Revisiting Joseph Caruso’s 'The Priest' & the West End’s Sicilian Immigrant Community

Joseph Caruso’s novel The Priest (1956) vividly captures daily life for the West End’s Italian immigrant population in the mid-twentieth century, drawing on actual events, historical landmarks, cultural rituals, and economic challenges which shaped the West End community for generations.

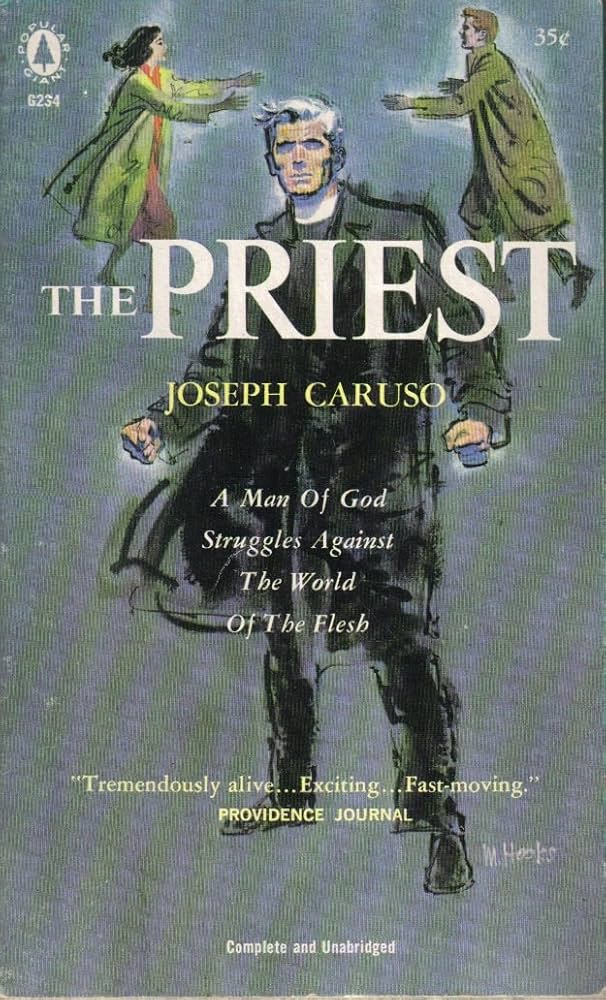

Joseph Caruso’s critically-acclaimed novel The Priest is a long-forgotten literary homage to the vibrant and tight-knit West End neighborhood of the early to mid-20th century. Published in 1956, The Priest follows Father Octavio Scarpi, a curate with a troubled past, who seeks redemption and purpose through serving his community. After witnessing a shocking deathbed confessional, he engages in a desperate attempt at proving the innocence of an alleged murderer and fellow West Ender awaiting the death penalty. Beyond its ostensibly potboiler plot, The Priest offers a rare and nuanced portrait of the West End’s immigrant enclave from Sicily.

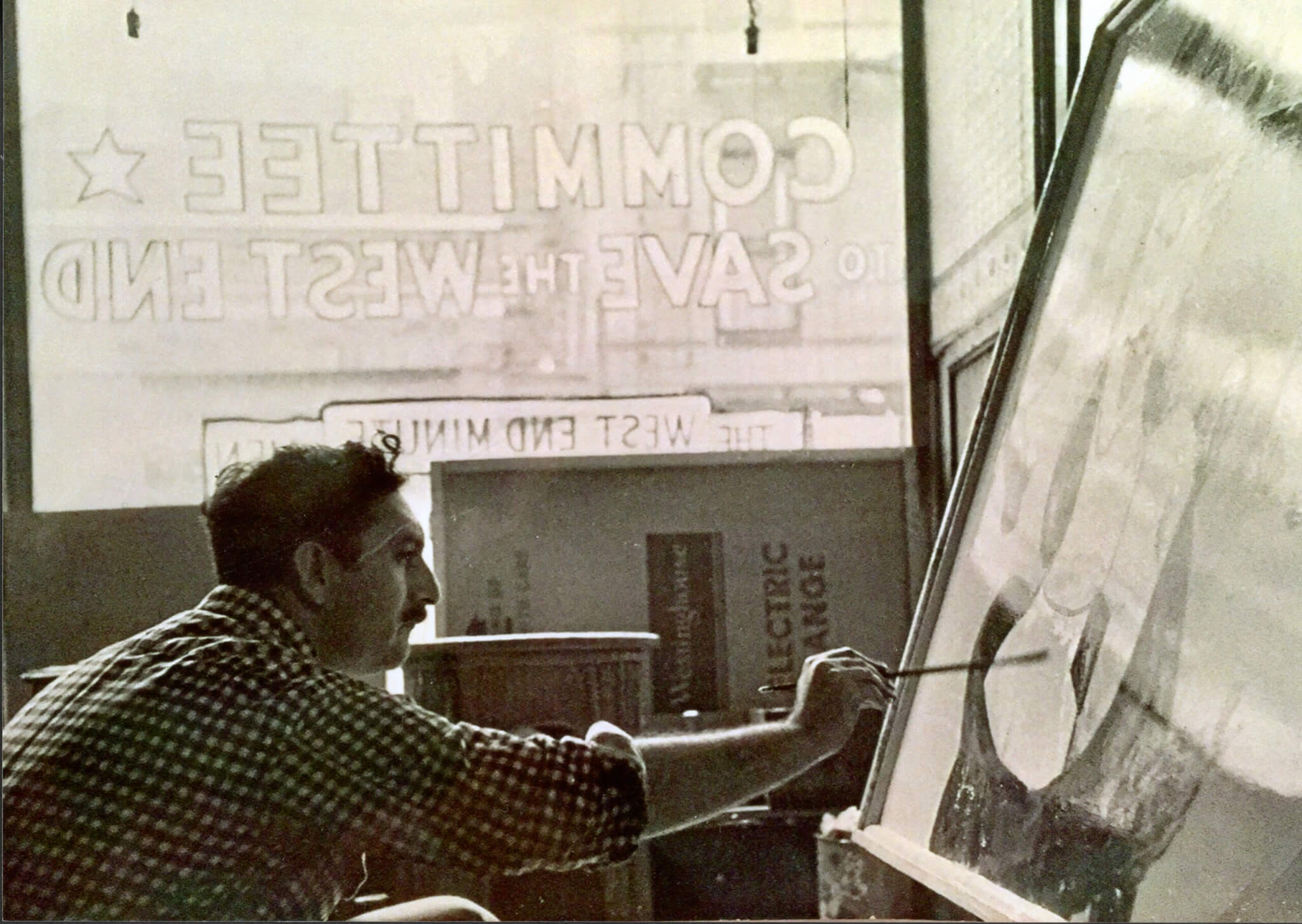

The novel’s author, Sicilian-born Joseph Caruso, was a notable figure in the community. Born in 1924, he immigrated during the 1930s with his family to the West End, where he attended the Blackstone School and later studied painting through the Museum of Fine Arts on scholarship. After several years spent traveling through the American West and serving in World War II, Caruso returned home to the West End. While raising a family on Green Street and working for the U.S. Postal Service, he authored several bestselling novels; penned book reviews for the Boston Globe; co-founded an art gallery through the Hollis Street Art Guild in the South End; and established Doric Productions, an independent film company. Later, Caruso became a founding member of The Committee to Save the West End. He also contributed to Dr. Erich Lindemann’s landmark study on the mental health consequences of displacement and forced urban relocation.

By the mid-1950s, Italians would constitute about 42 percent of the West End’s population, according to research conducted by The Center for Community Studies. The Priest dramatizes both this period and the 1930s-era of Father Scarpi’s youth, growing up on Hale Street where many of its residents hailed from cities along the eastern Sicilian coast, such as Augusta. This population would dominate the area between Green and South Margin Streets with Pitts, Hale, and Norman Streets running between them. Much of The Priest’s vivid descriptions and plot points are inspired by actual events, historical landmarks, cultural rituals, and economic challenges which shaped West End life for generations.

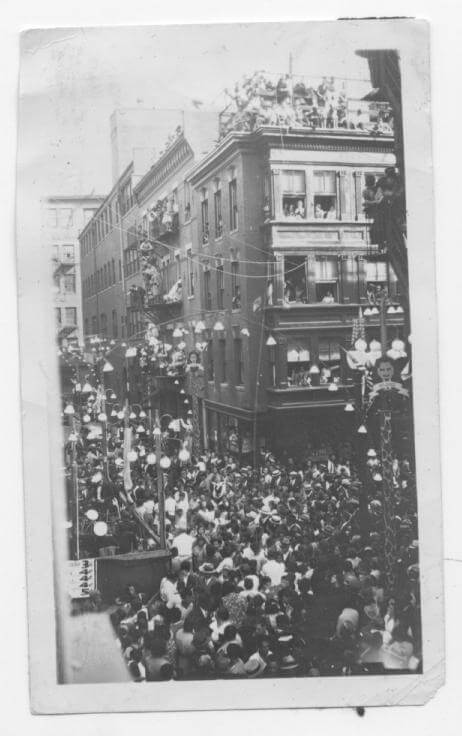

Father Scarpi’s memories, interspersed throughout the book’s narrative, reveal a boyhood dominated by tradition, family, and poverty. His recollections of the Feast of St. Lucy’s, held annually over Labor Day Weekend, depict a major festival in the West End. From South Margin to Hale Streets, the neighborhood would be decorated in strands of multi-colored string lights with a colorful wooden bandstand situated before the Alles & Fisher’s J. A. Cigar factory on South Margin Street. Thousands of spectators would attend the parade, observing its procession and live music. They would gather from both around the West End and across Boston, including nearby Medford and Somerville, where some former West Enders had migrated for suburban life. For Father Scarpi, Feast Day would also be a family affair, as “his mother would fling the windows open and he and his brothers would look out, waiting for the parade to turn the corner at Green Street.” A procession fronted by “little girls with their papier-mâché wings” would proceed groups of local fishermen from both the North and West Ends, with Scarpi’s father among them, who shouldered a life-size statue of the Madonna. Neighbors would hurl dollar bills from their windows to be collected by procession organizers and pinned to ribbons around the statue’s neck.

The “Greasy Pole” contest, occurring at the end of nearby Hale Street, would follow the parade. Accompanied by a brass band, residents would plant a 30 to 40-foot vertical pole in a deep hole between the cobblestones. Buttressed at the ground level, the pole would then be secured by fishing cables to neighboring rooftops and coated in thick axle grease. A hoop dangling a prize of meats, breads, fish, and cheese would be attached to the top of the pole by rope and pulley. Accompanied by a brass band providing musical effects, each contestant would attempt to “skin the pole,” and reach the prize at the top before most inevitably slid back down to the bottom. Father Scarpi recalls these details in vivid recollection, associating the tradition with a haunting memory of his brother Nick, later killed in action during World War II, who wins the contest one year to the pride of his family and community.

The Priest also explores the working-life realities that defined the West End, particularly among its pushcart peddlers and deep-sea fishermen. Lasting well into the 1940s, the peddlers’ market drew vendors selling fruit and produce from pushcarts and horse-drawn wagons along Blackstone and Cross Streets (meeting at Haymarket Square) on Saturdays, from dawn till dusk, weather permitting. Father Scarpi would recall how “the peddlers, arranging the wares on their carts, would sing C’e ‘na Luna Menzo Mare as they prepared for market.” Livery stables, located throughout the West End, would offer vendors the opportunity to rent a horse and carriage before loading their wagon with produce at the Terminal and Commonwealth Pier before taking it to market. The buildings of certain liveries, such as the JJ Walker Stable on North Russell Street, would remain standing until the West End’s demolition in 1958.

As a ten-year-old boy, Father Scarpi would assist peddlers at Quincy Market and the Custom House Tower, where he’d “work for ten or fourteen hours, running errands and shrilling the peddler’s wares, his voice becoming hoarser and fainter as the day wore on.” By age fourteen, he’d devote summer vacations to helping his father at sea, working eighteen hours straight hauling in the day’s catch, before gutting and cleaning loads of haddock.

Father Scarpi’s recollections throughout The Priest also reveal the instability of work and its consequences. Growing up, he “could remember the immigrants filing into the cigar factory at the corner of Hale Street” until its abrupt closing in the late 1930s. Before then, H. Traiser & Co. Cigars, who produced the popular Harvard and Pippins brand during that time, would also be involved in the contentious 1919 Boston Cigar strike. An estimated 2,100 of the city’s 2,400 cigar makers would walk off the job in protest over low wages. This would lead to the relocation of certain factories to other states and the use of machines over human labor. Although H. Traiser & Co. Cigars would resume production later that same year, their eventual closing by 1938 would result in job losses for many throughout the neighborhood, including Father Scarpi’s brother, Nunzio, a foreman whose unemployment would lead to a tragic accident, leaving him paralyzed.

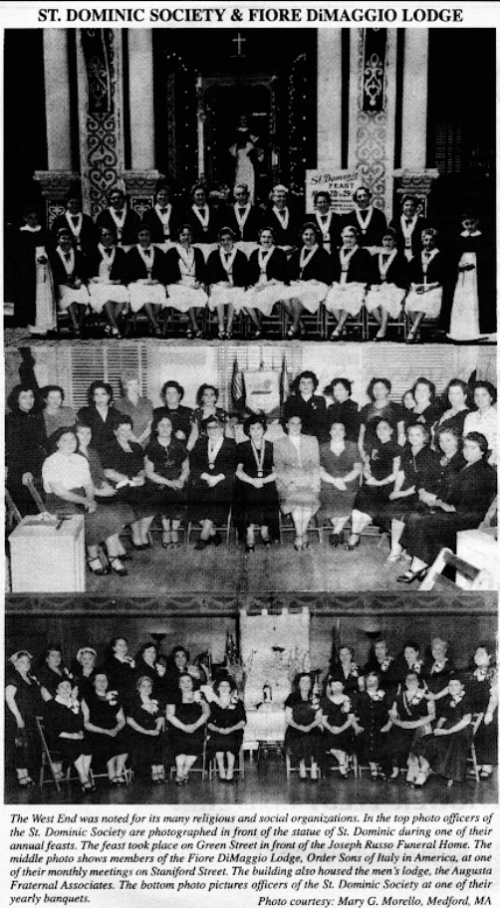

Themes of class and poverty run concurrent with those of community and resilience. Father Scarpi is frequently entangled in humorous and light-hearted tensions within his parish and an organization based on the Augusta Fraternal Associates and Saint Dominic Society, which sponsored cultural events and the Saint Dominic Feast throughout the West End into the 1960s. Organizations and festivals such as these helped West Enders preserve their identities long after the forced displacement from their community. Throughout The Priest, several subplots arise between Father Scarpi and members of the St. Dominic’s Fraternity that dramatize a wide variety of political and social tensions within the immigrant enclave. These include the long-reaching trauma of an abusive feudal system in Italy; to regional differences among Sicilians; to generational challenges of their families’ Americanization and issues of gender inequality among its members as “the men had always seen to it that the women were numerically, if not vocally, in the minority.” Despite these tensions, the community works in tandem to preserve traditions at the heart of those Sicilian Americans who call the West End home. By the novel’s end, it is this same community which restores Father Scarpi’s own faith in himself, renewing his sense of purpose through serving others.

Article by Olivia Kate Cerrone, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Santo J. Aurelio, “Land of Hope, Land of Tears: Jewish and Italian Immigrants in Boston, 1880 to 1914,” Thesis, Harvard University, 1985; Santo J. Aurelio, “West End Memories,” The West Ender, Vol. 17, No. 1, 2001; The Boston Daily Globe, “2000 Cigarmakers Strike in Boston,” July 8, 1919; The Boston Daily Globe, “Waitt & Bond, Inc, to Leave Boston,” August 14, 1919; J.J.P., “La Festa,” The West Ender, Vol. 2, No. 3, 1986; Joseph Caruso, The Priest (New York: Macmillan, 1956); Salvatore Ferraguto, “The Feast of the Madonna,” The West Ender, Vol. 12, No. 2, 1996; Salvatore Ferraguto, “The Peddler’s Market,” The West Ender, Vol. 11, No. 1, 1995; Herbert Gans, The Urban Villagers: Group and Class in the Life of Italian-Americans (New York: The Free Press, 1969); Joseph Morello, “A West End Romance That Lasts for Decades,” The West End Museum; The West End Museum, “A Stroll Down Spring Street.”