Leo Stone’s “Pin Money Club” and the Pyramid Club Craze

Leo H. Stone of the West End founded the “Pin Money Club” after the similarly designed “Pyramid clubs” grew rapidly throughout New England in 1949. Whereas pyramid clubs were “get rich quick” schemes vulnerable to racketeering, Stone’s Pin Money Club was based on smaller payouts and legally legitimate practices.

On April 2, 1949, the New York Times reported that the “Pyramid Club craze” reached New England “with the force of a cyclone.” Pyramid clubs were lotteries based on entrants paying a starting fee, usually $1 or $5, in hopes that they get selected to receive a large payout. Everyone that paid into a pyramid game was expected to find two more people to pay; those two would find four more people, those four would find eight, and the pot multiplied. Any player who recruited more people to join the pyramid saw their “position” on a list of players improve, and the winner of the pot – once the “chain” of contributions is broken after a number of days or weeks – is whomever happens to have their name at the top of the list. Pyramid clubs were a get-rich-quick fad that quickly became popular in Boston and other cities, yet just as quickly came under the scrutiny of the law. Massachusetts did not operate a state lottery until September 1971; before then, residents participated in informal schemes like pyramid clubs that were vulnerable to racketeering. The quick rise and fall of pyramid clubs inspired Leo H. Stone, a West Ender who lived at 6 Goodwin Place, to create his own “Pin Money Club” as a legal and legitimate alternative to pyramid clubs.

Some people received substantial payouts through pyramid clubs; one notable winner was Mrs. William R. Edmonds from Arlington. The Globe reported in March 1949 that she won $2048 in a pyramid club two weeks after paying just $8. But others became victims of racketeering. In April 1949, an unnamed woman from Brookline announced that she would seek a state investigation into a pyramid club operator in Brookline who, she alleged, moved his friends’ names to the top of the lists. The Brookline resident was suspicious when, during a house party of pyramid club players, one name that was fifth on the list was crossed out with no explanation. The party host received a phone call requesting to put another name in fifth; after party-goers inferred that the previous name was fictitious, they all left the party in frustration. This incident in Brookline was brought to the attention of Edmund Dewing, District Attorney for Norfolk County, and he encouraged anyone with complaints about pyramid clubs to submit them at an upcoming grand jury meeting. The first criminal prosecution of a pyramid club in New England took place on April 20, when club operators in Dedham paid out just $18,000 after announcing a “possible total payoff of $75,000 and $100,000.” The pyramid operators who swindled their players were known as “clip artists.”

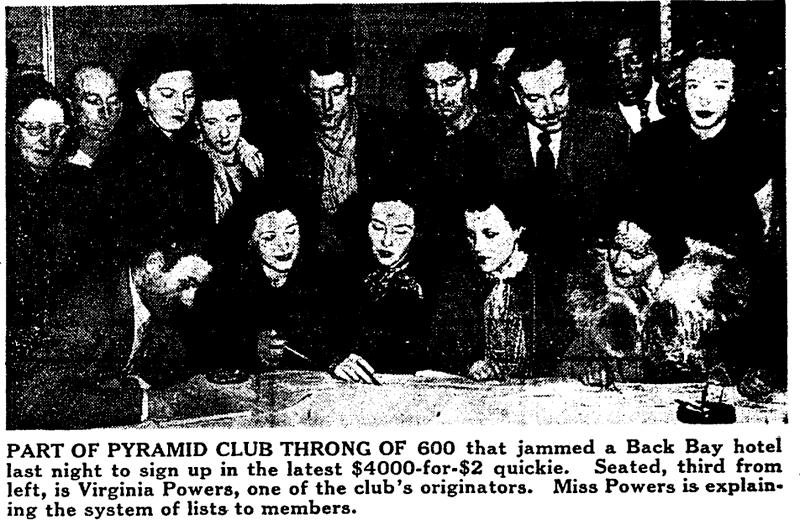

In April 1949, an apparently more legitimate version of the pyramid club emerged at a Back Bay hotel where Virginia Powers of Charlestown brought ten pyramid clubs together to streamline the game. Each entrant paid $2 to join the game without needing to recruit two more participants. The payoff was “$4000-for-$2,” and winners would be announced nightly. Each winner would pay $2 again to return their name back to the bottom of the list, and everyone else’s position moved up each time. Even the State House briefly ran a pyramid that raised $50 for the Children’s Medical Center Fund. According to the Globe, State Senate President Chester A. Dolan, Jr. and House Speaker “Tip” O’Neill, “who admitted being roped into the latest craze–urged recipients or prospective recipients of Pyramid Club funds to turn them over to a worthy cause.”

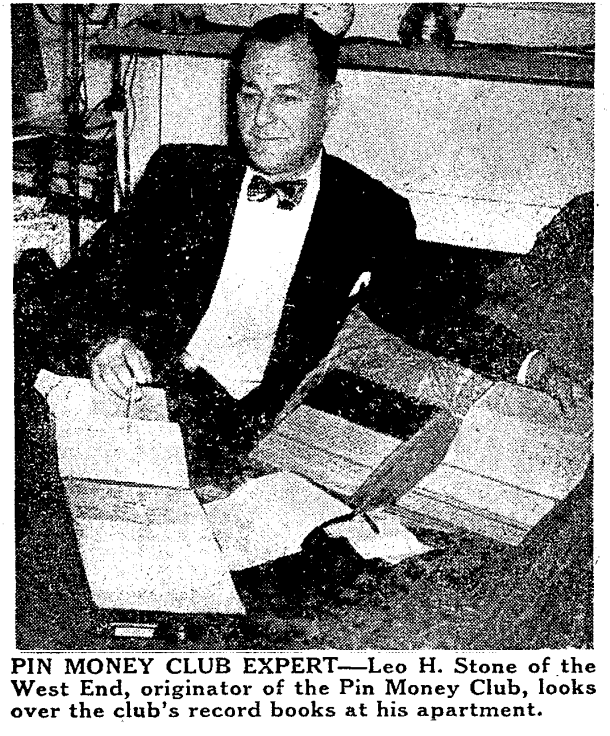

Leo Stone of the West End founded his “Pin Money Club,” which the Globe profiled in October 1949. “Pin money” is an older phrase for a small amount of spending money on nonessentials, though it once meant an allowance that a wife received from a husband. Stone was a baggage agent at a bus terminal in Boston and created the Pin Money Club as a “small profit plan” to pay back the people who had been “clipped” by fraudulent pyramid clubs. The Pin Money Club had a $2 entry fee, and the premise was “two will get you four–or six.” Winners were determined by a “simple system of rotation,” unlike the pyramid clubs where recruiting other players would improve your chances. Every six weeks, the two hundred members of the Pin Money Club would hold a payoff meeting. Stone insisted that “The way this works has nothing to do with the way the Pyramid Club operated,” especially because he hoped that the membership rolls would not grow out of control. Because most of the Pin Money Club’s members were from Arlington, Stone registered the club at the Arlington Town Hall, which he claimed as evidence for the organization’s legality.

The Pin Money Club is the best example of how West Enders experienced, and responded to, the “pyramid club craze” that swept Boston, and other towns and cities, in the 1940s. Newspapers like the Boston Globe often made tongue-in-cheek observations about the pyramid clubs, especially when they faded away. On March 27, 1950, the Globe declared, “It is now possible to date the Pyramid Club historically by saying that it all happened exactly one year before we came to our census” (pun intended).

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Source: New York Times (“New England: Pyramid Clubs Arrive Late, but Their Force Is Undiminished,” April 3, 1949), ProQuest/Boston Globe (“Editorial Points,” March 27, 1950; “Pin Money Club Is Strictly a Small-Profit Proposition,” October 13, 1949; “8 to Face Court on Pyramid Club Lottery Charges,” April 21, 1949; “New $4000-for-$2 ‘Quickie’ Latest Thing in Pyramids,” April 2, 1949; “Racketeers Invade Pyramid Clubs Here,” April 1, 1949; “Fresh Money, New Hopefuls Rush Into Pyramid Clubs,” March 30, 1949)