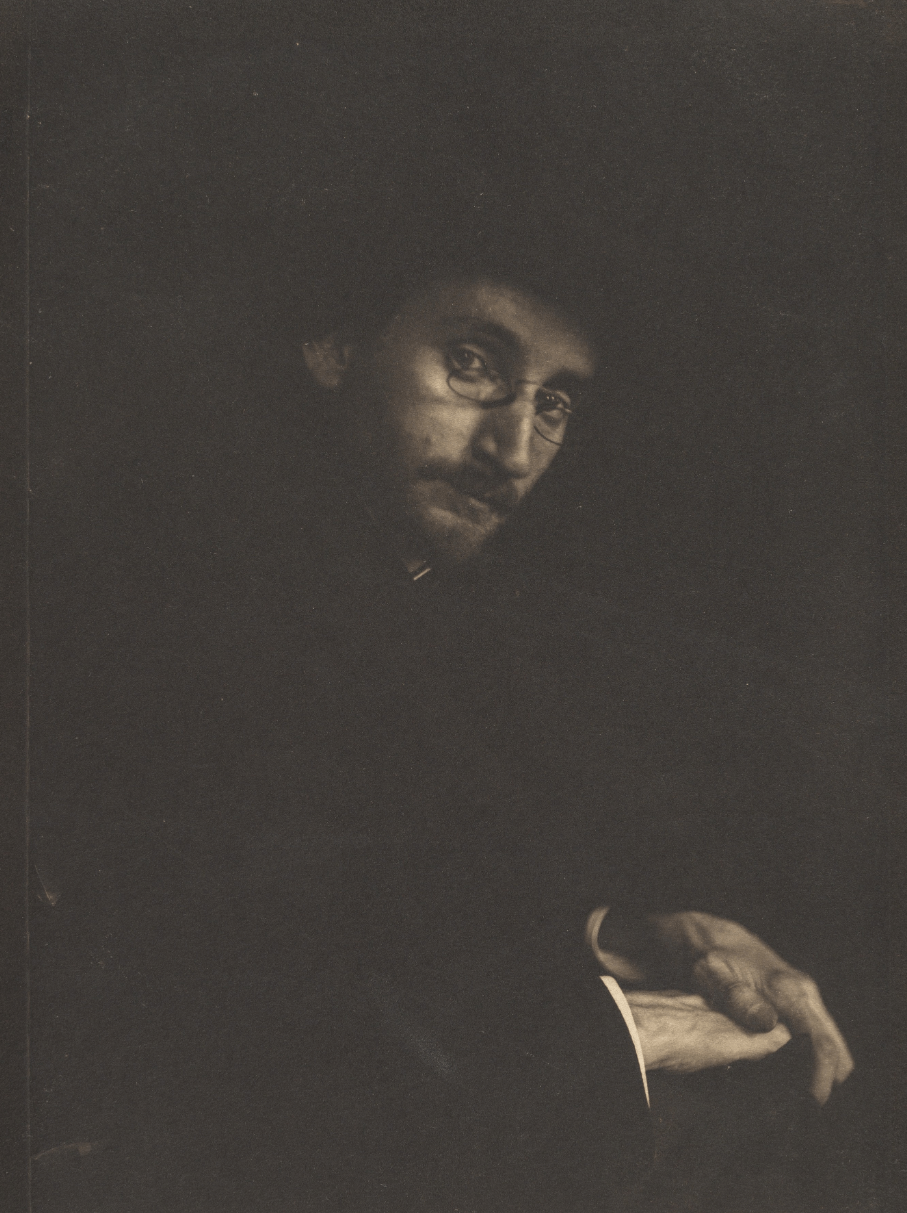

F. Holland Day

F. Holland Day was a publisher and photographer who lived in the historic West End around the turn of the 20th century. Though he never described himself in so many words, he may have had same-sex relationships with other men and is generally seen as traveling in LGBTQ+ circles during his life. In addition to his significance as an artist, he also had a close relationship with an Italian immigrant family, the Costanzas, from the Upper End of the West End while he lived on the north slope of Beacon Hill.

Fred Holland Day was born in 1864 and raised in Norwood, Massachusetts. He was his parents’ only child and his family was fairly wealthy. In 1888, he began volunteering at the Parmenter Street settlement house in the North End. Around this time, he also joined a social group called the Visionists, led by architect Ralph Adams Cram, who were interested in theosophy, Aestheticism, and medieval tradition. Both of these activities were influential on Day’s later work.

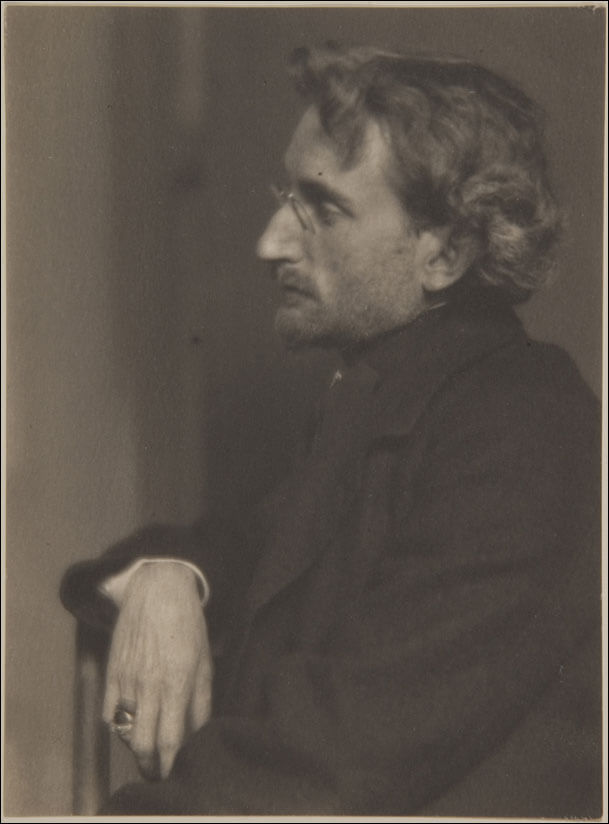

Day became a resident of the West End in 1894 when he moved into an apartment at 9 Pinckney Street on the north slope of Beacon Hill. A novelist named Alice Brown lived in No. 11 and had a relationship with a poet named Louise Imogen Guiney, who had been close friends with Day before his move to the Hill. For Guiney, work and pleasure were near at hand on Pinckney, as she worked for Copeland & Day (Day’s publishing firm which he ran with his friend Herbert Copeland) and modeled for photographs to encourage Day’s burgeoning passion. With Copeland & Day, the two men hoped to run a publishing firm to rival William Morris’ Kelmscott Press in England, focusing on the aesthetics of the book as much as on the quality of the text itself. They published controversial and unconventional works, including Guiney’s subversive Catholic poetry and the first American edition of the English translation of Oscar Wilde’s play, Salomé (1894).

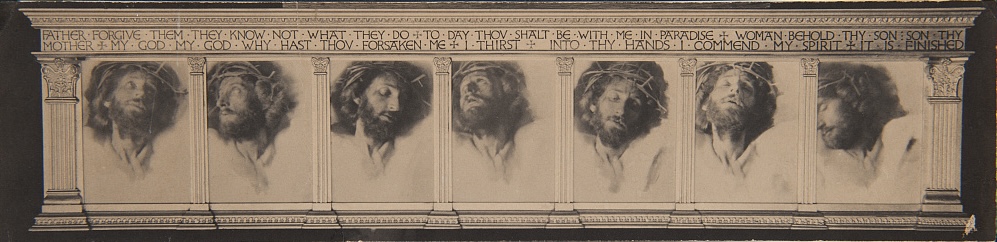

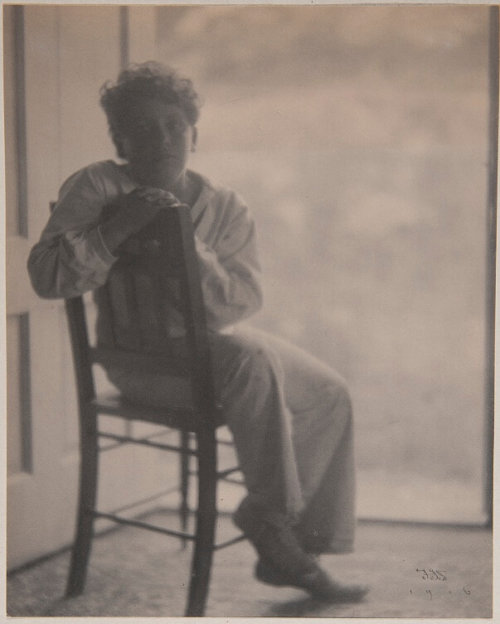

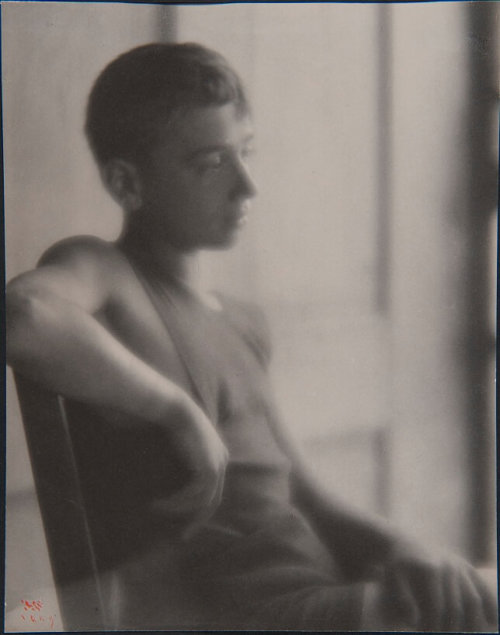

In the same vein, F. Holland Day’s photography of this time also pushed back on convention. Day was a Pictorialist photographer – some better known artists in this style are Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen, both friends and rivals with Day. He wanted to create photographs that resembled paintings, rather than recreating real life. Day used elaborate costumes and set-dressing to achieve this look, as well as manipulating the plates that the photos would be printed on to make the images fuzzier and softer. He preferred religious and historical subject matter, posing his friends, acquaintances, and even himself, as figures from the Bible and ancient history. He is best known today for a work called The Seven Words, a series of close-up self-portraits depicting Christ on the cross. He held a viewing party for this work and several other Biblical images in November 1898 at his apartment on Pinckney Street, inviting even the nuns from Louisburg Square to voice their opinions. The reception of the works was largely positive, though his work was never free of controversy.

Day’s photography was also controversial for other reasons. He was known for his male nude portraits, which some art historians consider indicative of his possible homosexuality when taken into consideration among the other facts of his life. We have very little concrete evidence of Day’s sexual preferences in so many words, so many historians shy away from making statements with little definitive proof. Still, because he is shrouded in mystery, it is important to acknowledge that there is more depth to him than meets the eye. Day traveled in social circles among men accepted as queer today, including his business partner Herbert Copeland, who wrote letters to Day about his own romantic attachments to married men, and Day’s personal and professional relationships with Oscar Wilde and Aubrey Beardsley. There is some speculation that letters sent between the latter two and Day confirm that Day was gay, though the actual existence of these letters is unproven. Day never married and did not have any children, and his family home is now the headquarters of the Norwood Historical Society, who hold sway over how Day is portrayed. Questions about Day’s sexuality have not been fully explored.

Day prioritized using diverse models for his photographs and he ventured into the neighborhoods around Pinckney to find them. In the earlier part of his career, he rarely took portraits of people as themselves – he was far more interested in recreating historical, mythological, and religious figures. He mentored a young Khalil Gibran as he dabbled in art (he is now better known as the author of The Prophet). Day also used Black models when he wanted to portray historical subjects from Africa. While these photos do contribute to the exoticizing of Black people as “other,” Day did photograph them skillfully and used media where the nuances of Black skin could shine. Day also gave these photographs exalted positions, using a photo of a Black model dressed as an African king in the place of Christ in an 1898 triptych called Armageddon. Day often nurtured close relationships with the models he used, sometimes taking on the role of “uncle” for an entire family as he did for the Costanzas of the West End.

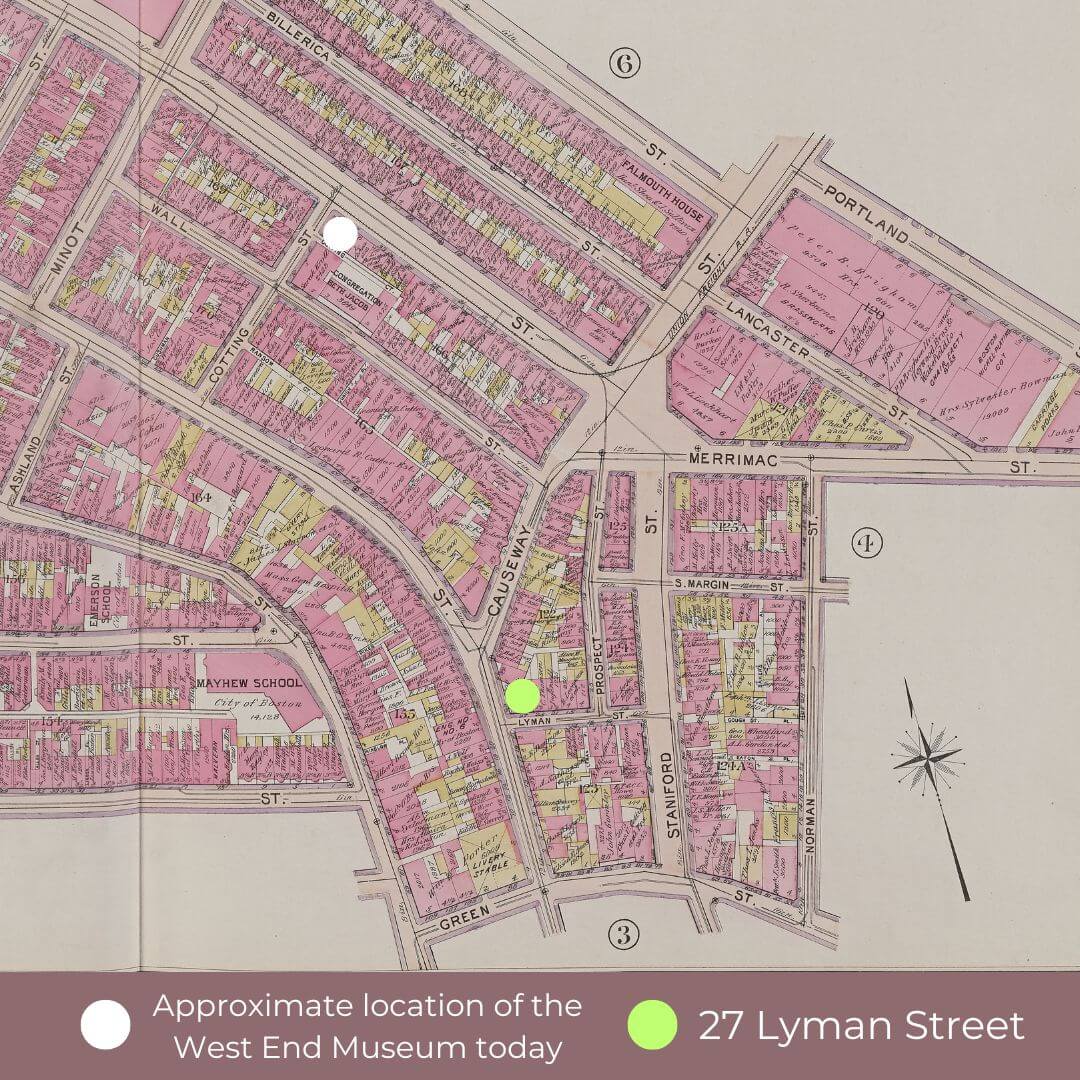

Pasquale and Concetta Costanza emigrated to the United States from Italy in 1881 with their infant son Enrico. They settled in Boston, where their second son, Vincenzo, was born on October 5, 1882, in the North End. Their next six children were born at various addresses between the North End and the West End from 1884 to 1897. In the 1900 United States Census, they are listed as living at an address on Lyman Street, where they appear to have settled for perhaps the next 15 or so years. Lyman Street connected Staniford Street to Leverett Street. Lyman and Leverett were both demolished during urban renewal in the late 1950s.

The Costanza children were:

- Enrico (Henry) born in 1880 in Italy

- Vincenzo (Vincenzino or Vincent) born in 1881 in the North End

- Maria Giovanna (Maria or Jennie) born in 1884

- Amato Antonio born in 1887 in the North End

- Armelindo (Mellie) born in 1889 in the West End

- Pasquale Jr. (Pucky) born in 1891 in the North End

- Ciriaco (James or Chuggy) born in 1892 in the West End

- Antonio (Tony) born in 1895

- Giuseppe (Joseph or Pippy) born in 1897 in the North End

During one of their earlier stays in the West End in 1893, tragedy struck the Costanza family when their son Amato Antonio died at only age 7. At the time, the family was living on Lyman Place, a small alley off of Lyman Street. He fell off the roof of their apartment building and fractured his skull. Though they moved back to the North End shortly after this event, it did not prevent them from eventually settling back into the same block in the West End later. In 1905, their only daughter, who had gotten married in 1901 at age sixteen, died in childbirth. Her baby was born premature and also died three months later. Though it appears that she and her husband lived outside of Boston, her baby John was taken to the Massachusetts Infant Asylum in the West End when he became gravely ill, and it was there that he passed at three months old. The rest of the boys survived childhood, though many started working as errand and newsboys when they were fairly young, indicating that the family was desperate for a larger income than Pasquale Sr. could provide as a shoemaker. After the eldest son Henry (Enrico) married, his family lived alongside his parents and brothers under the same roof.

The historical record is cloudy on how F. Holland Day may have met the Costanza family, but he spent Christmas Day 1903 at their house on Lyman Street. From then on, they remained remarkably close. Concetta and Pucky spent some weeks the next summer at Day’s property in Maine. Through the years, Pucky and his younger brothers regularly repeated these visits, including sometimes traveling in winter as well as summer. Day took many portraits of Pucky, Chuggy, Tony, and Pippy, some of which were exhibited in a gallery show in Buffalo, New York, in 1914. The Costanza family kept these photographs in their family scrapbook albums. The relationship between the brothers and Day remained close until Day’s death in 1933, though letters became the primary medium for communication as he retreated from social life. The Costanzas wrote to Day seeking advice when they were in trouble and for his approval of their girlfriends and future wives. Their descendants maintain that Day was a “true friend” to the Costanzas.

The Costanzas appear to have largely moved out of the West End before the period of urban renewal. Pasquale Sr. died in 1923 of pneumonia in the home the family had moved to on Staniford Street. The eldest son, Henry (Enrico), died suddenly in 1925 from chronic heart problems – he was only forty-five – leaving his wife and six children. Most of the sons appear to have moved out of the West End upon their marriages – or at least to areas like the north slope of Beacon Hill which was not demolished. F. Holland Day had moved out of his apartment at 9 Pinckney Street by 1909. He lived at his property in Maine for many years and then moved to his family home in Norwood, MA, to care for his elderly mother. He gave up photography around the beginning of World War I, when the cost of materials skyrocketed. Though he kept up with correspondences for the rest of his life, he became somewhat of a social recluse, often discouraging visitors, including the Costanza brothers, from coming to see him. He died on November 6, 1933, leaving behind no children or close relatives. F. Holland Day largely fell out of the art historical canon due to his withdrawal from society, his rivalry with Alfred Stieglitz, and a devastating fire in 1904, but his work has seen somewhat of a revival in recent years, especially in Boston.

Article by Emma Beckman, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Allen Ellenzweig, “Defending F. Holland Day’s Gayness,” The Gay & Lesbian Review Worldwide 16, no. 5 (September 1, 2009): 8-9; Patricia J. Fanning, “F. Holland Day and ‘the Beautiful Boy’: The Story of Thomas Langryl Harris and Day’s Nude Study,” History of Photography 33, no. 3 (June 29, 2009): 249-61; Patricia J. Fanning, Through an Uncommon Lens: The Life and Photography of F. Holland Day (University of Massachusetts Press, 2008); Estelle Jussim, Slave to Beauty: The Eccentric Life and Controversial Career of F. Holland Day, Photographer, Publisher, Aesthete (Boston: Godine, 1981); The Metropolitan Museum of Art, “F. Holland Day with Model.”

1 Comment