Rid of the Grid: The Destructive Legacy of Superblocks in Urban Renewal

In the 20th century, the superblock concept emerged from modernist planning principles as an alternative to the traditional grid. These superblocks, while theoretically promising a more ordered and healthy urban environment, proved destructive when implemented through America’s urban renewal programs, including in Boston’s West End.

In the middle decades of the 20th century, American cities underwent a dramatic transformation under the banner of urban renewal. One modernist planning concept—the superblock —became a powerful tool in this reshaping of urban America, often with devastating consequences for existing communities and the urban fabric. This planning approach, championed by influential architects like Le Corbusier and embraced by city planners nationwide, fundamentally altered the character of American cities while displacing hundreds of thousands of residents, particularly from minority and working-class neighborhoods.

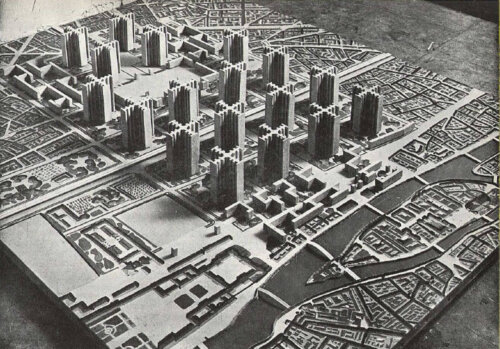

The superblock concept emerged from modernist planning principles that rejected the traditional urban grid in favor of large, consolidated blocks that eliminated many streets and consolidated land into massive parcels. On these blocks, tall, isolated buildings surrounded by open space were built, representing a complete departure from the traditional pattern of streets lined with mixed-use buildings. Le Corbusier, the architect most associated with superblocks, envisioned them as long swathes of pavement, with skyscrapers placed in parks, the streets surrounded by arterials to allow cars to move faster, and commerce and housing entirely separated. These ideas, while theoretically promising a more ordered and healthy urban environment, proved destructive when implemented through America’s urban renewal programs.

Traditional street grids typically featured walkable blocks ranging from 200 to 400 feet in length, creating a dense network of intersections and multiple paths between any two points. This pattern emerged organically in many cities and was formalized in plans like New York’s 1811 Commissioners’ Plan, which established Manhattan’s famous grid. The traditional grid offered several key advantages:

- Permeability: The frequent intersections created multiple routing options for pedestrians and vehicles, distributing traffic flow and creating redundancy in the network.

- Economic Opportunity: Small blocks created more corner lots and street frontage, maximizing opportunities for retail and commercial activity.

- Adaptability: The regular pattern of small parcels allowed for incremental development and redevelopment over time, enabling cities to evolve organically.

- Human Scale: Block sizes were naturally limited by comfortable walking distances and the economics of land subdivision.

By the mid-19th century, however, the grid was considered old-fashioned, an eyesore, and even unhealthy. The American Institute of Architects, for instance, called gridded Philadelphia “an unyielding and ugly rectangular system” in a report. Many thought the densely built grid deprived residents of open space, sunlight, and air. These deprivations were primarily due to high land values and lot coverage, not the grid per se, but it is easy to see why “slum” conditions were blamed on the grid.

Superblocks, by contrast, typically spanned what would have been multiple traditional blocks, often measuring 1,000 feet or more on a side. This dramatic scaling up of urban form was justified by modernist planning principles that prioritized efficiency and rational organization over organic development. The implementation of superblocks fundamentally altered urban environments in several ways:

- Reduced Connectivity: By eliminating cross streets, superblocks forced pedestrians and vehicles to take longer routes around their perimeters, reducing the number of possible paths between destinations.

- Decreased Economic Activity: The elimination of street frontage and corner lots reduced opportunities for street-level retail and local employment options.

- Spatial Monopolies: The large scale of superblocks meant they were typically developed all at once by a single entity, eliminating the possibility of incremental, diverse development.

- Spatial Isolation: Superblocks and towers in the park created physical and psychological barriers between their residents and the surrounding city. The elimination of traditional street patterns and the creation of vast, often poorly maintained open spaces contributed to a sense of isolation and disconnection.

- Auto-Centric Design: The large scale of superblocks often prioritized automobile access over pedestrian movement, with wide arterial roads around their perimeters.

The contrast between these approaches is clearly illustrated in New York City. The traditional Manhattan grid north of 14th Street creates a fine-grained urban fabric that supports vibrant street life and diverse economic activity. By contrast, Stuyvesant Town, built in 1947, consolidated 18 traditional blocks into superblocks, eliminating seven east-west streets and four north-south streets. The development’s internal paths, while pleasant for residents, do not function as true public streets, and the project’s edges create significant barriers to movement through the neighborhood. Although Stuyvesant Town predates the federal urban renewal program, its design principles were highly influential in many early renewal projects.

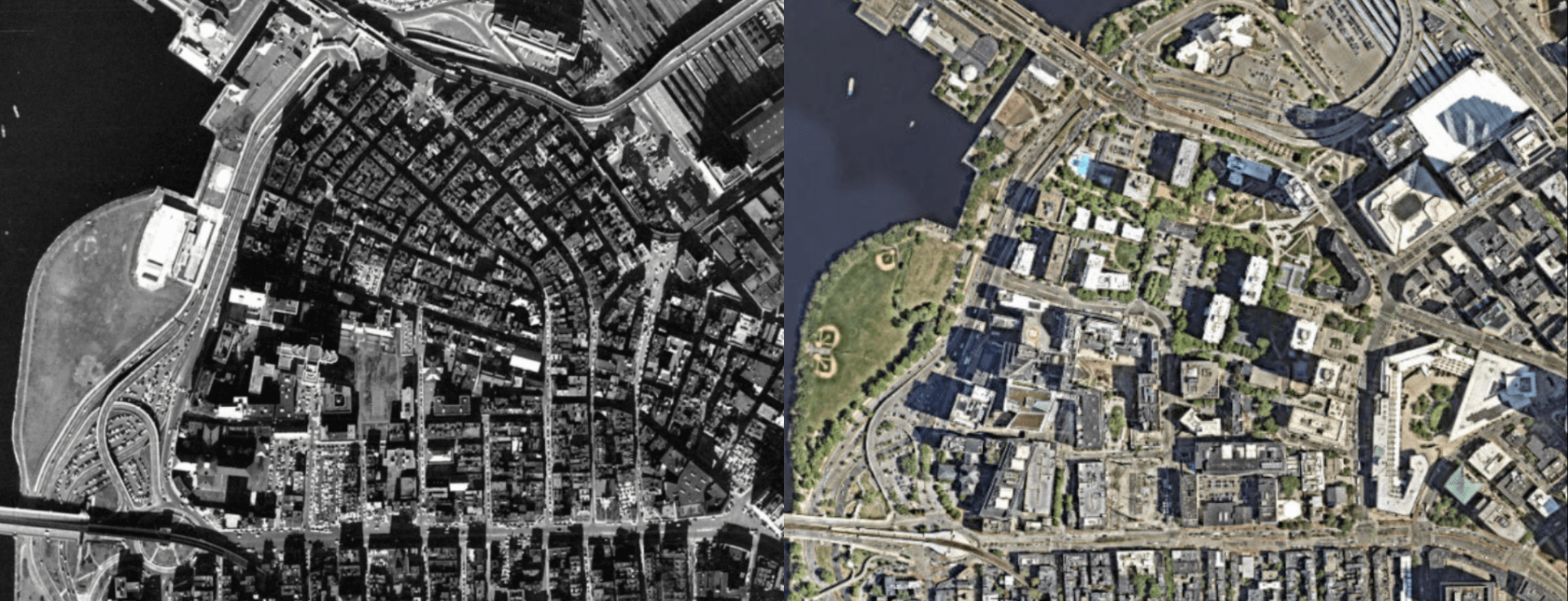

Urban renewal took the superblock concept and ran with it. In Boston, the West End’s traditional street grid was erased and replaced with superblocks containing the isolated towers of Charles River Park. The result was a dramatic reduction in connectivity: where once there were dozens of possible routes through the neighborhood, now there were only a few paths around the superblocks’ perimeters. In Chicago, the Robert Taylor Homes stretched for two miles along the State Street corridor, creating a massive superblock of public housing that effectively segregated its residents from the surrounding city. Other New York City projects, such as Lincoln Center and the former World Trade Center, used not only the superblock design but also elevated the block to create a wall-like and exclusionary presence.

Perhaps no project better exemplifies the destructive impact of these planning concepts than Pruitt-Igoe in St. Louis. Completed in 1954, this massive public housing project consisted of 33 eleven-story buildings arranged in a superblock pattern, surrounded by expanses of poorly defined open space. The project replaced a low-rise, mixed-income neighborhood with an isolated complex that quickly became a symbol of urban renewal’s failures. Its spectacular demolition in 1972 came to represent the death of modernist urban planning principles.

The failure of these planning approaches became increasingly apparent by the 1970s. Jane Jacobs’s influential 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities had already articulated a devastating critique of modernist planning principles, arguing for the importance of traditional street patterns, mixed uses, and organic urban development. Today, many cities are recognizing the value of traditional street grids and seeking ways to break down superblocks into more manageable urban forms: Portland, Oregon has actively worked to restore street connections through superblocks; New York City’s Greenwich and Fulton Streets now run through the reconstructed World Trade Center site; and other cities are implementing “tactical urbanism” approaches to create more permeable urban environments.

The lessons learned from this period of urban transformation continue to influence contemporary planning. The failure of superblocks has led to a renewed appreciation for the traditional street grid’s ability to support diverse, adaptable, and resilient urban environments. As cities face new challenges in the 21st century, the traditional street grid’s capacity to accommodate change while maintaining human scale and connectivity offers valuable lessons for future urban development.

Article by Daniel Spiess, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Governing, “Blocks, Superblocks and the Making of Cities”; Museum of the City of New York, “The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-Now: 1811 Plan”; Museum of the City of New York, “The Greatest Grid: The Master Plan of Manhattan, 1811-Now: Housing Superblocks”; Planetizen, “What Are Le Corbusier’s Towers in the Park?”; Strongtowns, “The 4 Rules of Fostering Good Urbanism, According to Jane Jacobs.”