Joseph Lee, Jr.

Joseph Lee, Jr. founded the “Community Boat Club” in 1937 so that West End youth could sail out from the Charles River Esplanade. Community Boating, Inc. was officially incorporated in 1946, and remains the oldest continuously operated public boating organization in the United States.

Joseph Lee, Jr. was born in 1901 to Joseph Lee, Sr. and Elizabeth Perkins Cabot Lee on Beacon Hill. The Lees were one of the aristocratic “Brahmin” families that participated in philanthropic efforts throughout Boston. Joseph Lee, Sr. was considered the “father of the American playground movement,” and Elizabeth Lee was a key player in the American kindergarten movement in the early twentieth century. Joseph Lee, Jr. was no exception, as he shared his family’s dedication to promoting public recreation and belonged to the Outdoor Recreation Committee of Massachusetts. Lee also took a strong interest in the West End’s communities, belonging to the West End Joint Planning Committee. On New Year’s Day in 1937, Lee joined William F. Brophy, a lawyer who worked in the West End, in a creative public advocacy campaign for improving children’s recreational facilities in the West End according to the needs expressed by the neighborhood. One of Brophy and Lee’s demands was for Boston to finally spend the $200,000 that city government set aside, in 1932, for a boathouse at the West End Beach. Joseph Lee, Jr.’s signature contribution to the West End would be in the new opportunities for public boating that he provided to the neighborhood’s children.

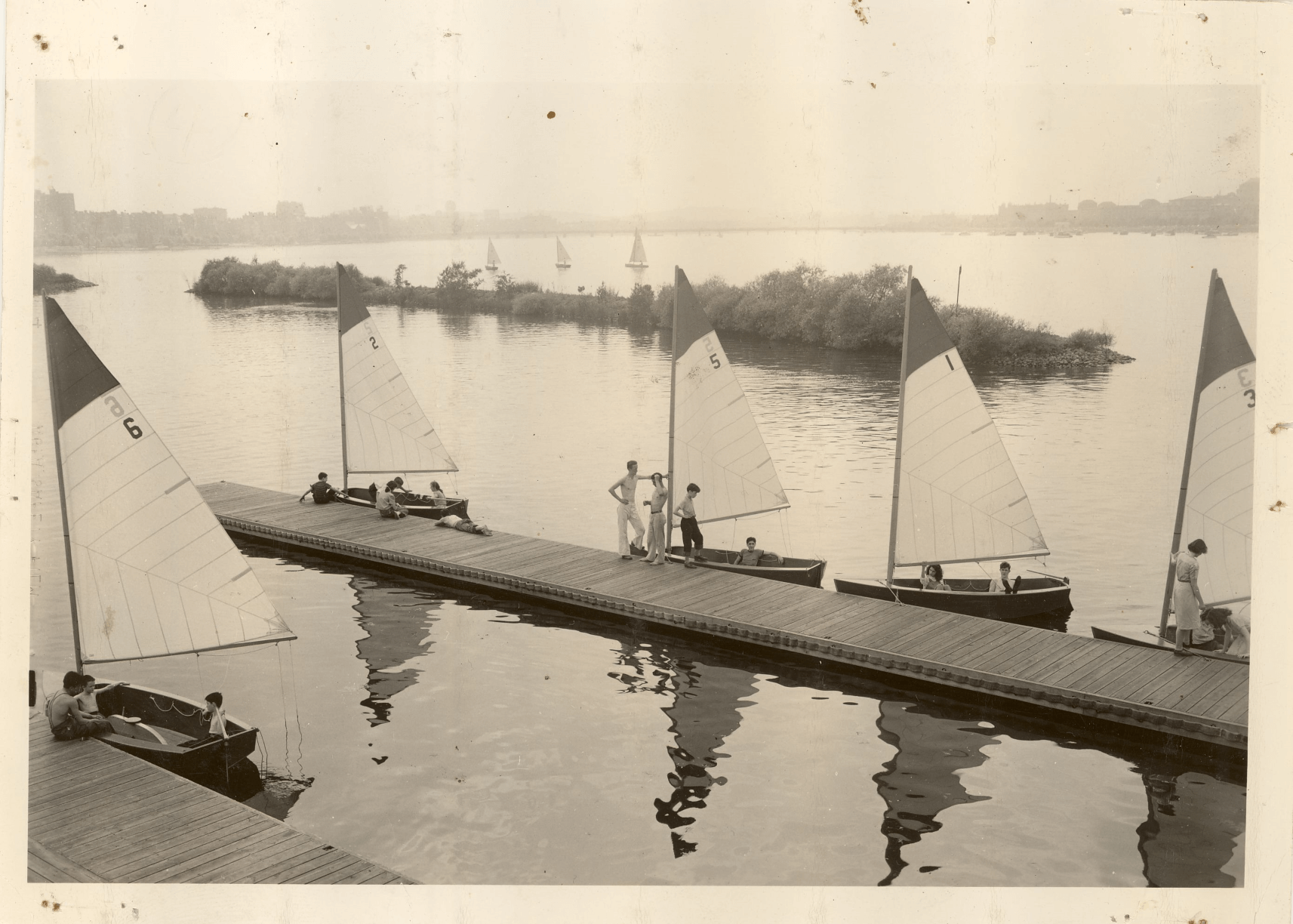

Lee believed that West End children needed an enjoyable outlet away from otherwise hard daily lives in the tenements. To achieve this goal, he designed a simple and relatively inexpensive sailboat for children to assemble with hand tools. One of Lee’s prototypes involved hay bales covered by a tarp and a sail, but the final design was made with pine boards and modeled after a kayak. Lee secured the basement of the West End Community Center as a space for boat building after meeting with the center’s director, John Halko. In 1937, Lee founded the “Community Boat Club” and promoted the organization with flyers sent to all of Boston’s settlement houses. Lee then addressed an assembled group of kids, mostly boys and some girls from the West End, North End, and South End, at the Community Recreation Service building on Boylston Street. He told them that “if you fellows want to learn to build your own boats, I will put up the twenty dollars so you can.” The Community Boat Club began sailing out from the boathouse on the Charlesbank in the summer of 1937, with one-hundred members and seven boats.

The Community Boat Club was not warmly received by the wealthier, elite sailors of Harvard, MIT, and the Union Boat Club on the Upper Basin of the Charles. Boston’s rich believed that the Upper Basin should remain their own domain. Some of that crowd, such as Professor George Owens from MIT’s Pratt School of Naval Design, expressed hope that Lee’s apparently flimsy boats would fall apart before anyone might sail out on them and die. But Lee persisted in improving conditions and opportunities for children to sail. Because the kids were sailing relatively close to the Charles River Dam, which was dangerous, Lee relocated the Community Boat Club’s fleet onto Metropolitan District Commission (MDC) property on the Upper Basin without permission. Lee believed that the city should build a new boathouse there for the West End’s children with some portion of the $1 million gift from Helen Storrow for the improvement of the Charles River Basin. Although Lee’s request was supported by Mayor Maurice Tobin and Helen Storrow herself, Eugene Hultman (MDC director) frequently refused to spend any of the Storrow gift for this purpose. When Hultman demanded that Lee remove his fleet from the Upper Basin, Lee replied, “Why don’t you take it now and smash the boats the kids built last year? You will only break a few hearts.” The hearts of the children of first-generation immigrants in the West End were particularly at stake. One man, Frank Levine, expressed much later that because of the support and opportunity he received for public sailing, “Joe Lee taught me what America could be.”

In 1938, Lee and the Community Boat Club decided to take matters into their own hands through direct action, by regularly sailing under the Longfellow Bridge into the Upper Basin. They even coordinated what one could call a ‘sail-in’ during the Annual American Henley Regatta at the Union Boat Club, and the Community Boat fleet was towed out of the Upper Basin by MDC police who called the young sailors “river rats.” In another protest, the Community Boat Club marched out of the West End until they reached the State House, dropping off a boat called the Eugene C. Hultman inside the Hall of Flags. In 1939, the Community Boat Club petitioned the recently-elected Governor Leverett Saltonstall, who attended the Community Boat Club’s “christening ceremony” for one of their three-masted boats named after him in the summer of 1939. Saltonstall was convinced by the Club’s stated need for a boathouse, and he asked the state legislature in 1940 to officially designate part of Helen Storrow’s gift for completing the boathouse.

Community Boating, Inc. (CBI) was officially incorporated in 1946, although Lee was no longer part of the organization’s board at that time. Once Saltonstall delegated control of the new boathouse to the MDC, Hultman led the creation of a new Community Sailing Association that displaced the original Community Boating Club yet needed to rent the club’s original fleet. Lee resigned from the advisory board of the Community Sailing Association after disagreeing with changes introduced by a new supervisor, Jack Wood from MIT. Wood, in order to “start with boys of the right type” in his words, altered the sailing season to match the college calendar and closed up the boathouse’s workshop for boat building. In 1950, CBI acquired the rights to the boathouse originally leased from the MDC, and Lee eventually returned to the board of an organization expressly committed to “Sailing for All.” Lee continued to work as an advocate for improved public education, but he also spoke out against urban renewal of the West End, which razed over 40 acres of the neighborhood in 1958. Lee expressed his anger with the devastation in an ironic take on the “Sermon on the Mount”: “Blasted be the poor, for theirs is the kingdom of nothing, blasted be that they mourn, for they shall be discomforted. Blasted be the meek, for they shall be kicked off the earth.”

Community Boating, which had its 75th sailing season in 2021, is committed to providing equal opportunities for sailing on the Charles River regardless of ability or income. Because CBI is a non-profit, the organization can provide sliding-scale memberships for as little as $1/year, and sailing lessons at no charge to members. Since 2007, Community Boating’s Universal Access Program has incorporated “adaptive sailing” technologies for differently abled people to enjoy the water. Lee’s legacy has been remembered by CBI, and the many generations that have enjoyed sailing on Charles River, because of the collective action for recreation that he inspired.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Magazine; Boston Globe; Community Boating, Inc.; Mari Anne Snow, Gary C. du Moulin, and Charles Zechel, “Sailing for All: Joe Lee and America’s First Public Community Sailing Program,” Sea History no. 130, Spring 2010; Anthony M. Sammarco and Community Boating, Inc., Images of America: Community Boating, Inc. (Arcadia, 2018), Google Books; West End Museum