Joseph Rosen: The Engrosser of Harvard

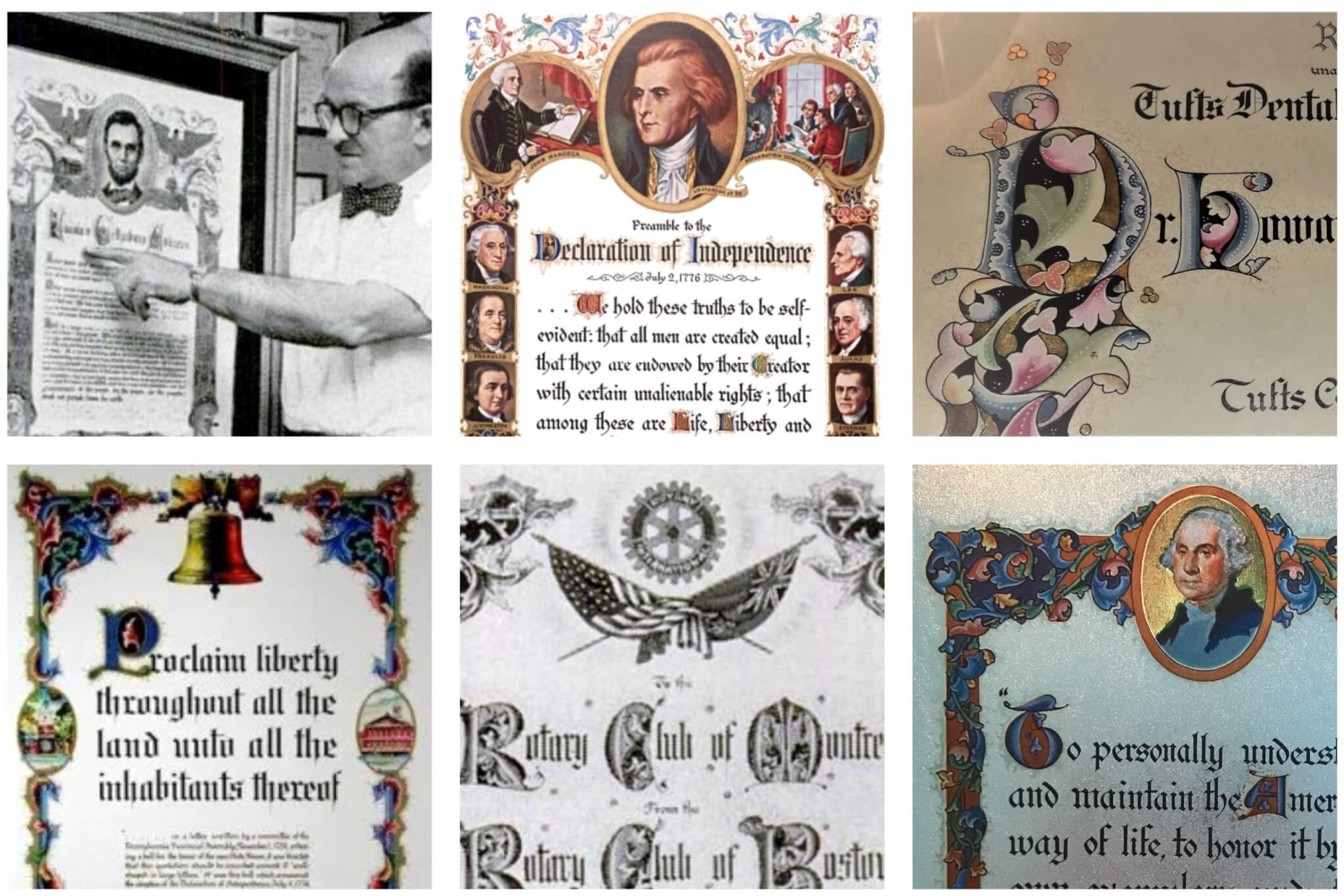

Inspired by his experiences at the West End House and HechtHouse, Joseph Rosen became one of the country’s leading engrossers, thanks in part to the kindness of James Jackson Storrow. He inscribed over 125,000 diplomas during his career, mainly for Harvard graduates, but he also produced honorary degrees for dignitaries such as the Roosevelt’s, Kennedy’s, and Winston Churchill. Despite his success, he never forgot the opportunities he received in the West End and found ways later in life to honor the West End House and its great benefactor.

Joseph Robert Rosen was born into a Jewish household near Minsk, Russia on May 28th, 1896. When he was only two-years old he emigrated to the United States with his parents, Isaac and Ryna, and several siblings. The family eventually settled in Boston where Joseph’s father worked as a tailor and seller of women’s clothes, while his mother cared for the household. The Rosen’s lived in several parts of the city, but according to Joseph, his experiences at West End settlement houses were essential in the formative years of his life.

Joseph played baseball at the Hecht House, and throughout his life he fancied himself a

“frustrated shortstop,” even though he was talented enough to participate in some professional tryouts. He was also considered a basketball star at the West End House, which was where he first caught the attention of James J. Storrow; Boston entrepreneur, politician, and the chief benefactor of the West End House. Like many West End boys, Joseph benefited from the West End House’s dedication “to the moral, physical and mental development of the youth of Boston.” Besides playing sports there, he made many life-long connections and in his later years he repaid his debt to the West End House by serving as a member of its board and of the executive committee for its 30th anniversary celebration.

Joseph attended the Boston High School of Commerce where he was first exposed to the art of engrossing, the embellishment of documents using calligraphy or illustrations. His plan after graduation was to further study engrossing at the Zanerian College of Penmanship, and he had assistance fulfilling that dream from none other than Storrow himself, who gave Joseph $30 for his train fare to the Midwest. Joseph would later repay the favor by spearheading efforts to name the Charles River embankment after Storrow upon his death in 1939. After studying at Zanerian College from 1914 to 1915, he lingered in the Midwest, studying at the Chicago Art Institute and serving as an apprentice for the Kassel Engrossing Company.

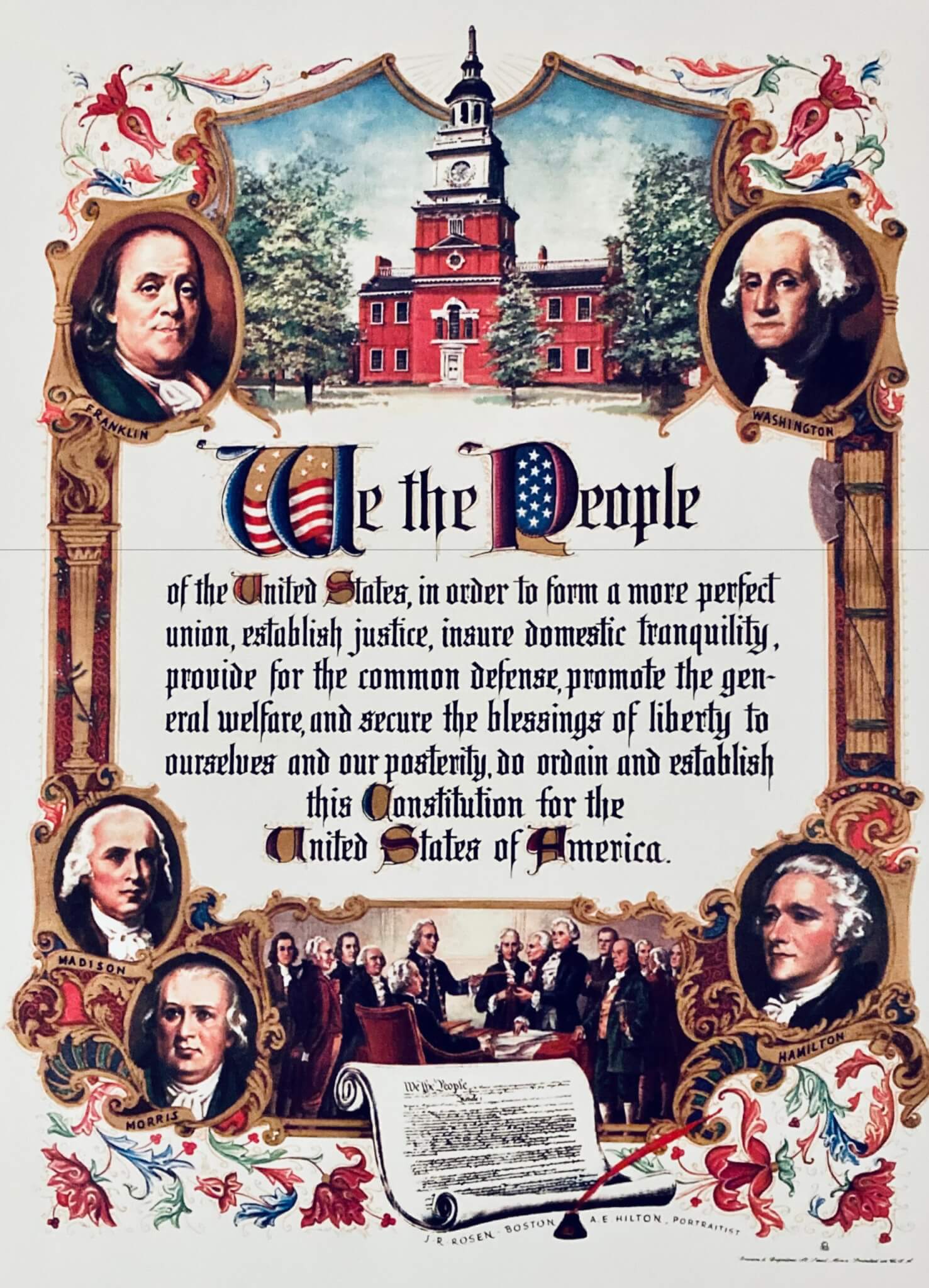

Upon returning to Boston, Joseph was offered a job as Harvard University’s temporary engrosser by its president, A. Lawrence Lowell, who had seen and admired Joseph’s work. During this same period Joseph met Gertrude Burnce whom he married on July 19, 1918, and he also served in the United States Naval Reserve during World War I. Eventually he set up business in an office in the Little Building at 80 Boylston Street in Boston. Over the years his business grew to the point where he was considered one the top 50 engrossers in the country. Besides becoming the permanent engrosser for all of Harvard’s graduation diplomas, personally inscribing each candidate’s name by hand, Joseph acquired contracts with the City of Boston, Northeastern University, and created work for numerous other schools and organizations, such as the Shriners and Freemasons, across the country.

Throughout his career, Joseph attracted the attention of Boston Globe writers who featured him in numerous articles. One report noted that he wrote hand-lettered honorary degrees for “Albert Einstein, King Albert of Belgium, Gen. George C. Marshall—for the commencement when the Marshall Plan was announced—the Roosevelts and John Fitzgerald Kennedy.” He became friendly with Franklin Roosevelt Jr. and was once invited by him to visit at Washington D.C. Another story recounts a secret project during WWII involving Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Churchill flew covertly to the United States in 1943 to receive an honorary degree from Harvard, and all involved, including Joseph, had to be sworn to secrecy by Federal agents.

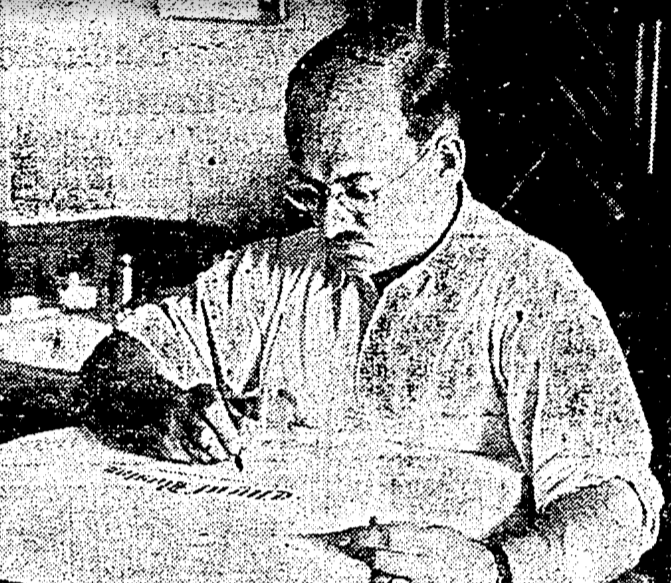

Joseph’s skills included ornamental penmanship, calligraphy, engraving, illuminating, lithography, framing, gold raising, as well as working with specialty forms and mediums, such as talio-chrome and foil-etching technique. His work was described as “the fanciful and delicate works turned out by medieval monks…[using] a hair-thin line and many colors, often gold.” He was said to have worked twenty hours a day in his prime, arriving at the office at 4:00 a.m. and working until midnight. When he was 66, a Globe reporter asked him about retirement and Joseph answered “Don’t be ridiculous. I love my work, and the people associated with it. Sure, I like fishing when I get the chance. But who wants to fish 365 days a year?”

Joseph and Gertrude had two daughters, Enid and Marcia. The family lived Roxbury, Dorchester, and finally settled in Brookline. When work allowed, Joseph loved spending time with his grandchildren, often playing pass football with them on Saturday afternoon as reported by his grandson Dana Jackson (Ira’s son) and in the newspapers. Joseph lost Gertrude in 1963, and he himself passed away on June 17, 1965 at the age of 69, ironically on the same day as Harvard’s commencement that year. Joseph’s business, J.R. Rosen Studio was purchased twice after his passing. Today, Bob Goodwin, who purchased the firm in 1977, continues to produce quality engrossing work in the tradition of Joseph Rosen from the J.R. Rosen Studio at 350 Copeland Street, Quincy.

Article by Alex Maher and Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: https://www.jrrosenstudio.com/; https://www.ancestry.com/; https://www.wickedlocal.com/story/archive/2015/08/15/calligraphy-is-in-his-blood/33677164007/;Boston Globe: October 6, 1936; December 1, 1937; April 13, 1944; June 4, 1957; April 27, 1961; November 11, 1962; October 25, 1964; June 18, 1965