Bernard Berenson

Bernard Berenson (1865-1959) was a Lithuanian-born, West-End-raised art historian and commercial art dealer specializing in the Italian Renaissance. His knowledge and expert connoisseurship greatly impacted the art world of the 19th and 20th centuries, and his dealings with wealthy Americans bolstered the flow of Old Masters into the country. His publications on Italian Renaissance artists were hugely successful and are still used in classrooms today.

Bernhard Valvrojenski was born in Butrimonys, Vilnius Governorate, Russian Empire (now Lithuania) in 1865. When Bernhard was ten years old, his family immigrated to America, settling in the West End of Boston. Here, they changed their last name to “Berenson”; Bernhard would keep the original spelling of his name until 1914, when he changed it to Bernard. The Berensons lived first at 32 Nashua Street, before moving around the corner to 11 Minot Street. At the time, the West End was home to around 100 Jewish people. Despite this, the Berensons had a hard time fitting in with the rest of the Jewish community. The older Jewish immigrants, mainly German, were wary of the newcomers. Moreover, the family did not attend synagogue because Bernhard’s father, Albert, subscribed to Haskalah, a type of liberal Judaism.

The Berensons were a close-knit family, and Bernhard was the only boy. His younger sister, Senda Berenson, would later become known as the “Mother of Women’s Basketball.” He was relatively close to his father, Albert, but their many similarities affected the young boy. Both men were intellectual and charismatic, able to hold the attention of an audience for hours. Yet, Albert was unable to pursue his intellectual interests due to the family’s need for money. Because of his lack of business talent, Albert set to work as a peddler. The young Bernhard witnessed his father’s resentments and promised himself he wouldn’t become the same frustrated intellectual, unable to meet his full potential.

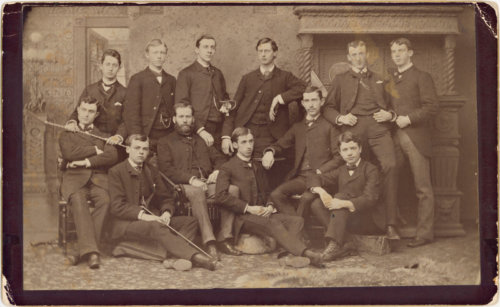

Berenson was a gifted young student. As a child, he astonished librarians with the sheer amount of books he read, visiting the public library several times a week. He matriculated to Boston University as a college freshman and transferred to Harvard a year later. He was a successful scholar there, becoming editor-in-chief of Harvard Monthly his senior year. But he was also conflicted: he was pursuing a degree in religion, writing a thesis on Talmudo-Rabbinical Eschatology, but was falling in love with the history of art, and hoped to obtain a traveling fellowship to further his studies.

Berenson’s charisma attracted wealthy Bostonians, who took him in as a protegé. Although Berenson did not receive the traveling fellowship, his art-loving associates provided him the substantial fund of $700 to go on a Grand Tour of Europe. During his trip, Berenson became infatuated with European art. He traveled everywhere to see the great masterpieces and remained long after the sponsored year.

While in Italy, Berenson noticed that Italian Renaissance art desperately needed sorting and authenticating, and he recognized the rising demand for art expertise now that America was emerging onto the art scene. He decided then and there that he would become a connoisseur of Italian art, master the field of attribution and authentication, and become an essential intellectual in the Renaissance field.

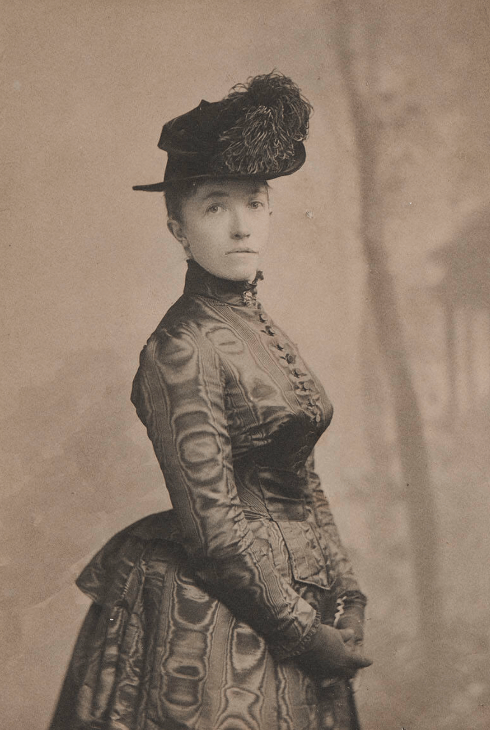

One of the Bostonians who funded his trip was Isabella Stewart Gardner, an eccentric heiress who had a knack for collecting. The two had met through a Harvard professor in 1886 and were instantly drawn to each other. Both were outsiders: him a Jewish immigrant at Harvard and her a transplant from New York. Over time, the two formed an intense friendship that developed into a business relationship. Their relationship mainly existed through their consistent overseas correspondence, which consisted of lengthy and somewhat seductive letters. Berenson’s skill for writing allowed him to combine business matters with emotional ones, all with the aim of capturing Isabella’s attention. In a letter to Isabella (January 19, 1896) in which he proposes an expensive painting by Giovanni Bellini, Berenson writes about the Fiesole hillside where he resides: “I would, dear Friend, I could despatch of this golden weather that I am basking in copious whiffs to you… The mildness of the changeless spring, the sweet odours of the Happy Island, the radiance of summer land is here this winter. I spend all the afternoons wandering about, ‘an embodied joy’ surely sharing more than my mere share of mortal happiness.” She responded (February 2, 1896): “The [letter] by the way made me quite frantic to fly to Fiesole and drink in the air – and perhaps saunter with you in the sunny afternoons. About the Bellini: the money bothers me. Perhaps I may be able.”

Around the time they met, Gardner had inherited her father’s fortune, and redirected her collecting effort from odd trinkets to prestigious works of art. Berenson’s first dealing with Gardner was the acquisition of a painting by Renaissance painter Sandro Botticelli, The Death of Lucretia (c. 1500). In December 1894, four months after Berenson had first written to Isabella about the Botticelli, the pair met in Paris and went to the Louvre together. The next day, Isabella agreed to buy the painting from him for 3,000 pounds. This exchange paved the way for a new direction in American art collecting, as it was the first Botticelli to travel to America. From here, Gardner and Berenson entered into a partnership, the former enlisting him as a scout for Old Masters. Berenson was promised 5 percent commission on each sale.

Berenson’s investigative efforts for Gardner resulted in the foundational masterpieces of the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. Both wanted the museum to be a resource and guide for the city. Berenson never forgot his experience as a child yearning for a culture to which he had little access. The Museum would provide an experience usually available only to the very wealthy: the chance to experience great art and enjoy it for the sake of beauty. Between 1894 and 1903, Berenson would help Gardner spend more than a million dollars on upward of 40 paintings.

One of the prize pieces of the Museum is The Rape of Europa (1559-62) by Titian. Berenson informed Gardner about its existence, as he thought she would be attracted to its flamboyant and erotic nature. He told her the cost was 20,000 pounds, which she ended up meeting, along with his 5 percent commission. However, this transaction wasn’t completely transparent. In fact, Berenson did not tell Gardner that the 20,000 pounds wasn’t the official price at all; the price would actually be determined by what she was willing to pay. The owner’s dealer, Otto Gutekunst, ended up acquiring the piece for 14,000 pounds, 6,000 pounds less than what Gardner had already paid. Berenson never revealed the true nature of this transaction. He sent Gutekunst the 14,000 pounds for the owner and 2,000 pounds for Gutekunst himself. Berenson kept the remaining 4,000, and Gardner’s commission. Despite the hefty price she paid for it, Gardner was ecstatic. She wrote to Berenson afterward to expound her love for the painting and her gratitude to him.

The shady Europa deal was not Berenson’s only ethically-dubious moment. In fact, Gutekunst, who helped Berenson with the Europa deal, helped him with the Botticelli as well, along with the majority of Gardner’s acquisitions. This wouldn’t have been unusual, except for the fact that Berenson claimed to Gardner he was dealing with the owners personally, when he was actually dealing through Gutekunst’s firm in London. In turn, Berenson was able to get his hands on great pieces, and got all of the credit. He would often draw commissions from both sides of the deal and inflate prices. Gutekunst urged Berenson to tell the truth as the Gardners became increasingly suspicious, and Berenson was almost revealed a few times. He never told the truth, however.

With the help of his mistress-turned-wife Mary Costelloe, Berenson wrote a series of groundbreaking publications on Italian Renaissance art throughout his career. His first publication, Venetian Painters of the Renaissance (1894), established Berenson as an expert on Italian art. In this book, he published his curated list of the 34 Renaissance painters that make up the Venetian School, and the paintings attributed to them. This list was revolutionary and quite contrary to past claims: for example, Titian, once said to have 1,000 surviving paintings, was attributed 133.

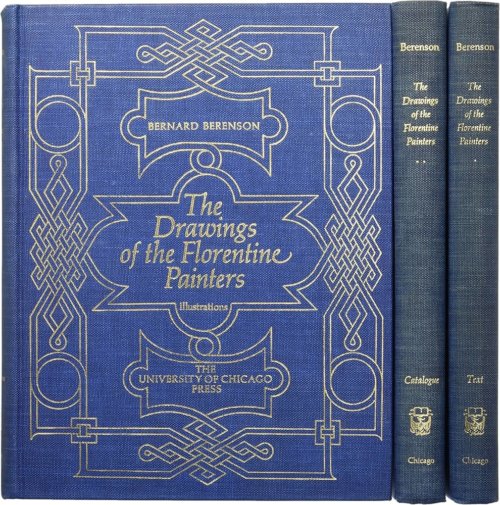

Berenson’s Drawings of the Florentine Painters (1903) is still used among art historians and museum curators today. This publication consists of two massive volumes: the first contains an organized selection of Berenson’s thoughts on a few Tuscan painters and their works, and the second contains the drawings of the Florentine school, each accompanied by Berenson’s attribution. No such attempt at an overarching catalog of Old Master drawings had been attempted before this.

While working on Drawings, Berenson registered that he would have to find clients other than Isabella Gardner. This realization, coupled with his tumultuous marriage to Mary and their move to Italy, began a new, rocky stage of his life in which he became extremely self-critical. Although Drawings established Berenson as a master in his field, the man himself thought he had sold himself out to the commercial art world. He believed he had veered away from his intellectual pursuits for the sake of livelihood.

In the second part of his career, Berenson expanded on his previous lists and became more involved in the art market. At the same time, his contemporaries began to peck away at his reputation. In the aftermath of Drawings, the art critic Roger Fry asked Berenson to be involved in a new magazine called the Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, which still exists today. Soon enough, however, the magazine slighted Berenson when they had a different connoisseur, Langton Douglas, write about the Sienese painter Sassetta, despite Berenson’s possession of his work. Moreover, the magazine allowed Douglas to add sneering annotations to Berenson’s later article about the painter. Consequently, Berenson insulted Fry, left the magazine, and introduced an array of enemies into his life who would seek errors in his work for years to come. The subsequent criticisms and accusations would haunt him long after his death.

Berenson’s second long-term business partner was Joseph Duveen, a burgeoning art collector who had purchased Randolphe Kann’s 4 million dollar collection to kick off his career. In 1907, Berenson agreed to authenticate the collection, which led to a contract that would define 25 years of Berenson’s life. The contract stated that Berenson would be paid 25 percent of the profit on any painting that Duveen acquired per his advice. In exchange, Berenson would represent Duveen in the Italian market and remain available for authentication. Both parties wanted the partnership to remain secret, as Berenson didn’t want to be known as a mere worker on Duveen’s payroll, while Duveen wanted clients to think he certified his paintings independently. In total, Berenson made around $150,000 from the Duveen partnership.

In the meantime, World War I was raging on. Berenson personally witnessed the destruction at the fronts and handily criticized the Treaty of Versailles for being too hard on the Germans. In turn, he became strongly anti-Fascist and impatient with American politics. Nicky Mariano, the new librarian at his villa and library I Tatti, shared similar sentiments, and the two bonded. A romance eventually grew that would last until the end of Berenson’s life. While losing face in Italy due to his anti-Fascism, Berenson was also losing authority in America. A lawsuit against Duveen revealed that Berenson was on Duveen’s payroll; as a result, Berenson broke off relations with Duveen in 1937.

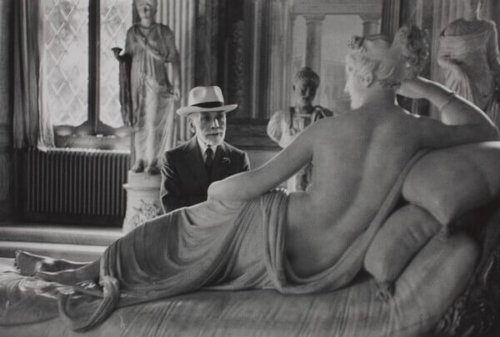

During World War II, Berenson worked hard to usher Jewish friends to safety in England or America, although he himself did not want to leave Italy. When the Germans took over Italy, Berenson and Nicky went into hiding at a friend’s villa for almost a year. Meanwhile, an operation was underway to hide and preserve the content of Berenson’s library at I Tatti. Precious paintings were hidden while lesser works were placed on the walls. I Tatti was one of Berenson’s greatest accomplishments. Throughout their lives, Berenson and Mary would host an array of personalities at the villa, and Berenson’s collection was housed here. He desired to bequeath his library to Harvard after his death.

During the war and for the 14 years afterward, Berenson was highly productive. He wrote essays such as Aesthetics and History in the Visual Arts and The Arch of Constantine or the Decline of Form, along with five books of personal reflections. All the while, he continued to host his peers and loved ones at his villa. On October 6, 1959, Berenson passed away, and was buried in the chapel at I Tatti. For nine years afterward, Nicky tended to his legacy: she finalized the bequest to Harvard, published two of Berenson’s posthumous books, and wrote her memoir Forty Years with Berenson.

Article by Parker Blum, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Rachel Cohen, Bernard Berenson: A Life in the Picture Trade (Yale University Press, 2013); Cynthia Saltzman, Old masters, new world: America’s raid on Europe’s great pictures 1880-World War I (Viking, 2008); Cynthia Saltzman, “Botticelli Comes Ashore”;Ernest Samuels, Bernard Berenson: The Making of a Connoisseur (Harvard University Press, 1979); Ernest Samuels, Bernard Berenson: The Making of a Legend (Harvard University Press, 1987).