The West End Mothers’ League

The West End Mothers’ League organized mass meetings and boycotts to address the high cost of food in 1917, just before the United States entered World War I.

In 1917, the West End Mothers’ League was a grassroots organization of women in the historic West End who protested high food prices and demanded city intervention to aid starving West Enders. Food prices increased substantially across the nation after the summer of 1916, not only because of widespread crop failures from disease and bad weather, but also due to increased purchases of American crops by Britain, France, and Italy as European agriculture declined during World War I. The consequences of high food prices hit the working-class families of the West End especially hard, and the West End Mothers’ League organized in response to this problem. The organization, chaired by Eva Hoffman who lived on 125 Leverett Street, included women who resided on Auburn, Revere, Cambridge, South Russell, and Staniford Streets. Members included League chair Eva Hoffman (125 Leverett Street), Ettie Epstein (13 Auburn Street), Dora Chkowsky (50 Revere Street), Mrs. Max Bloomberg and her daughter, Rose, (238 Cambridge Street), and many others.

Between February 19-23, 1917, food riots emerged in Boston, New York, and Philadelphia in response to growing food shortages and high prices. After one demonstration in Boston, a crowd of 800 people, mostly women and children, looted a West End grocery store and were suppressed by police. A special dispatch to the Cincinnati Enquirer reported on events in the West End during this period. The report described conditions in the neighborhood as follows:

West End stores have boosted prices on sugar and salt to previously unheard of figures, and there was incipient food riots in progress in certain parts of that section this afternoon and evening. Every part of the city is suffering from the abnormal conditions, and potatoes are being sold by the dozen in many places. In Boston proper they sell for 25 cents a dozen. Restaurants have stopped giving potatoes with orders and now charge 5 cents a portion for them.

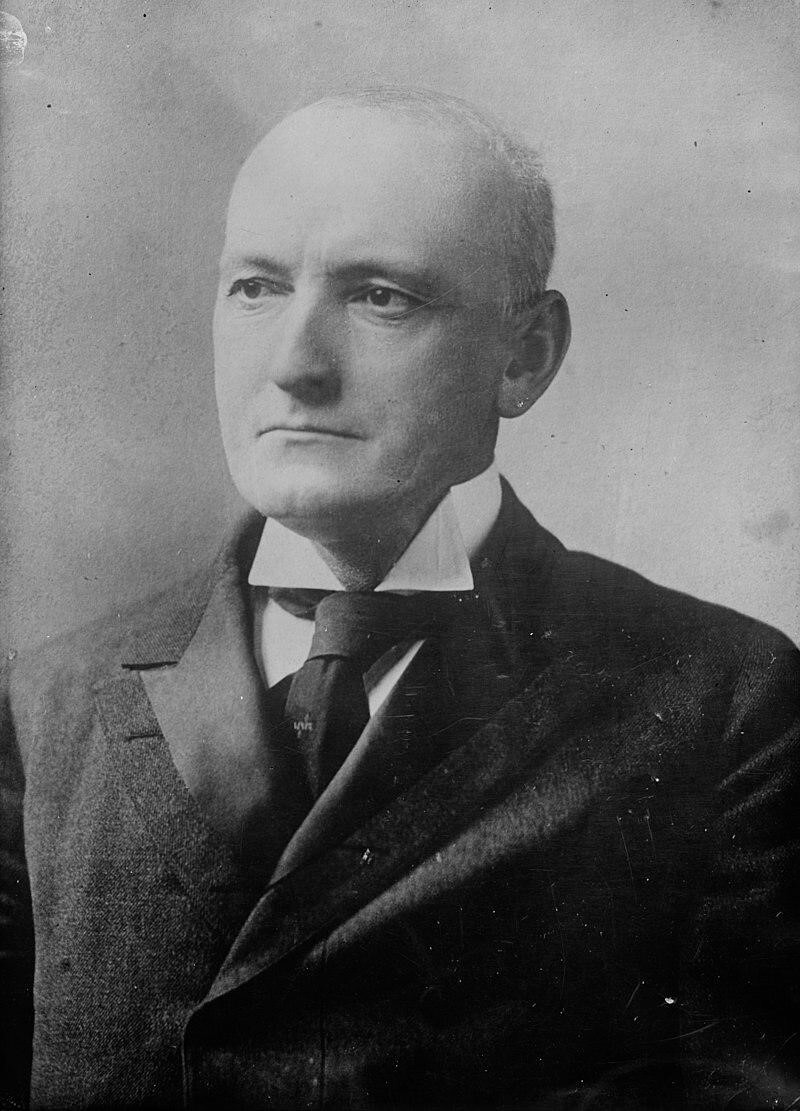

The morning of February 23, 1917, twelve women (and two of their daughters) organizing with the West End Mothers’ League arrived at Old City Hall, on 45 School Street, to request the use of Faneuil Hall the following night for a mass meeting. The mothers and daughters of the West End were joined by a large crowd representing additional women-led civic associations and sympathetic residents. The head of the West End Mothers’ League delegation, Eva Hoffman, asked James Storrow, president of the City Council and acting mayor in James Curley’s absence, if the Mothers’ League could use Faneuil Hall without paying the $15 fee which they could not afford. Storrow said that he did not want to make this decision when Mayor Curley was returning to Boston from Chicago, but that Fred Kneeland, Superintendent of Public Buildings, could telegraph the mayor on his train. Kneeland, who supported the West End mothers’ resistance to high prices for basic necessities, insisted that if Curley would not waive the fee to use Faneuil Hall for the meeting, he would pay the fee out of his own pocket.

The West End Mothers’ League promoted their meeting scheduled for February 24, 1917 by holding open-air gatherings to inform residents of when and where it would take place. The Transcript-Telegram, a local paper in Holyoke, MA, reported on February 24 that “despite the rainy and otherwise disagreeable weather West End women gathered for several outdoor mass meetings and showed their indignation in many ways.” The Mothers’ League’s cause gained more traction as G.W. Anderson, U.S. District Attorney for Massachusetts, called a grand jury for Tuesday, February 27, 1917, to hear witness testimony about “a number of West End merchants who are declared to have charged exorbitant prices.” The grand jury would be presented with unpublished findings, from a special state Commission on the Cost of Living, that “violations are being made in regard to the food prices by meat packers.” In the early twentieth century, the Federal Trade Commission investigated packers for price fixing through “short weights and excessive charges for feed and yardage.” The West End Mothers’ League drafted resolutions which addressed other root causes besides price fixing, advocating for “a national embargo on food shipments to Europe and control of food distribution for the public good instead of speculative profit.” Governor Samuel McCall, on February 20, 1917, echoed the West End Mothers’ League’s demands when he advocated for government action on food prices. McCall, in an address, declared that “this country, like those abroad, must do something to regulate prices. We are in a state of war as far as the cost of living is concerned…”

In March, although food prices began declining, they remained prohibitively expensive for West Enders. The West End Mothers’ League continued organizing for a school boycott and a consumers’ boycott. The night of March 1, 1917, the West End Mothers’ League joined organizations including the Labor League and United Hebrew Trades of Boston to demand that Mayor Curley arrange for free breakfasts in Boston schools, lest parents keep their children at home. The delegates who came together at a mass meeting, in the Shapiro Building on 38 Causeway Street, represented 3,000 school-age children and organizations with a combined 27,000 members. Mayor Curley indicated that state law did not allow Boston schools to provide free breakfasts, though he forwarded the proposal to Joseph Lee, chair of the School Committee. Lee had quickly shut down the proposal, asserting that the School Committee could not take on the responsibility for providing free breakfasts. Curley had just arranged with the W. & A. Bacon Company for them to sell “6,000 bushels of potatoes at 65 cents per peck” to Boston residents. Because state law also prohibited the Mayor from officially selling food, he put up $16,000 as a private citizen for the Bacon Company to sell potatoes, rice, and sugar to constituents.

The West End Mothers’ League’s consumer boycotts were successful, such that when consumers organized a boycott of chicken on March 7, 1917, “not a single bird was sold in the entire West End.” Members of the West End Mothers’ League and South End Mothers’ Club also picketed slaughterhouses in Boston. Eva Hoffman worked to organize mothers in every suburb of Greater Boston in order to collectively wield their purchasing power against, in the words of the Boston Post, “organized selling of foodstuffs and corporate regulation of prices for necessities on a continuous rising scale.” Hoffman announced on March 14 that 200 women in Lawrence formed their own Lawrence Mothers’ League that would participate in larger boycotts. Rabbis met at the Wall Street Shul in the West End to discuss whether to have cutters in “local Jewish chicken slaughter houses” withdraw their labor in order to “compel stoppage of chicken sales” and reduce prices.

After the United States entered World War I on April 6, 1917, Congress enacted, in August that year, legislation to enable a wartime Food Administration to control production and distribution of foodstuffs “for the national security and defense.” The Food Administration is credited by statisticians Raymond Pearl and Magdalen Burger with having been “effective in limiting the exaction of excessive prices by the local retailer,” through licenses that regulated the conduct of wholesalers that grossed over $100,000 a year. Grassroots activity in the West End against high food prices in this era, responded to a pressing problem, which federal intervention ultimately helped address once the nation was in a state of war.

Note: Additional members of the West End Mothers’ League included Ettie Epstein (13 Auburn St.), Dora Chkowsky (50 Revere St.), Mrs. Max Bloomberg and her daughter, Rose Bloomberg (238 Cambridge St.), Elizabeth Downs (58 Allen St.), Mary Bourdon (13 South Russell St.), Clara Bacowsky (30 Staniford St.), Fannie Rockmolivitz (34 South Russell St.), Dora Bornstein (17 Auburn St.), Gertie Ainbender (18 Auburn St.), Mrs. Francis Yockielman (20 Auburn St.), and Mrs. Fritz and Eva Fritz (66 Barton St.).

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Raymond Pearl and Magdalen Burger, “Retail Prices of Food During 1917 and 1918” (2012), Alan Singer and Jasmine Torres, “1917 Food Riots Led by Immigrant Women Swept U.S. Cities” (2018), Tom G. Hall, “Wilson and the Food Crisis: Agricultural Price Control During World War I,” Agricultural History 47:1, January 1973, Charles Wood, “Monopoly and Confusion: Stockyards and Packers, 1900-1920,” The Kansas Beef Industry (2020, JSTOR); Boston Globe (“Food Protest by West End Women,” February 23, 1917, page 1; “Women Protest High Food Cost,” March 8, 1917, page 13; New York Times (“Boston Women to Protest,” February 24, 1917, page 3); Transcript-Telegram (“Special Grand Jury,” February 24, 1917, page 1); Boston Post (“Organize Mothers in Big League,” March 1, 1917, page 1; “School Children Must Have Food,” March 2, 1917, page 9; “Lawrence Housewives Organized,” March 15, 1917, page 20)