Chinese Laundries in the West End

Chinese immigrants owned and operated laundries in the West End during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an under-emphasized aspect of the historic neighborhood’s multi-racial and multi-ethnic diversity.

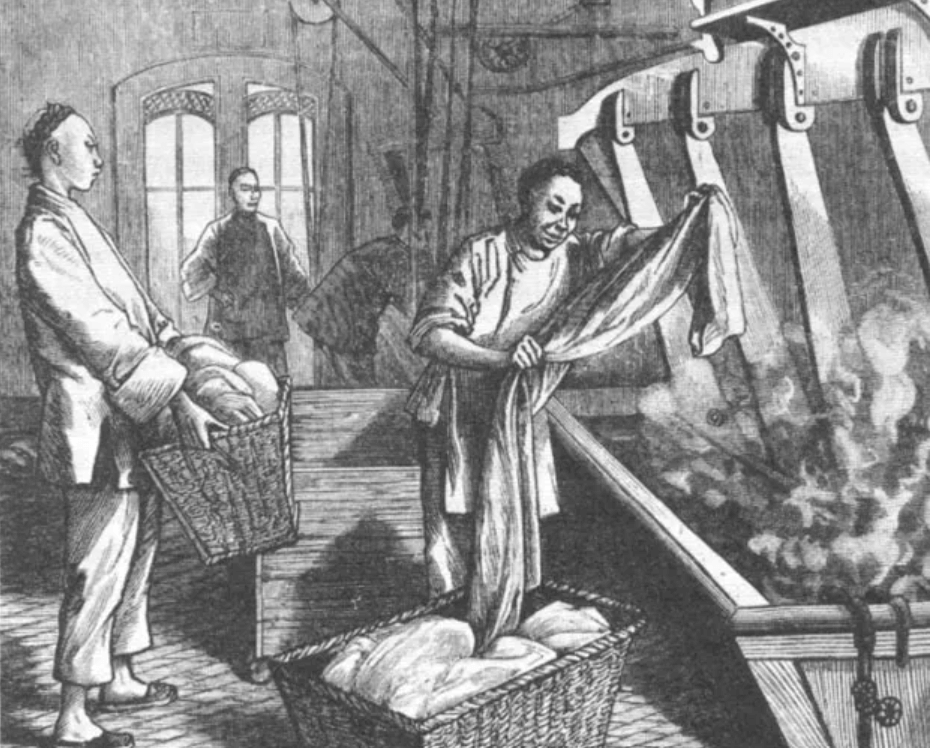

Since the mid-nineteenth century, Chinese immigrants, many of whom were men, settled in New England in order to earn money for their families back in China. Nativist backlash to Chinese labor in construction and manufacturing, in Boston but especially on the West Coast, culminated in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which prohibited virtually all Chinese workers from immigrating to the United States (until the law’s repeal in 1943). Chinese immigrants already in the US faced preexisting discrimination that denied them opportunities to work in most professions. One of the limited options available to Chinese men was the operation of laundries in many of Boston’s neighborhoods. In 1879, Boston had just 120 Chinese residents, and 100 of them worked for 40 different laundries; 10 of those laundries (25%) were in the West End. Chinese laundry owners usually had residences in the buildings where they washed and dried clothes, which meant many of them called the West End their new home.

Chinese laundries in Boston required only a modest initial investment and minimal English language skills. The laundries offered cheap services to city dwellers who found laundry work difficult, especially if they lived in crowded housing. But as Chinese men were confined to laundry service in a racist labor market, this work also reinforced racist stereotypes of Chinese men as effeminate. Laundry was widely understood as “women’s work,” even in China, and so whites in the United States often perceived Chinese men not only as “womanly” but also, related to cleaning clothes, “dirty.”

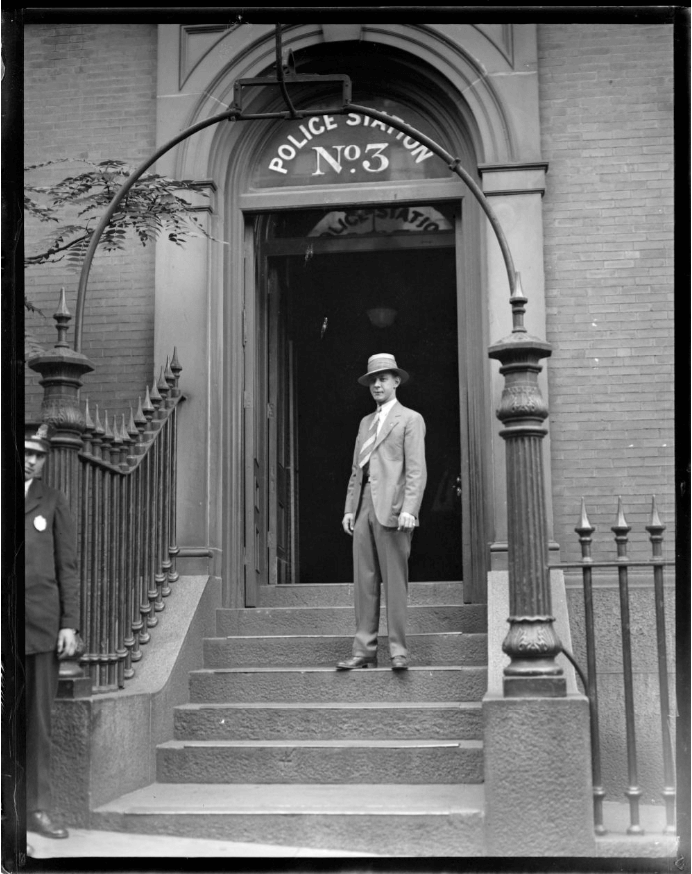

The West End’s Chinese population in 1890 was large enough that it merited a visit from the aldermen of Boston to “the Chinese quarters in the West End.” The city councilors met up at the Joy Street police station, which was “considered the most complete station in the city.” Walking through the West End, the aldermen visited a laundry owned by Sing Lee on the corner of Howard and Bulfinch Streets, the tea importers of Hop Yum & Co. on Howard Street, and an opium den on an unnamed street. They found that Sing Lee’s laundry was “in very good condition, and not a sign of anything other than an active set of laundrymen was found.” They commended the “progressive merchants” of Hop Yum & Co. for a “tastefully painted shingle” outside their building on 39 Howard Street. The councilors finally visited a Chinese social club on Howard Street, which boasted “charter members” including “some illustrious pugilists and sports.” Yet despite these words of praise, the Globe reiterated the aldermen’s resort to racist stereotypes after inspecting the West End’s Chinese enclave: “It was plain that it was useless to visit any more places, as the sons of the Flowery Kingdom were, in the language of the street, ‘dead on.’”

Chinese laundries in the West End, as in other neighborhoods, were often sites of burglaries and the occasional murders of laundry owners. On July 25, 1898, the Boston Globe reported that police officers from the Joy Street station were looking for a “colored man” they suspected to have robbed and stabbed Sing Lee at his laundry on 90 Cambridge Street. Lee was asleep in the back room of his laundry, and he leapt from his bed after awakening to the burglar moving towards the cash drawer. After Lee was stabbed in his back and seriously wounded, he was soon brought to Massachusetts General Hospital. On August 9, 1899, the day after three young men robbed Yen Tan and his laundry in the South End, authorities suspected the next day that the “method of last night’s job [in the South End] was similar to that of the West End one,” at a Chinese laundry on 38 Causeway Street.

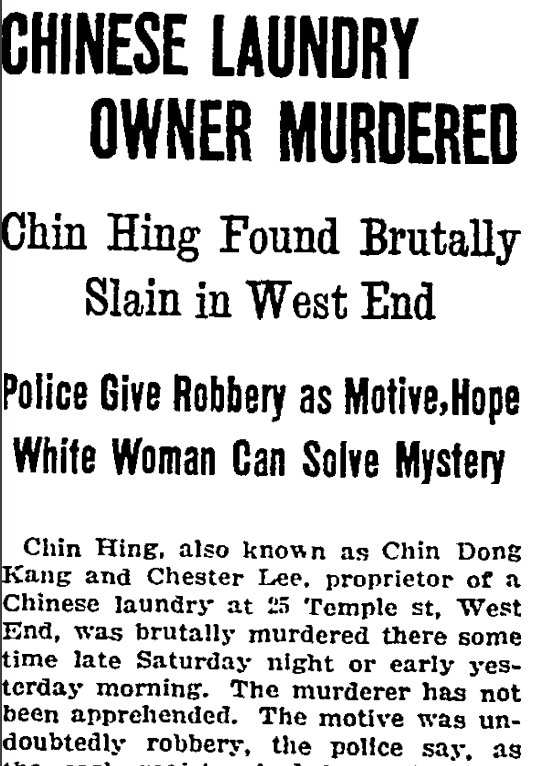

The murder of West End laundry owner Chin Hing, around January 26-27, 1918, received the most press attention. Chin, who also went by Chester Lee and Chin Don Kang, ran a laundry at 25 Temple Street in the West End. Police found Chin Hing murdered and lying on the backroom floor with the cash register emptied. Harry Goodsnider, an errand boy who lived on 36 Staniford Street, saw the door left open and stepped inside the laundry to investigate. Goodsnider swiftly ran to the Joy Street police station to notify the authorities. The Globe reported that “Chin Hing has conducted the laundry for four years and was well known and liked by his 200 or more customers.” Chin Hing was also the cousin of Charles K. Shue, the first Chinese-American justice of the peace in the United States; Shue lived in Chinatown, on Harrison Avenue. The following day, Goon Lee, a Chinese laundry operator from East Cambridge, was arrested at the Joy Street station and charged with Chin Hing’s murder. Goon Lee was “a close friend of the dead man” but “said to have denied all knowledge of the murder.” Chinese community leaders declared that Chin Hing was likely murdered by a white man. Mary Barrows Lee, a white woman from Roxbury, claimed to have married Chin Hing in Providence eleven years prior, and claimed his estate – including the laundry business and a $2,500 life insurance policy. West End residents recalled frequent visits by Lee to Chin’s shop, where he would give her gifts or money. On February 8, 1918, the murder charge against Goon Lee was dropped.

The deaths of Chinese laundrymen in the West End became the subject of rumors throughout the neighborhood. On May 22, 1922, Yee Gon Bo, a 42-year-old Chinese laundry operator, was found dead on the floor of his shop on 129 Chambers Street in the West End. Michael Lewis, who resided on 58 Leverett Street in the neighborhood, discovered Yee’s body while passing by and reported what he saw to the Joy Street police station. “Residents of that vicinity” around Chambers Street suspected a murder, though police determined that Yee died of natural causes and could not ascertain a motive for anyone to kill him. Yee Gon Bo, before his death, immigrated to the US in 1912 (evading the Chinese Exclusion Act’s restrictions), had a wife living in China, and a relative named Yee Wing who lived on 17 Lyman Street in the West End.

Chinese laundries in the West End were not always sites of tragedy. On May 1, 1936, Abraham Goldstein, a Dorchester native who ran a tailor shop on 37 Howard Street, fled his shop as a fire broke out inside due to an “explosion of cleaning fluid.” Goldstein ran outside instantly instead of covering himself with any suits in the store, and soon became a “human torch.” Despite sustaining many serious burns, his life was saved by Terry Tobin, a Boston attorney who saw Goldstein after turning the corner from Scollay Square. Tobin saw residents struggling to take off Goldstein’s coat and stop the flames, and so he threw his own coat around Goldstein to finally put out the fire. Tobin recalled, “We took him then into a Chinese laundry next door and wrapped him in a blanket.” Goldstein apparently tried running back into the shop and had to be restrained, but Tobin felt relieved to have intervened: “But what difference does a suit make, when a man’s life may have been saved.” The fact that a Chinese laundry on Howard Street served as a safe place during a life-threatening emergency demonstrated how common and familiar the laundries were to the neighborhood.

The extensive history of Chinese businessmen operating laundries in the historic West End reflects not only the cultural, legal, and economic obstacles that Chinese immigrants faced throughout the country, but also an under-emphasized story of the West End’s multi-racial and multi-ethnic diversity.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: University of Victoria; Sampan; National Park Service; ProQuest (“Aldermen On A Junket,” Boston Globe, April 20, 1890; “Burglar Stabbed Sing Lee,” Boston Globe, July 25, 1898; “Gun At His Head,” Boston Globe, August 9, 1899; “Chinese Laundry Owner Murdered,” Boston Globe, January 28, 1918; “Charge Chinaman Murdered Friend,” Boston Globe, January 29, 1918; “Widow Seeks Estate of Slain Chinaman,” Boston Globe, February 8, 1918; “Chinese Found Dead in West End Shop,” Boston Globe, May 23, 1922; “Lawyer Saves Human Torch,” Boston Globe, May 2, 1936)