F. O. Matthiessen

F. O. Matthiessen was a literary critic and Harvard professor who lived in the historic West End from 1939 until his death in 1950. His life and work were heavily influenced by his identity as a gay man and his twenty-year relationship with the artist Russell Cheney, even though they were, for all intents and purposes, secret. Matthiessen is credited with founding the discipline of American Studies, and his major works explore key figures of nineteenth-century American literature through the historical context that shaped their writings.

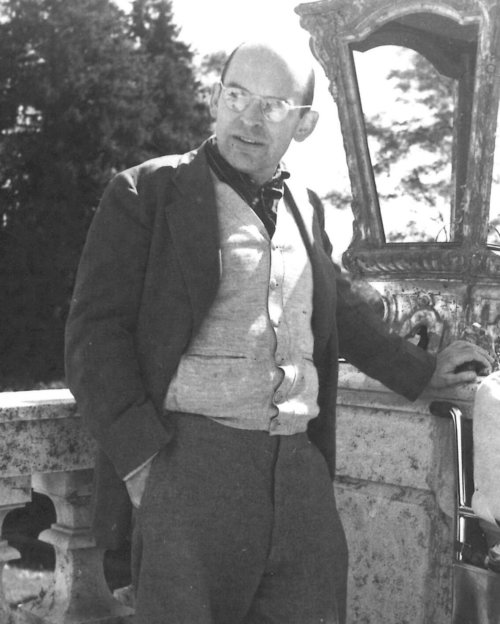

Francis Otto Matthiessen was born in Pasadena, California, in 1902. He graduated from Yale University in 1924, was a Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, and attended graduate school at Harvard University with degrees conferred in 1926 and 1928. He began teaching at Harvard in 1929 and was appointed to a full professorship in 1942. He was resident professor at Eliot House on Harvard’s campus, and they still maintain a library room of manuscripts and books from his professional research collection. In his youth, Matthiessen had a close relationship with his mother, but his father was largely absent. Matthiessen attributed this, in part, to the development of his sexuality as a wish to fill “the empty space where my father should have been.”

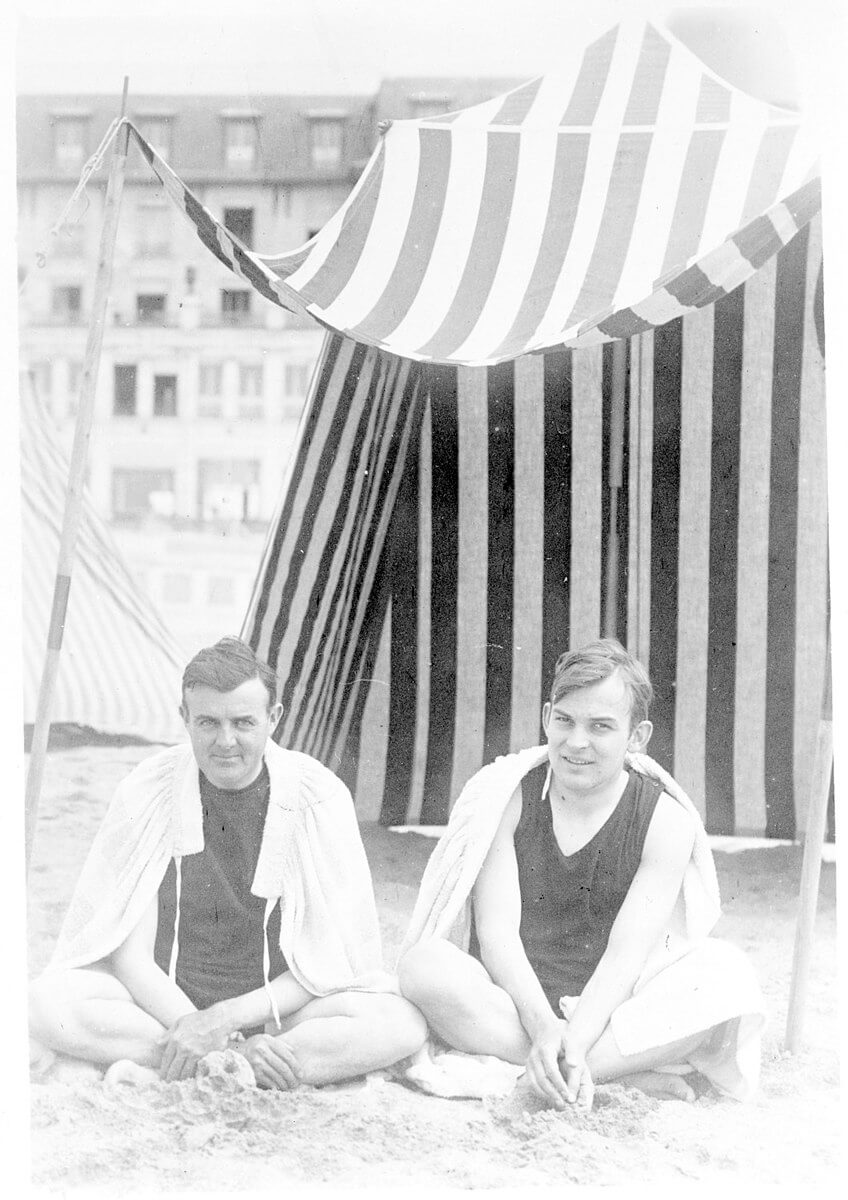

Matthiessen met the artist Russell Cheney on the ocean liner “Paris” in 1924 as they were both traveling to Europe: Matthiessen to continue his studies at Oxford and Cheney on his way to Italy to paint. Matthiessen had had homosexual experiences before then, but his budding relationship with Cheney made him feel confident in his sexuality and willing to embrace the potential for happiness with another man. From the beginning, they wrote each other nearly every single day they were apart, resulting in thousands of letters over their twenty-year-long relationship. In August 1925, Matthiessen wrote to a friend that his relationship with Cheney was:

…intimate and all-embracing…the central fact remains that Rat [Cheney] and I are so constituted by nature that our two lives and personalities have blended into a harmony of understanding affection which brings us each closer to the other than we have ever been to anyone else. I did not know that life contained anything so right and deep.

In later letters written to Cheney himself, Matthiessen likened their relationship to a marriage between a man and a woman. It was Cheney who encouraged Matthiessen to pursue nineteenth-century American literature throughout his career. For most of their time together, they shared a home in Kittery, Maine, when Matthiessen was not at Harvard and Cheney was not traveling to paint. While their close friends knew that they were more than roommates, Matthiessen diligently protected his privacy at work. He knew that being out at Harvard would bring punishment and demotion. Still, it was generally known that he was not straight and the influence of his sexuality on his academic study is tangible. While he refrained from allusions to homosexual behavior in his books due to the risk of backlash, he wrote about many people who have been the subject of queer studies in the modern day, including Walt Whitman, Nathaniel Hawthorne and Herman Melville, Henry and Alice James, and Sarah Orne Jewett. Still, there were incidents that must have been awkward for Matthiessen, such as when Oxford University Press extended an invitation to a dinner celebrating Matthiessen in 1943 to his wife, on the assumption that he simply must be married to a woman. After Cheney’s death, Matthiessen compiled a book of the artist’s paintings and letters in which their affection and respect is recognizable, though Matthiessen tried to play it down.

Throughout his life, Matthiessen was also an ardent Socialist. Like his sexuality, his politics caused turmoil in his life, but he was able to express them more openly. He canvassed tenements in the North End on behalf of the socialist ticket in the 1930s, and he was strongly convicted to the belief of solidarity between all types of workers and that no worker was better than any other because of their type of labor. He was elected leader of the Harvard Teachers Union for one year in May 1940. He gave the second nomination speech for Harry Wallace’s Progressive presidential campaign in 1948, and he participated in a panel on writing and publishing chaired by W.E.B DuBois attended by over 800 people at the Cultural and Scientific Conference for World Peace in New York in 1949. Despite Senator McCarthy’s claims that homosexuals were especially vulnerable to the Communist cause because they could easily be blackmailed, Matthiessen was adamant that he was making a conscious intellectual choice in committing to Socialist ideals.

On December 26, 1938, Matthiessen was hospitalized for a nervous breakdown. He was deep in working on his most notable work, American Renaissance: Art and Expression in the Age of Emerson and Whitman (1941) and constantly worried about Cheney relapsing into alcoholism. He was discharged on January 13, 1939, and while hospitalized, he, his therapist, and Cheney created a plan to move into an apartment in Boston to promote his healing. Matthiessen and Cheney could live there together (Cheney was not allowed to live in Eliot House on Harvard’s campus with Matthiessen), and Matthiessen would be less isolated from his friends while he continued writing. Cheney found the apartment for them at 87 Pinckney Street, on the very edge of the historic West End. While they still preferred living in Maine, the apartment on Pinckney became a vibrant second home where they regularly entertained for Christmas and other celebrations—and Matthiessen could continue to work at Harvard with a retreat away from campus. A close friend of Matthiessen, Harry Levin, reflected later that Matthiessen and Cheney were able to live more openly in their apartment on Pinckney than they had before. Many of their friends who knew they were gay and accepted their relationship lived nearby on Beacon Hill.

Russell Cheney died at home in Kittery on July 12, 1945. His long struggle with alcoholism was a burden on their relationship, but Matthiessen stayed by his side. Cheney was twenty years older than Matthiessen, and the fact that Cheney would likely die before Matthiessen was a source of constant worry, as it would be for any committed partners. Due to the nature and secrecy of their relationship, however, Matthiessen was unable to properly grieve his loss, which must have been a burden on his already fragile mental health. Matthiessen continued living at 87 Pinckney Street after Cheney’s death, and increased his Socialist activism, traveling across the United States and abroad to give lectures on literature and politics.

In early 1950, Matthiessen returned to Boston after spending some time away in Maine writing. On Friday, March 31, 1950, he checked in at the Hotel Manger in the West End—now demolished. There is speculation that he chose this location because it was located far away from the homes of his friends on Beacon Hill, and that the geographic location of the hotel held important symbolism for Matthiessen, as North Station was the gateway to his beloved Maine. Despite the historic borders of the neighborhood, Matthiessen apparently did not conceptualize his address at 87 Pinckney to be truly part of the West End. Perhaps he was influenced by the burgeoning rhetoric that the West End was a “slum.” After spending the evening at the house of his friend and colleague Kenneth Murdock in Beacon Hill, he returned to the Hotel Manger, where he died by suicide by jumping out of a twelfth-story window. In a note found in the hotel room, he claimed that he had come to this decision based on despair over the state of the world; later analysis suggests that vitriol over his leftist politics—and therefore, insinuations and threats over his sexuality—was also tied to his despondency at that time. Despite his premature death, much of his work remains highly influential in the study of American literature today—especially on Walt Whitman, T.S. Eliot, William and Henry James, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. Though his work is rightly criticized for largely excluding women, authors of color, and anyone outside of New England, he cemented nineteenth-century Americans—many of them queer-leaning in their own right—in the global literary canon.

Article by Emma Beckman, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Scott Bane, A Union Like Ours: The Love Story of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney (University of Massachusetts Press, 2022); Ed Folsom and Kenneth M. Price, “Biography,” The Walt Whitman Archive; Randall Fuller, “Aesthetics, Politics, Homosexuality: F. O. Matthiessen and the Tragedy of the American Scholar,” American Literature 79, no. 2 (June 1, 2007): 363–91; Louis Hyde, ed., Rat & the Devil: Journal Letters of F. O. Matthiessen and Russell Cheney (Hamden, CT: Archon Books, 1978); Harry Levin, “The Private Life of F.O. Matthiessen,” The New York Review of Books, July 20, 1978; LIFE, “Red Visitors Cause Rumpus,” April 4, 1949; The Harvard Crimson, “Eliot Book Room Exhibits Treasures,” February 19, 2002; The Harvard Crimson, “F. O. Matthiessen Plunges to Death from Hotel Window,” April 1, 1950; The Harvard Crimson, “Matthiessen Heads Union,” May 16, 1940.