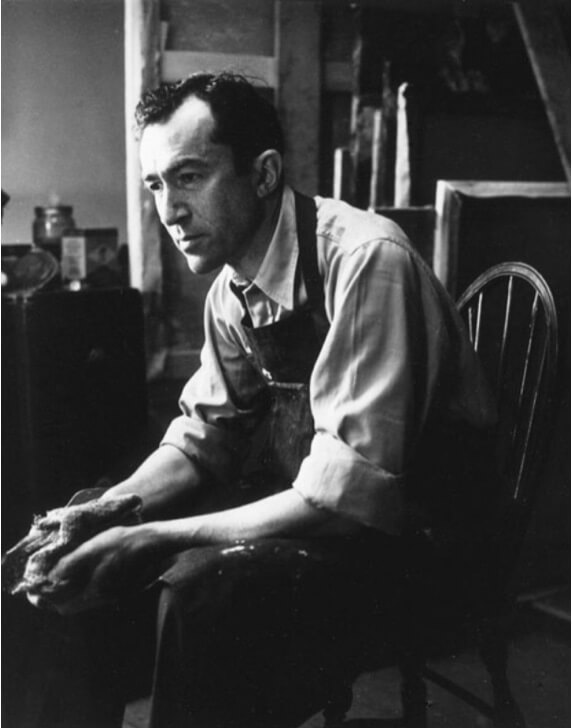

Hyman Bloom

Hyman Bloom was a Latvian immigrant to the West End who become the first Abstract Expressionist. His work features powerful – often morbid – themes juxtaposed with bright colors to create striking works of art.

Hyman Bloom (1913-2009) is one of Boston’s most renowned painters and a true West End gem. Artists Jackson Pollock and Willem de Kooning called him “the first Abstract Expressionist,” and his work has been exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, the Young Museum in San Francisco, and most recently at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston (MFA).

The artist’s dedication to his home in the West End was both the making and breaking of his career. But while Bloom is often overlooked in the chronicles of art history, the subject matter of his work still resonates greatly with people today.

Born in Latvia, Bloom came to Boston with his family as a child in 1920, settling in the West End. The neighborhood helped shape his early life, as it not only guided his rise in the art world, but also influenced the themes which would interest him for years to come.

Bloom’s parents raised him in the Jewish faith, which inspired some of the imagery he used in his later paintings despite not being overly religious himself. His father Joseph worked in the leather business, and his mother Anna as a seamstress. The youngest of three, Bloom’s older brothers, Samuel and Morris, immigrated to America before the rest of the family. The West End was home to many Jewish immigrants in a time when anti-Semitic sentiment was high in Boston. As a teenager, Bloom witnessed violence and discrimination brought on by Irish-Catholics in the area inspired by the words of Father Charles E. Coughlin and his Christian Front movement.

As a youth, Bloom prospered in his art, including at the Washington Junior High School in the West End. His eighth-grade teacher Mary Cullen recommended him for a scholarship to a program at the MFA. Additionally, Bloom enrolled in drawing classes at the West End Settlement House under the tutelage of painter Harold K. Zimmerman.

Bloom was only 28 years old when then MoMA curator Dorothy Miller included six of his pieces in her exhibit, “Americans 1942: 18 Artists from 9 States.” Bloom rose to prominence in the 1940s and 1950s when his work focused on the interesting juxtaposition of beautiful colors with morbid subject matters. Even though he distanced himself from his Jewish faith later in life, it is no surprise that the gruesome images of the Holocaust left a lasting impression on him, inspiring frequent corpse imagery in paintings like The Hull and The Bride.

In the midst of Bloom’s success, the art world shifted. George Harold Edgell, the director of the MFA, moved attention away from local artists, and New York City became the place for those artists to be. Resolute in his decision to stay in Boston, Bloom lost the exposure he had enjoyed. His pieces are still displayed in such prominent institutions as MoMA and the Smithsonian, but his name did not become as famous as other Abstract Expressionists, like Pollock and de Kooning, even though they extolled Bloom as the originator of the movement.

Erica Hirshler is the Croll Senior Curator of American Paintings at the MFA and curated the museum’s exhibit “Hyman Bloom: Matters of Life and Death,” which ran from July 2019 through February 2020. She had the rare opportunity to meet Bloom before his passing in 2009 and weighed in on the artist’s legacy. She concurs with others who have described their meetings with Bloom that he was a very private man who would turn his paintings to the wall so guests would not see his unfinished work. She also believes that Bloom’s lack of interest in being in the public eye contributed to keeping him out of later conversations in the art world. Hirshler explained, “Often artists need someone to champion them if they are not pitching all the time themselves.”

Bloom seems to have been more genuinely concerned about his own evaluation of the quality of his pieces than what others thought about them. Luckily, there are those who champion him to this day— like his wife Stella Caralis who contributed greatly to the MFA exhibit — and those who fight to revive his legacy. Be sure to check out Bloom’s work in the MFA’s permanent collection and visit The West End Museum to learn about the place where it all began.

Article by Angelica Dilorio

Source: ArtNews (2); Estate of Hyman Bloom; Jewish Virtual Library; MoMA; WBUR