Boarding Houses in the West End

Boarding Houses played an important role in the housing system during the age of industrialization and immigration in Boston and the West End. Along with lodging and rooming houses, they were the only alternative for those in need of affordable and transitional living space in the neighborhood until the arrival of tenements and apartment buildings. Boarding houses also offered women of the period one of the few ways to earn a decent income.

During the course of the 19th century, it is estimated that 30-50 percent of urban residents lived in boarding houses or took in boarders. Boarding houses were an essential part of growing cities and had a profound impact on American culture. In Boston there were 583 boarding houses in 1860, mostly concentrated in the West and South Ends. A majority of the population was as likely to live in boarding houses as in private homes. As one 1874 Boston Globe article stated, “the West End, once the stronghold of the ‘blue-blooded’ aristocracy of the Hub, has come, in these latter days, to be the very centre of boarding-house life. Within its limits are to be found all classes of houses and all ‘styles’ of boarding.”

In the 1870s, the encroachment of industry led to a fall in housing market values. Many middle-class Bostonians abandoned the city center for the new commuter suburbs, while others moved to the Back Bay. The new owners of the stately homes left behind often transformed them into boarding houses to profit from the influx of immigrants and migrants from rural areas seeking work. Other boarding houses, especially those occupied by single widows, might be family homes altered for the income opportunity.

Types of boarding houses varied and catered to a diverse population; from houses for sailors along the waterfront, known for their rowdiness, to those welcoming immigrants of specific nationalities, and upscale, fashionable homes such as the selective and genteel Harrison Gray Otis House, on Cambridge Street, and others on Beacon Hill. The terms are sometimes used interchangeably, but there were significant differences between boarding, lodging, and rooming houses. Boarding houses provided residents three meals per day (served at a common table), housekeeping and sometimes laundry service. They were also a source of companionship, protection, and even entertainment. Lodging and rooming houses provided neither meals nor housekeeping.

It was common for women of the age to run boarding houses, given the limited employment opportunities afforded to them. While many of them were widows, single and married women also took in boarders and managed the domestic, financial, and social responsibilities of the home. When married couples ran a boarding house, the husband tended to be relatively absent. He typically did not have meals with the boarders, that being left to the landlady, and he did not participate in the majority of the labor. With boarding, domestic labor became a service commodity that offered women another means to make a living. In the mid-19th to early 20th century, women could earn up to 70 percent of the earnings of a man working in a mill or mine, though that might have required the women to work around the clock, while still providing the unpaid labor of caring for their families.

Middle-class boarding houses made great efforts to maintain a reputation of respectability. Rather than calling their home a boarding house, an owner might advertise a room “with a private family,” downplaying the arrangement as a commercial endeavor for the landlady. While some owners of boarding houses advertised in newspapers, many rarely resorted to such marketing. This is especially true for boarding houses catering to immigrants. For example, owners of Irish boarding houses tried to attract their fellow countrymen by word of mouth. By the early 1900s, the West End had several Polish, Russian, and Italian boarding houses, often occupied by rent-paying family friends or relatives of the proprietors. Many of Boston’s hotels and most boarding houses during the immigrant era were racially segregated. An exception was Louisa Morrill, who ran boarding houses on Leverett St. and Crescent Place, where her boarders were, “a cosmopolitan mix of New Englanders, Canadians, Europeans, and a sole African American.” The West End and the north slope of Beacon Hill likely had the largest concentration of Black women-operated boarding houses in Boston, a city where 40% of Black households included borders.

Some urban reformers of the 1880s viewed boarding and lodging as culturally dangerous and pushed for more single family homes as a way to solve the problems of the city. The economic independence women gained as boarding house owners plus the moral atmosphere of strangers living together was seen as a threat to American life. Worse than boarding, lodging houses lacked the structure of family life that boarders enjoyed. In 1905, Albert Benedict Wolfe wrote The Lodging House Problem in Boston. Lumping boarding houses and rooming houses together, he viewed them both as a “grave and far reaching social problem.” Robert A. Woods proclaimed in Americans in Progress (1902), that “the first enemy of the home life of the West End was not…of foreign immigration, but of increase in native population drawn in by the growth of the city’s trade. Boardinghouses, and not tenements, here put the homes to flight.”

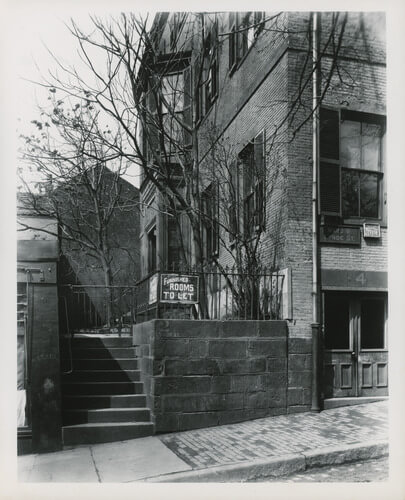

Boarding house life rapidly declined in the early 20th century, having been mostly replaced in cities like Boston with tenement houses, though there are references to boarding houses as late as the early 1950s in the West End. Sisters Mary and Helen Sherkanowski had fond memories of growing up in their mother’s boarding house in the West End. They opened their own boarding house in Charlestown and in 1952 wrote a book, Rooms to Let, about their experiences.

Article by Janelle Smart Fisher, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Boston Globe Sep 26, 1874 (To Let): Boston Globe Dec 02, 1874 (Boarding in Town…); Boston Globe May 25, 1952 ( Charlestown Landladies – Book Review); Boston Globe January 13, 2013 ( “Boardinghouses: where the city was born”); Gamber, Wendy. The Boardinghouse in Nineteenth-Century America. Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.; Historic New England https://otis.house/location/boarding-house-era-room/; Woods, Robert Archey. Americans in Process. Houghton. Mifflin and Company, 1903.