close, leaving textile mill workers without work and stores with fewer goods. Second, the Standardized Zoning Enforcement Act passed by the federal government in 1924 delivered uniform zoning regulations across the country for the first time; they were adopted by Boston in Chapter 488 of the Zoning Acts of 1924. Residential and commercial areas were codified (and separated) for the first time, and the sites of several former and operating dry goods shops along the southern end of Beacon Hill’s W Cedar Street became entirely residential, forcing closure or relocation. While many stores faltered, Oshry Brothers boomed. Barry Oshry recalls that they were “always looking for bargains…just coming up with ideas to scrape a living – they were very good at that”.

In the 1944 Business Directory, only 6 dry goods stores were listed in the West End, 4 of which stood on the commercial corridor on Spring Street. In the post-war era, increased migration from urban to suburban communities continued to reduce both the consumer base and number of business owning families in the neighborhood. In 1950, the number of stores had increased to eight, six of which were located in the 80-acre redevelopment zone designated for demolition by the Boston Planning Board in 1951 and further outlined in a Boston Housing Authority master plan in 1953. The dry goods stores were only a sliver of the West End business community doomed to redevelopment – barbers, grocers, butchers, and countless other businesses were subjected to a similar fate.

Population in the West End decreased sharply after the announcement, as residents relocated to avoid impending eviction. The area over 30,000 people called home in 1900 housed fewer than 8,000 West Enders as the community neared demolition. They were served by 4 dry goods stores in the redevelopment zone and 6 shops in the larger neighborhood in 1957. When eviction letters were mailed in 1958, Oshry Brothers Dry Goods was one of four dry goods stores forced to close its doors. David Oshry had done business at 10 Spring Street for 56 years, the longest running store of its kind in the West End. So how did his shop, in what was deemed by the BHA “the worst parts of the West End” with only “marginal commercial uses” thrive for so long? Barry Oshry credited the store’s success to his father’s unrelenting entrepreneurial endeavors. “Across the street there was…a similar store where the owner could be regularly seen sitting in a chair just spending the time. But my father was a real hustler”.

Oshry’s defied the commonly held belief that economic activity within the West End served minimal purpose outside it. Barry recalled cold-calling motels up Route 1 towards New Hampshire with his brother selling linens, pillowcases, and sheets out of the back of their car. Churches, fire houses, and police stations relied on the shop to rent roulette wheels and purchase prizes for their street fairs and fundraisers to further enrich their communities. The family-owned store even found success as a national retailer, amassing a nationwide mailing list of nursing homes, hospitals, and motels across the country to sell towels, pillowcases, and sheets. The mailing effort was a family affair, wrapping packages and shipping out mail orders from the shop on Saturday mornings. When his Spring Street storefront was demolished during urban renewal, David Oshry continued the mail-order business out of his son’s store in Roxbury.

The dry goods stores of the West End reflected the vitality of the neighborhood itself, operated largely by immigrant families contributing to the strong community dynamics in the area. While their rise and fall loosely followed West End population and economic trends, stories like Oshry Brothers serve as a reminder that neighborhood business impact cannot simply be reduced to a name in a Business Directory or statistic in an urban planning report. “If it weren’t for renewal, they would still be there today,” Oshry added.

Article by Meyer Aviles, edited by Adam Tomasi & Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: “Industrial Revolution: The Big Story”, Blackstone River Valley National Heritage Corridor. https://blackstoneheritagecorridor.org/learning/history-of-the-valley/the-industrial-revolution-the-big-story/; Tomasi, Adam, “West End Population Report”; Adams, George, “Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1850”. Clerk’s office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts; Adams, Sampson, & Company, “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July 1, 1860”. Clerk’s office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts; Sampson, Davenport, & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1870”. Clerk’s office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts; Mauldin, John. “There Are Alarming Economic Similarities Between Now And 1873.” Business Insider. 11/4/2014; Sampson, Davenport, & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1879”. Clerk’s office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts; Sampson, Murdock, & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1896”; Sampson, Murdock, & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July 1, 1900”; Wangsness, Lisa. “Vilna Shul Descendants Honor Their Heritage”, Boston Globe. 12/1/2013; West End 1910 – Global Boston. https://globalboston.bc.edu/index.php/the-west-end/west-end-1910/; Sampson & Murdock, Co. “The Boston Business Directory for the Year 1922”; James, Green R. and Donahue, Hugh Carter, “Boston’s Workers: A Labor History.” Pg. 106, Boston Public Library. 1979; Smiley, Gene, “Recent Unemployment Rate Estimates for the 1920s and 1930s,” Journal of Economic History, June 1983, 43, 487-9, Referenced in “Employment and Unemployment in the 1930’s” by Robert J. Margo; Plate 003 From Boston 1924 Zoning Maps, Massachusetts. Published by City Planning Board in 1924. http://www.historicmapworks.com/Map/US/1567830/Plate+003/Boston+1924+Zoning+Maps/Massachusetts/; R.L. Polk & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1944”; R.L. Polk & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1950”; Simonian, Kane. “West End Project Report. A Preliminary Redevelopment Study of the West End of Boston”. Urban Redevelopment Division, Boston Housing Authority. March, 1953; R.L. Polk & Co., “The Boston Directory for the Year Commencing July, 1, 1957”; Billboard Magazine, January 30, 1937.