Bowdoin Square, Part 2: 20th & 21st Centuries

Bowdoin Square has gone through many phases, including rapid development, growing population, changing fortunes, urban renewal, and attempts at revitalization. Today the name survives mainly in the name of an MBTA station, but examination of Bowdoin Square provides insight into two and a half centuries of Boston history. This article, the second part of two, covers the history of the square in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

Note: To read “Bowdoin Square, Part 1: 18th & 19th Centuries” click HERE.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, fast-increasing immigration transformed large parts of the North End, West End, and the back slope of Beacon Hill into areas of high-density tenements, affecting the fortunes of Hanover and Cambridge Streets. In Bowdoin Square, an 1898 street atlas shows a hodgepodge at the turn of the century: boarding houses and apartment buildings; several small hotels; the handsome Bowdoin Square Baptist Tabernacle hanging on; and the new Bowdoin Square Theatre at the edge, halfway to Scollay Square.

The Bowdoin Square Theatre had opened on Cambridge Street in 1892, near the Scollay Square entertainment area. With a capacity of 1,500, it became one of the most popular theaters in Boston, hosting plays; vaudeville acts with gymnasts and singing comedians; and by 1912, motion pictures. A waitress named Billie Lee remembered the buzz in the theater during World War II: “The war was on; there was nothing but sailors… I worked there when the war ended––VJ Day… Oh, it was really something! It was beautiful!” Although the theater stood until Scollay Square and nearby blocks were demolished in the 1960s, its heyday ended after the war.

In the 1920s, Bowdoin Square underwent major changes, as seen in street atlases from 1922 and 1938 (above). The 1922 atlas depicts the square in flux, shown by the prominent white areas on the north and south edges of the square. It is not clear if the lots were completely empty in 1922, but in any case the properties were in transition. In 1925–1926, Cambridge Street was significantly widened to make more room for cars. By 1930, three new and large buildings nearly encircled the square: the Bowdoin Square Garage, the New England Telephone and Telegraph Building, and the Bowdoin Square Firehouse. The Telephone Building remains one of the most significant Art Deco buildings in Boston. Its distinctive limestone façade has twenty-one vertical piers. A plaque on the front proclaims it as the site of the birthplace of Charles Bulfinch.

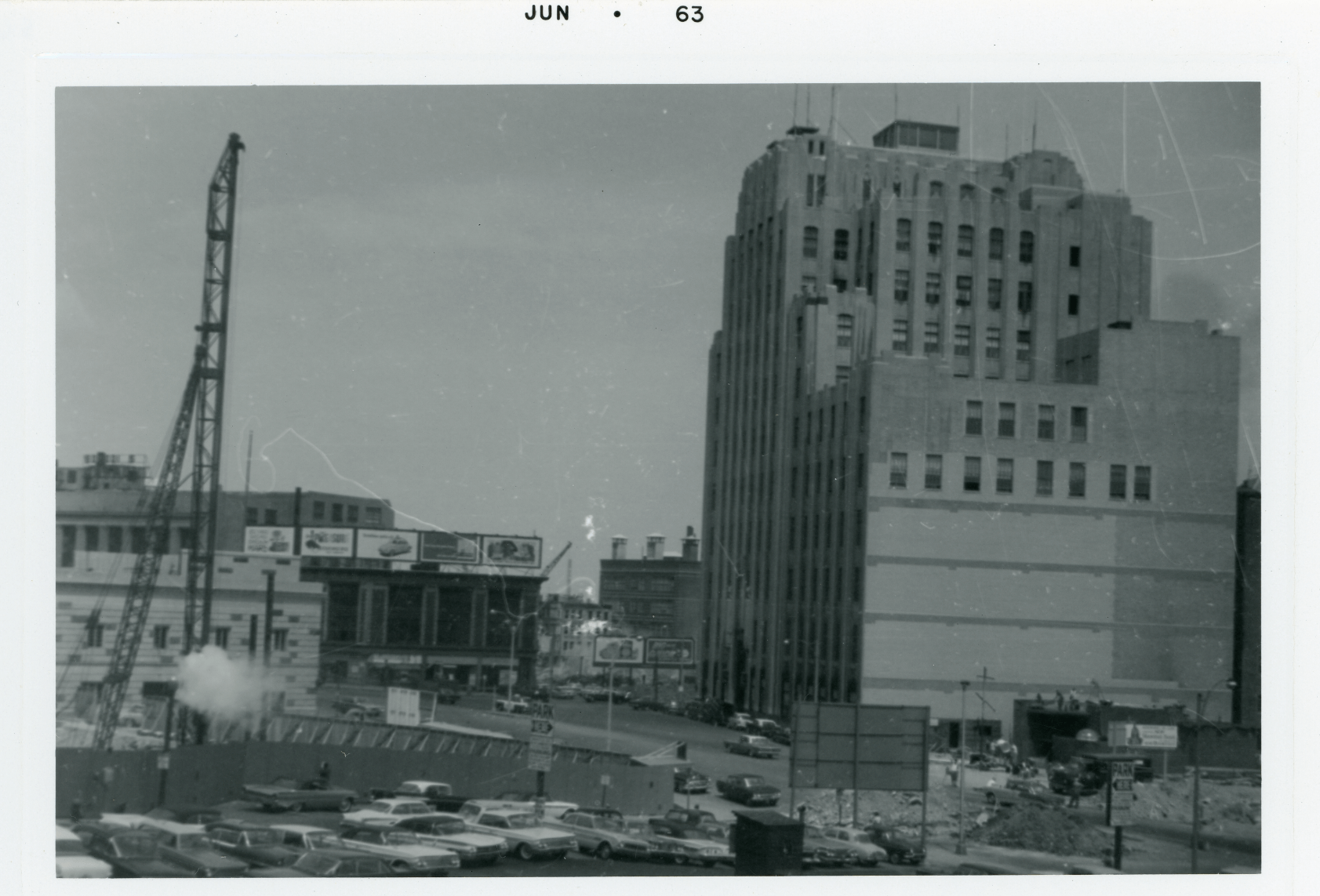

Across Cambridge Street, on the former site of the Revere House, another imposing building opened in 1930: the Bowdoin Square Firehouse, the largest fire station ever built in Boston. Called the “Big House” by firefighters, the two-story limestone building had room for 73 men, 8 pieces of apparatus, and 2 water towers. In its prime, the Engines and Ladders stationed at Bowdoin Square responded to all first alarms in the West End, North End, Beacon Hill, waterfront, downtown, and parts of the Back Bay. Although this modern firehouse was intended to stand for many decades, it was ensnared in urban renewal and torn down in 1963. In The West Ender newsletter in 1986, a former West End resident commented: “Do you remember the most modern Fire Station at Bowdoin Square that was destroyed for progress?”

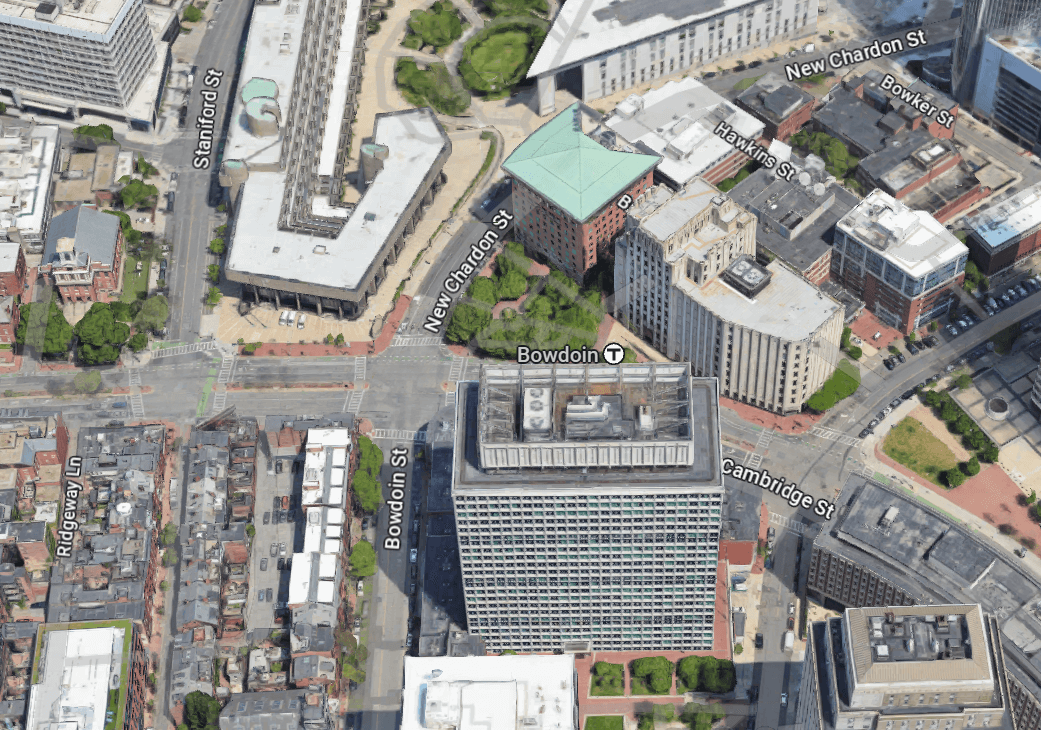

Bowdoin Square was on the edge of the West End destruction in 1958–1959, and then was directly hit by urban renewal during the 1960s. The area lost several streets, many buildings, and any remaining semblance of charm. Certain streets between the square and the State House, such as Bulfinch Place and Howard Street, disappeared. Nearly all buildings on Cambridge Street between Scollay Square and Bowdoin Square were torn down. The original Chardon Street was reshaped and turned into “New Chardon” Street to make room for government buildings. On three sides of the square, blocks lost their original grid structure and were turned into so-called superblocks of large, isolated buildings.

Around 1970, Bowdoin Square became dominated by two government office buildings: the Boston Government Service Center (BGSC) and the Leverett Saltonstall Building. The Government Service Center is related in function and architecture to Boston’s new City Hall, which opened in 1969. The BGSC complex consists of two state office buildings in the brutalist style, using monumental concrete walls and massive angular slabs. In contrast to the open-sided City Hall Plaza, this complex was intended to be more people-friendly, with an enclosed plaza and a more defined shape that generally aligns with surrounding streets. However, the BGSC looms over the intersection of Cambridge and New Chardon Streets and overpowers nearby buildings. At street level, pedestrians face intimidating and unwelcoming entrances. In a promising development, in July 2024, the state announced plans to redevelop the complex, and one of the buildings is already closed. A reconceived BGSC would incorporate housing, mixed-use commercial space, and redesigned plazas and entrances to integrate better with the neighborhood.

Diagonally across the square, there has already been an attempt to bring back the human scale. On the former site of the Bowdoin Square Firehouse, the Leverett Saltonstall state office building opened in 1965. Its International Style architecture was simple and streamlined compared with the Government Service Center, although the concrete plaza in front was not particularly welcoming to visitors. In 1999, the Saltonstall Building was closed to clean up asbestos and reconstruct its ground-level areas. The design goal was to fill in the plaza and help revitalize Cambridge Street. Upon reopening, the 2004 addition included five stories of wraparound brick floors at street level, containing a mix of market-rate condos, affordable housing, and retail space. (The building is now privately owned and called 100 Cambridge Street.)

Today the name “Bowdoin Square” is largely lost. The Bowdoin MBTA station is most people’s only exposure to the historic name. What remains of the square is little more than a soulless intersection. Still, Bowdoin Square’s evolution over centuries exemplifies the history of the West End and of Boston as a whole, through prosperity and decline and attempts at revitalization.

Article by Christina Horn, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Art Deco Society, “New England Telephone and Telegraph Company”; Atlas of the City of Boston: Boston Proper (Bromley, 1898, 1922, 1938); Boston Globe (March 27, 1922; March 19, 1929; November 11, 1930); Bruner/Cott Architects, “Boston Government Service Center: Lindemann-Hurley Preservation Report,” January 2020; Commonwealth of Massachusetts, “Charles F. Hurley Building Redevelopment”; David Kruh, Always Something Doing: Boston’s Infamous Scollay Square (Northeastern University Press, Rev. Ed., 1999); Leventhal Education & Map Center, Atlascope; National Park Service, “Site of the Revere House Hotel”; Nancy S. Seasholes, ed., The Atlas of Boston History (University of Chicago Press, 2019); Joan E. Smith, Urban Renewal and the West End (Boston Redevelopment Authority, 1992); Urban Land Institute, “ULI Development Case Studies: 100 Cambridge Street/Bowdoin Place,” 2006; The West Ender (April 1986).