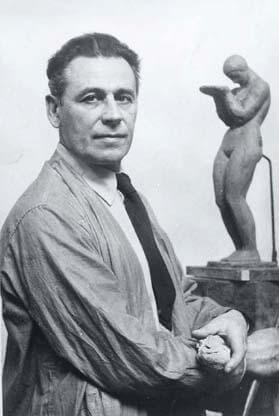

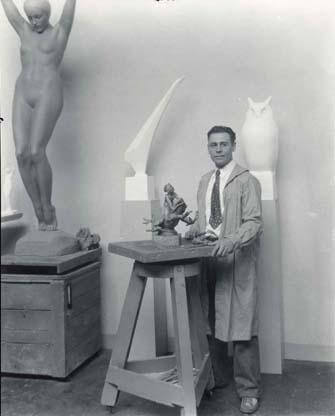

Richard H. Recchia

Richard H. Recchia, an Italian-American sculptor, achieved early artistic success growing up in the West End before achieving fame at major exhibitions.

On November 20, 1885, Richard H. Recchia was the oldest of five children born to Frank and Rosa Louisa Recchia in Quincy, MA. His parents immigrated to Massachusetts from Italy, and his father, Frank, was a marble sculptor. The Recchias lived on Myrtle Street in the West End during Richard’s teenage years, when he followed in his father’s footsteps as a sculptor. Between 1904 and 1907, Recchia took classes at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts, and excelled under the guidance of Bela Lyon Pratt. Pratt directed the school’s Sculpture Department, and he was one of Recchia’s two mentors; the other was Daniel Chester French, the preeminent American sculptor of memorial busts in the early twentieth century. In 1907, Recchia, at the age of 22 (incorrectly listed as 19 in the press), displayed his sculpture called “The Athlete” at the Copley Society’s art exhibition. Recchia received strong praise from A.J. Philpott, the art editor for the Boston Globe, for his originality and attention to detail:

It was distinctive–it was Recchia’s work. It had a personality of its own. And somehow this boy early caught that subtlest thing in sculpture, the power to give flesh a living quality, not a mere dead copy of what purported to be flesh. He gave it the nervous quality of life.

Philpott told one story, from Recchia’s mother, about the young sculptor waking up in the middle of the night to work on his design of “The Christ of the Cross Looking Down on the Troubled World.” Rosa Louisa remarked that “Richard’s brothers thought he was crazy that night.” Philpott also reflected upon whether Richard’s dedication and artistic genius could be attributed to the “rich Italian artistic blood” he inherited from his father Frank. But he concluded that artistic talent was usually not inherited: many famous artists, such as Rembrandt or Diego Velásquez, came from parents who were not artists, and those artists’ children did not replicate their skills. This did not discredit Recchia, but rather did the opposite: for Phillpott, his readers ought to have “let him stand in the same category with the sons of peasants, millers, barbers and lawyers–stand on his own inherent merits as an artist, fortunate that he was born with such a satisfactory environment.” In the Globe’s profile of Recchia, he is first described as a “young Boston sculptor,” and next as a “West End boy.”

Recchia eventually planned to leave the West End to study sculpture in Europe. Living in Paris in 1915, married Ana Diaz, a Chilean woman, and had two children before Diaz died in 1926. Recchia then moved to Rockport, MA, and married his second wife, Kitty Parsons. Recchia’s sculpture called “Fantasy” received one of two honorable mentions in the sculpture category at the Boston Tercentenary Fine Arts and Crafts Exhibition at Horticultural Hall in July 1930. The various tercentenary celebrations, including the art exhibition, commemorated the 300th anniversary of the founding of Boston in 1630. A.J. Philpott, the secretary of the Tercentenary Art Committee, observed that the July exhibition, one of multiple tercentenary art displays that year, was “the most comprehensive of its kind ever held in the City of Boston.” Recchia displayed “Fantasy” once again in 1940, at the Whitney Museum of American Art’s National Sculpture Society Exhibition in New York City. Aside from sculptures, Recchia also designed medals, such as “Aspiration and Inspiration” in 1944, a medal with a boy leaping and the words, “Too Low They Build Who Build Beneath The Stars.”

Recchia died in Rockport, MA in 1983, and carved his own headstone prior to his death. He is mostly remembered as a distinguished sculptor from Quincy or Rockport, but Recchia’s time as a “West End boy” was formative in his path to artistic achievement.

Article by Adam Tomasi

Source: Boston Globe (“Young Boston Sculptor,” September 22, 1907, ProQuest); Smithsonian American Art Museum; Medallic Art Collector; The Met; Jamaica Plain Historical Society (for Bela Lyon Pratt); Tercentenary program; Whitney Museum