John P. Coburn

John P. Coburn, an African-American clothier, participated in and financially supported the abolitionist movement in Boston. He later ran a gambling house out of his home on Phillips Street, one of the sites of the Black Heritage Trail.

John P. Coburn was born between 1809 and 1813 (one estimate says 1811) in Boston. A free African-American man, Coburn worked in the 1820s as a house-wright, and later ran a clothing business on Brattle Street. Before 1835, Coburn lived at the western corner of Southac Street (now Phillips Street), but on February 17, 1835 he purchased a home at 3 Coburn Court. In 1843, Coburn commissioned architect Asher Benjamin to design his new home on 2 Phillips Street, where Coburn and his family moved the following year. Coburn married Eveline Gray, from New Hampshire, and they adopted a son named Wendell. His brother-in-law, Ira Smith Gray, a caterer, married Louisa Nell, the sister of abolitionist William Cooper Nell in the early 1840s. Ira S. Gray lived with John P. Coburn at 3 Coburn Court prior to the Coburn family’s move to 2 Phillips Street.

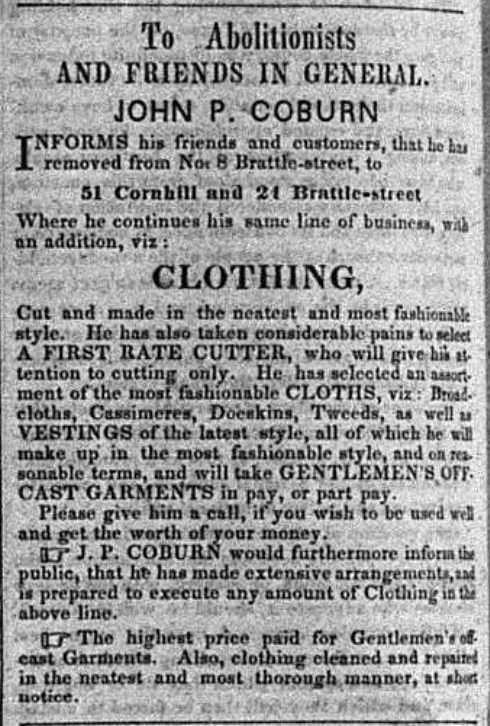

Coburn’s clothing business stood on Brattle Street, opposite to the City Tavern. He entered into business with Jonas Clarke and Cyrus Foster, two other well-known Black Bostonians of the era. Coburn had deep ties to Boston’s abolitionist movement both as a Black business owner who raised money for abolitionist organizations and as a direct actor in the movement. He advertised his clothing business in William Lloyd Garrison’s abolitionist newspaper The Liberator. In the January 31, 1845 issue, the advertisement announced “to abolitionists and friends in general” that Coburn moved his store, which sold clothing “cut and made in the neatest and most fashionable style,” from 8 Brattle Street to 51 Cornhill and 21 Brattle Street. Not only did Coburn call himself “a first rate cutter” (“cutting” refers to the sizing and shaping of tailored clothes), he also paid the highest prices in Boston in exchange for “gentlemen’s off-cast garments” to consign at his store.

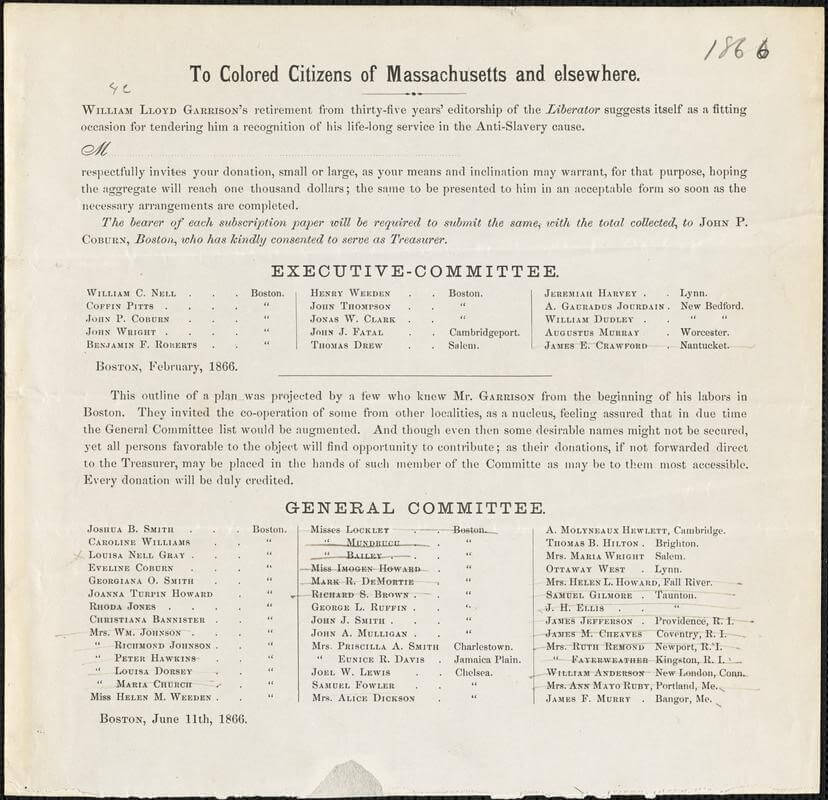

When Garrison retired in February 1866, after thirty-five years of editing The Liberator, John and Eveline Coburn joined William Cooper Nell, Louisa Nell Gray, Benjamin Roberts, George Ruffin, and other abolitionists to raise money for a gift of $1,000 to Garrison in “recognition of his life-long service in the Anti-Slavery cause.” Nell’s announcement of the planned gift sought donations from “Colored Citizens of Massachusetts and elsewhere” in Garrison’s honor. Coburn was selected as treasurer, to collect and add up the donations, on account of his experience as treasurer for the New England Freedom Association (since 1845). The New England Freedom Association sought to assist escaped slaves who used the network of the Underground Railroad to seek freedom. Coburn also signed petitions for the desegregation of Boston’s schools, and joined the Boston Vigilance Committee, founded in 1841 to protect escaped slaves from being kidnapped. Coburn was tied to the rescue of Shadrach Minkins in 1851, a “fugitive slave” (following the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850) who was captured by slave catchers in Boston. When Minkins stood trial at a Boston courthouse, a group led by Lewis Hayden (a self-emancipated man and one of Boston’s great Black Abolitionists) broke into the courtroom and took Minkins with them; Minkins was successful in defying the Fugitive Slave Act and reaching Canada. Witnesses to the events alleged that Coburn was “making inflammatory remarks” in the hallway of the courthouse “shortly before the rescue began.” Coburn and Robert Morris, one of the first Black attorneys in the United States, were arrested on March 1, 1851 for “aiding and abetting” the rescue of Minkins; both were tried and acquitted. He and his fellow Brattle Street clothiers, Jonas Clark and Coffin Pitts, posted bail for James Scott, who was also arrested and acquitted for assisting Minkins. After the rescue of Minkins, Coburn joined other Black community leaders in founding a Black militia called the Massasoit Guards. The Massasoit Guards prepared for community self-defense in order “to discourage slave catchers” and “bolster the courage of the threatened community” after the Fugitive Slave Act forced state authorities to assist slave catchers, according to historians James and Lois Horton.

Later in life, Coburn created a “gaming house” out of his residence at 2 Phillips Street with Ira Gray. Both Coburn and Gray were very fond of gambling; the Boston Courier once described Gray as “the handsomest quadroon [one-fourth Black] of his day, and the most accomplished gambler ever seen in Boston.” Historian Walter Muir Whitehill received this undated Courier clipping from a colleague, and noted its mention that Gray “with his brother-in-law, Coburn, kept at the corner of Southac and North Russell Streets a ‘private place’ that was ‘the resort of the upper ten who acquired a taste for gambling.’” In 1976, researchers for the Museum of African American History discovered and documented the sites of Coburn’s home (as of 1831), and his gaming house (built in 1843-1844). Byron Rushing, former president of the Museum of African American History, added Coburn’s home as a Black Heritage Trail site because “to have a gambling house…is going to make the interpretation of these sites a little more realistic. No one is attempting to say when we describe this community that everything was wonderful and above board and everybody went to church.”

When Coburn died in 1873, he passed on his home to Wendell; Wendell’s wife survived him, and lived at 2 Phillips Street until the turn of the twentieth century. Coburn also left money aside for multiple Black organizations, including the Home for Aged Colored Women on Myrtle Street (incorporated in 1864). The money Coburn left aside very likely came from the wealth he generated from the gaming house, in addition to his successful clothing business.