Hyman Bloom and the West End Community Center

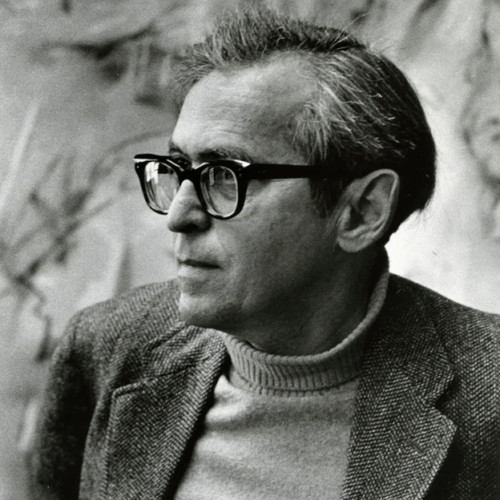

Hyman Bloom is today remembered as a key figure from the Boston Expressionist movement, praised for his mystical and vibrant paintings. Bloom, in addition to being a visionary artist, offers us a window into Boston’s settlement houses in the 1920s and ‘30s. The West End Community Center, and its artist-teacher Harold Zimmerman, nurtured the creativity of a generation of future artists, from Bloom to Jack Levine.

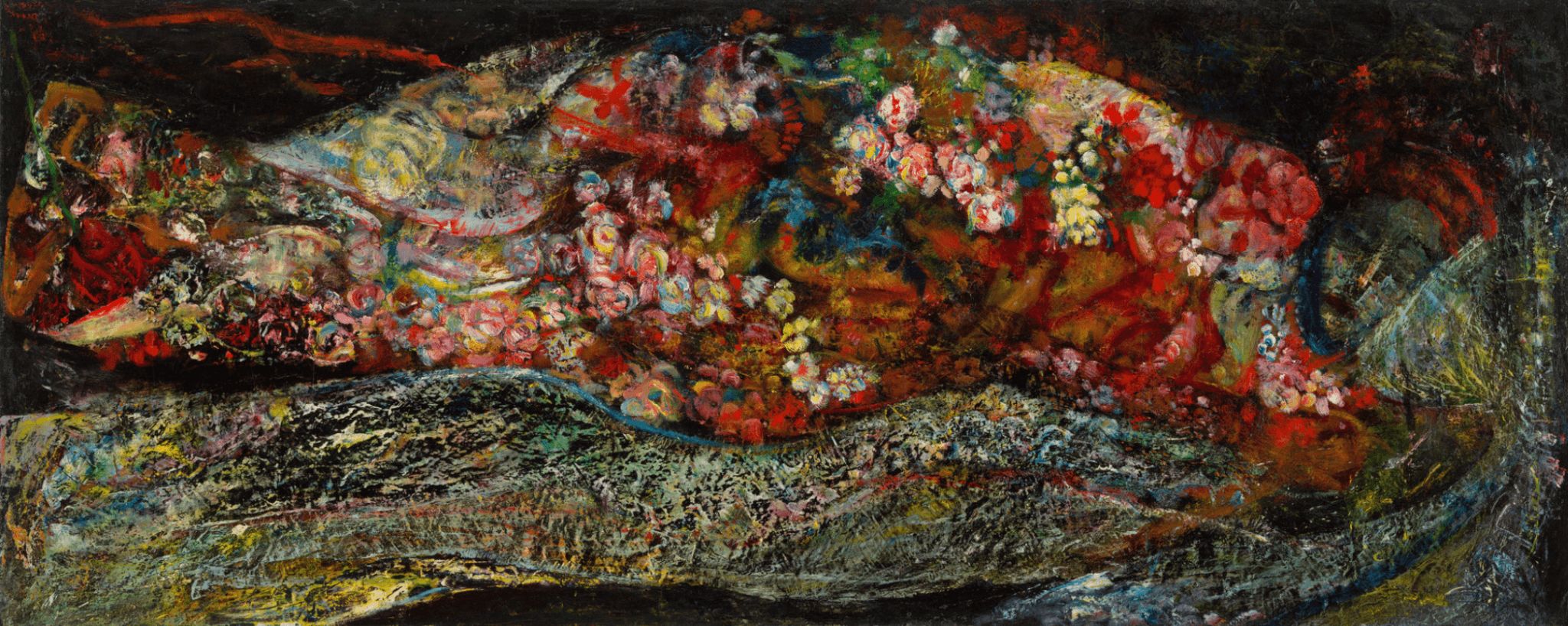

Born in 1913 in Brunavišķi, Latvia, Hyman Bloom immigrated to America at the age of seven. His family, who were Orthodox Jews, changed their surname from Melamed to Bloom upon arriving. Settling into a tenement building at 8 Auburn Street in Boston’s West End, the family crowded eight people into three rooms. Bloom would later become renowned for his animated, mystical imagery; expressive, jewel-toned brushwork; and evocative subject matter, which spanned from cadavers to local synagogues. His long-ranging and celebrated career in the arts would be set into motion in this newfound home, at the West End Community Center.

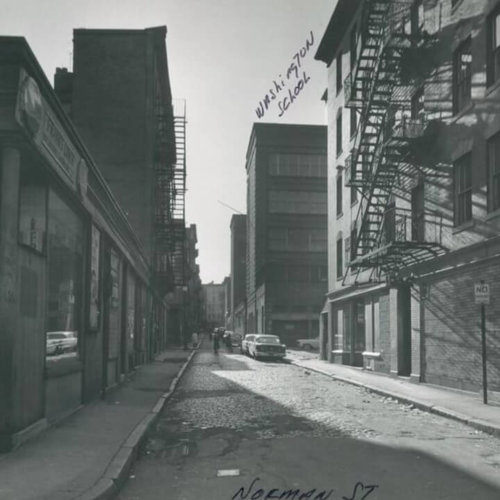

While attending Washington Junior High School in the West End, Bloom’s eighth-grade teacher, Mary Cullen, recommended the fourteen-year-old for a scholarship to take classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which he received. Cullen also encouraged Bloom to attend art classes at the West End Community Center on North Russell Street, believing that the more informal settlement house structure would provide a beneficial counterweight to the rigidity of museum classes. At the community center, Bloom first met and began to study with artist Harold Zimmerman (1905-1941), who would come to have a significant impact on his young pupil’s art and career.

Through the settlement house system, Bloom also met and befriended Jack Levine – born in Boston to Jewish, Lithuanian parents – who himself would become a successful expressionist and social realist artist. Levine began studying with Zimmerman at a settlement house in Roxbury about a year before Bloom joined the system. In an interview with Charles Giuliano in 1986, Levine reminisced about the settlement house system in the 1920s and ‘30s, describing: “Hyman and I excelled. There were branches of settlement houses all over town. Hyman was in the West End and I was in Roxbury. I don’t think it paid Zimmerman much but he was going to the Museum School and needed the money. He had kids drawing on manila paper with pencil and that was it.” Mischa Richter (1910-2001), another immigrant who had recently arrived in Boston after his family fled the Russian Revolution, also joined Zimmerman’s orbit. As he recalled in a 1994 oral history interview: “I stopped drawing, and I was picked up by this guy, Zimmerman… he had Jack Levine and Hyman Bloom under his wing, and he thought very highly of the three of us and never got the credit he should.” Richter would go on to become an acclaimed cartoonist.

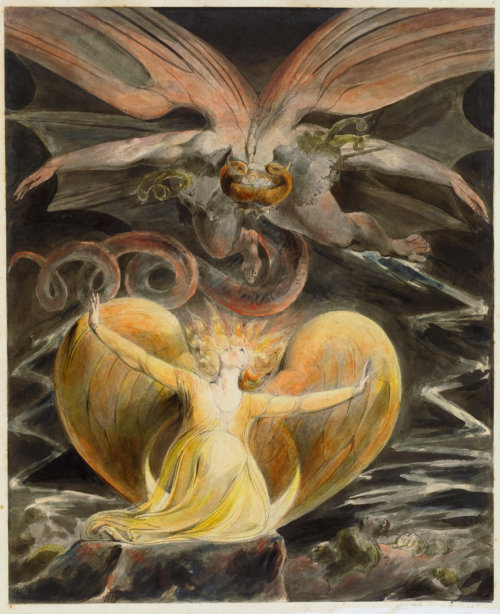

Zimmerman nourished Bloom’s budding talent – and that of other boys at the community center – using an exploratory classroom style. During his classes at the Museum of Fine Arts, under the tutelage of Alma Lebrecht, Bloom was instructed to draw from direct observation, copying models of plaster Greco-Roman casts set before him. Zimmerman’s pedagogy at the West End Community Center was different: students were encouraged to draw from memory, synthesizing different sources and perceptions to express emotion. Bloom was directed to conjure imagined worlds through his drawings, as can be seen in his work Man Breaking Bonds on Wheel (pictured below), which he completed at sixteen. In it, he weaves together various strands of influence: the drawing combines a Michelangelesque attention to musculature and anatomy with a William-Blake-inspired otherworldly, hallucinatory tinge. (Zimmerman was known to have tacked William Blake reproductions on the walls of the community center room.) As Zimmerman had taught him to do, Bloom synthesizes memories – of experiences and different artists’ works – to convey feeling, thereby using art as a way to reflect the spiritual, emotional realm within the material world.

The West End Community Center provided Bloom a vital platform in his nascent artistic journey – a space to experiment and explore. As his friend and classmate Levine would later say:

Everyone becomes an art student too late… the settlement house, without any requirements, was the best way to begin to study art. Hyman was about a year and a half older than me. I began at nine. That’s the time when imagination is beginning to develop, not at college age. No instrumentalist could start training at college age. The artist is a performer, and if you want to do anything you like, you have to start young.

Article by Grace Clipson, edited by Bob Potenza.

Sources: Judith Arlene Bookbinder, Boston Modern: Figurative Expressionism as Alternative Modernism (Lebanon, NH: UPNE, 2005); Bernard Chaet, “The Boston Expressionist School: A Painter’s Recollections of the Forties,” Archives of American Art Journal 20, no. 1 (1980); Charles Giuliano, “Boston Expressionist Jack Levine: Neglected Colleague of Hyman Bloom,” Berkshire Fine Arts (December 2019); Charles Giuliano, “Hyman Bloom and Jack Levine: Legacy of Boston Expressionism,” Berkshire Fine Arts (October 2010); Hyman Bloom: Chronology; Jack Levine, “Jack Levine Talks about the Donation of 108 of His Drawings to the Archives,” Archives of American Art Journal 20, no. 1 (1990); Smithsonian, Oral history interview with Mischa Richter (September 27-28, 1994).