Bashka 'Bessie' Paeff

Though her humble immigrant background set her apart from her more affluent contemporaries, West Ender Bashka Paeff became a highly regarded member of the national arts establishment.

Sculptor Bashka Paeff, at times called “Bessie”, was born in Minsk, Belarus in 1893. Her family fled the Russian Empire when she was one year old, escaping the violent pogroms that targeted Jews across Russian-occupied Eastern Europe. The Paeff’s first settled in the North End; but quickly resettled at 6 Pinckney St. in the West End, where Bashka would eventually set up her artist’s studio, and where her parents would live for the remainder of their lives. Bashka attended the Massachusetts Normal School (today’s Massachusetts College of Art) where she studied with fellow sculptor Cyrus Dallin, and in 1914 she won a scholarship to study at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts.

While the majority of female artists of the day were wealthy, Bashka needed to work her way through school to help her parents and five siblings. As a ticket seller in the Park Street “T” station, she became known as the “subway sculptress” because she often worked in clay during lulls in her shift. She went on to win several competitions early in her career while earning a living making garden statuary and portrait busts of children. By the age of 23, Bashka became an important member of the Boston arts community, and won commissions to create busts of prominent figures such as Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and pioneering sociologist Jane Addams.

Reviews of her work tended to comment on her Jewish, immigrant, working-class status as much as the pieces themselves. Though being regarded as a novel immigrant success story could at times overshadow her work as a serious artist, she was embraced by prominent members of the city’s arts community. In 1916 she became a member of the Guild of Boston Artists, an organization with the mission of promoting Boston artists such as Bashka. The Guild’s founding membership was forty percent women; an impressive fact at a time when the art world was dominated by men. With the help of the Guild, Bashka often had showings in her home studio, eliciting the pride of neighbors.

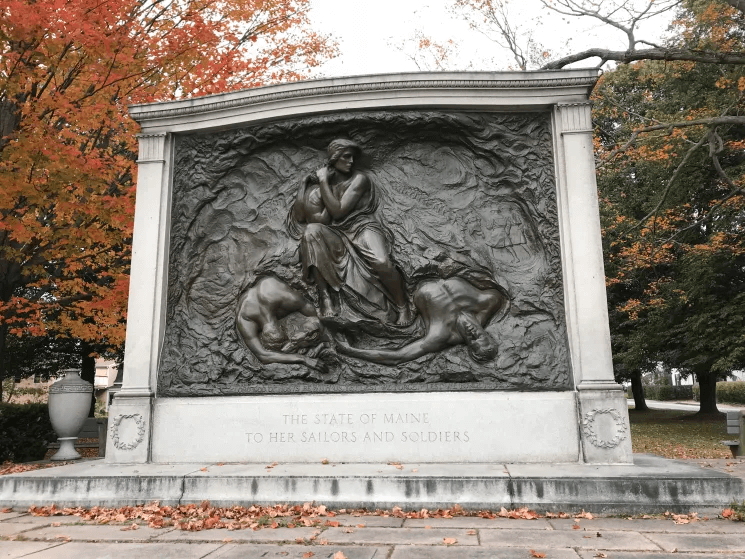

While Bashka was still a young artist, Governor Percival Baker of Maine awarded her the commission for his state’s Sailors and Soldiers Memorial (officially named Sacrifices of War). Baker’s successor rejected her piece as “overly pacifist” and required her to make changes to it before it was installed in Kittery in 1926. The work was controversial because it invoked the suffering of maternal sacrifice at a time when images of women protecting their young from the violence of battle were rarely seen in American art. Bashka intended for the sculpture to be a statement against war and said, “I have some decided opinions about war memorials. I hope most of all that we shall not erect memorials to glorify war. We forget what suffering and horror it brought.” Her stance was potentially risky. Overt displays of pacifist sentiment were often viewed as un-American, but she remained bravely vocal about her belief that women held a special responsibility as advocates of peace.

Bashka’s other well-known works include: the Boy and Bird Fountain installed at the Arlington Street entrance of the Boston Public Garden; the Lexington Minute Man Marker relief near Buckman Tavern in Lexington, MA, and Laddie, a statue of Warren G. Harding’s pet dog, which is housed at the National Museum of American History. When she was 47, Bashka married Boston University professor Samuel Waxman. They lived in Cambridge where she continued to sculpt and work as a Red Cross volunteer arts instructor for World War II veterans. One of her last pieces was a 1970 relief portrait of Martin Luther King, Jr. In 1979 she died in her home on Foster St. in Cambridge at the age of 85.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Hirshler, Erica E., Janet L. Comey, and Ellen E. Roberts. A Studio of Her Own: Women Artists in Boston, 1870-1940. Boston: MFA Publications, 2001; Boston Globe, Page 18, June 3,1914; Boston Globe, Page 6, June 28,1915; Boston Globe, Page 8, August 24,1925; Boston Globe, Page 12, March 3,1928; Boston Globe, Page 15, June 30, 1932; Boston Globe, Page 9, November 15, 1932; Boston Globe, Page 43, January 25, 1979; Wingate, Jennifer. “Motherhood, memorials, and anti-militarism: Bashka Paeff’s Sacrifices of War.” Woman’s Art Journal, vol. 29, no. 2, fall-winter 2008, pp. 31+.