Scollay Square

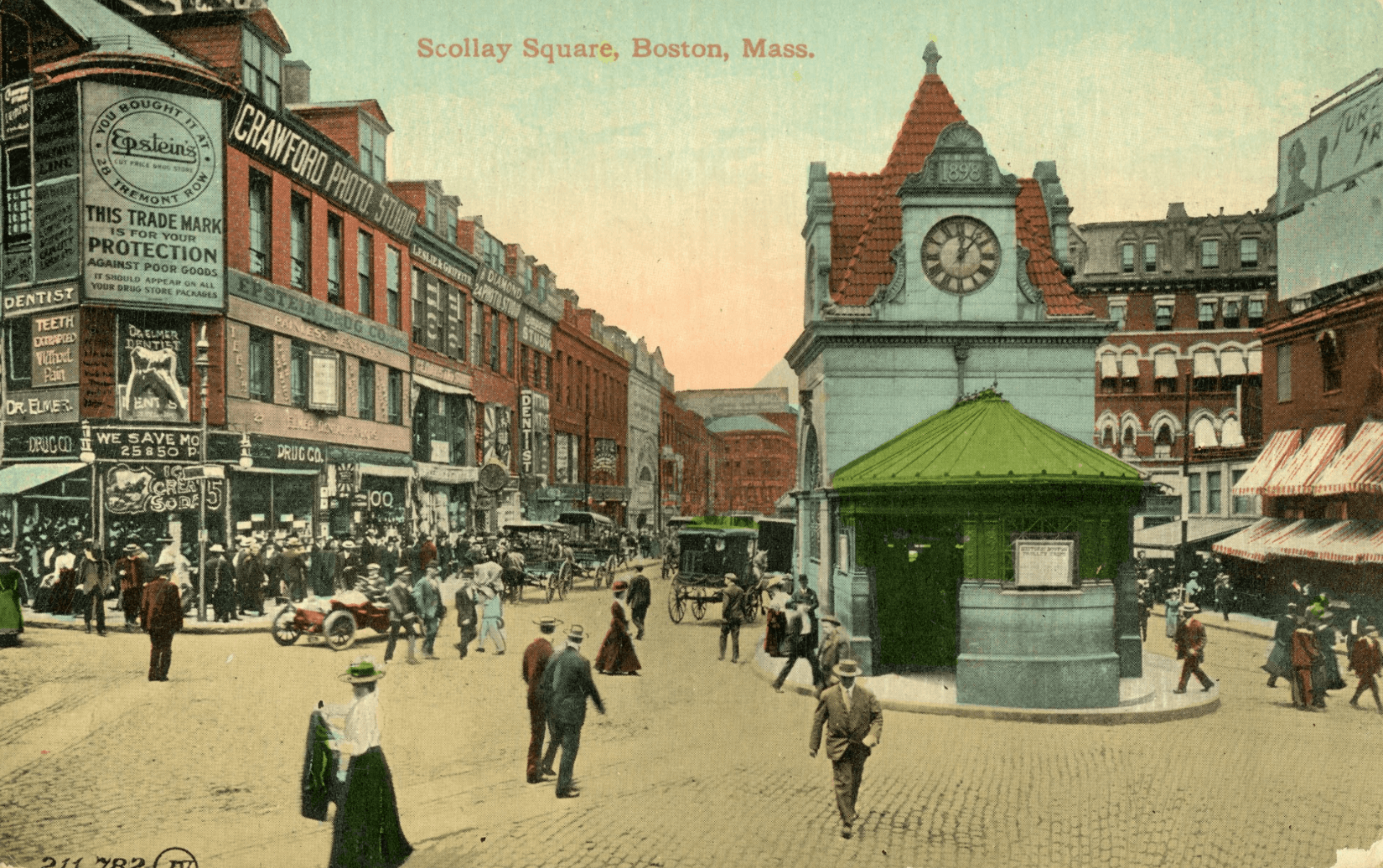

Scollay Square was a vibrant entertainment hub in Boston from the mid-19th century to the early 1960s, known for its burlesque theaters, comedy shows, boisterous bars, and eclectic mix of businesses. Located directly next to the West End at the intersection of Cambridge, Court, and Tremont streets, it attracted both locals and out-of-town visitors, including sailors, with its lively nightlife and commercial offerings. The area was demolished in 1962 as part of an urban renewal project, to be replaced by Government Center.

From the mid-19th century until the decade following World War II, Scollay Square was the entertainment capital of Boston. Burlesque theaters were the main attraction, but this quarter mile block at the intersection of Cambridge, Court, and Tremont streets also featured comedy performances, variety shows, movie theaters, a legendary hot dog stand, tattoo parlors, penny arcades, and pawn shops, with countless restaurants, bars, and hotels. Bordering the West End from the south, Scollay Square was Boston’s debauchery district, frequented by both the Brahmin elite and working classes, and was a particular draw for out-of-town sailors seeking a memorable night during off-duty periods.

Its contemporary legacy is intertwined with Boston’s controversial urban renewal initiatives. Aside from a few commemorative plaques, all vestiges of Scollay Square were razed in the early 1960s to construct the new City Hall, Center Plaza, and the JFK Federal building—the area known as Government Center. One former West Ender, who moved from Boston and returned after Scollay Square was demolished, remarked: “To try and even imagine the way it looked compared to the way it is now was very difficult. It’s hard to believe it ever really existed.”

Years before the salacious burlesque shows, Scollay Square had a posh character. Starting in the 1830s, it was an upper class residential destination that resembled Beacon Hill, then it became a commercial district with boutique shops and high end restaurants. Several law offices made nearby Pemberton Square their home, which also served as the longtime headquarters for the Boston Police Department. From the era of stagecoaches through the advent of streetcars, the area was an important transportation checkpoint, and the “Scollay” name emanated from the four-story Scollay Building built in 1795, where chariot drivers would stop in front of when dropping off and picking up passengers.

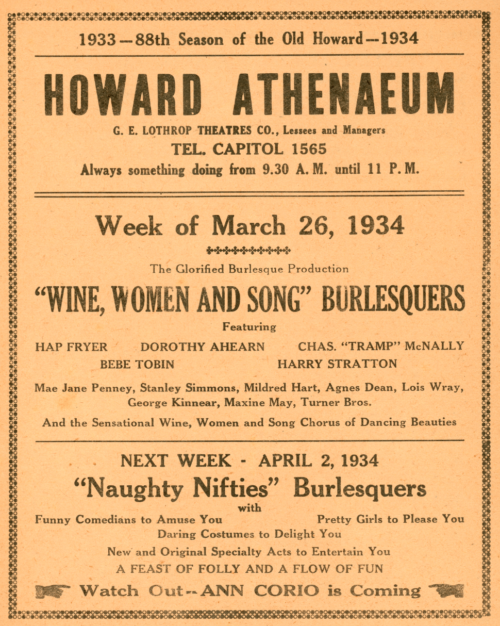

The transition to entertainment at the turn of the 20th century was accelerated by the presence of the Old Howard Theater, Scollay Square’s premier attraction. Launched in 1845 as the Howard Athenaeum, the then-segregated theater initially showcased Shakespearean drama and Italian opera, but as the ethnic makeup of the West End evolved, it pivoted to popular entertainment, with vaudeville, slapstick comedy, circus performers, boxing matches, and pantomime. By the 1920s, it became a burlesque mainstay, with Ann Corio enchanting audiences with her playfully suggestive striptease act. The nearby theaters began exclusively booking burlesque performers like Rose de la Rose, Georgia Sothern, and Sally Rand, each of whom crafted original risqué stage personas.

Some of the most famous comedians of the 20th century also performed at the Old Howard, including Milton Berle, Abbot & Costello, Fred Allen, and the Marx Brothers. Because it flouted Boston’s puritanical sensibilities, it was the frequent target of censorship from the Boston Watch & Ward Society, the city’s unofficial morality patrol. Though burlesque was sexually tame compared to today’s standards, high society folks attacked it as lewd and indecent. Nonetheless, the Old Howard attracted men from the upper classes, as future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes and future President John F. Kennedy were known to frequent the theater, and it had a section exclusively for Harvard professors.

Other theaters attempted to compete with the Old Howard. The Crawford House was a refurbished hotel which shifted to burlesque during 1920s prohibition, and its main draw was Sally Keith, whose stage act involved affixing tassels to different parts of her body and defying the laws of human physiology. The Star Theater, later known as the Rialto, was flippantly known as the “scratch house” because of its vermin-infested seats. The Olympia Theater originally booked vaudeville shows before exclusively switching to movies, and the Theater Communique was the first in Boston to show a motion picture in 1906. Local talent had opportunities to perform at theaters like the Bowdoin, Palace, and Beacon.

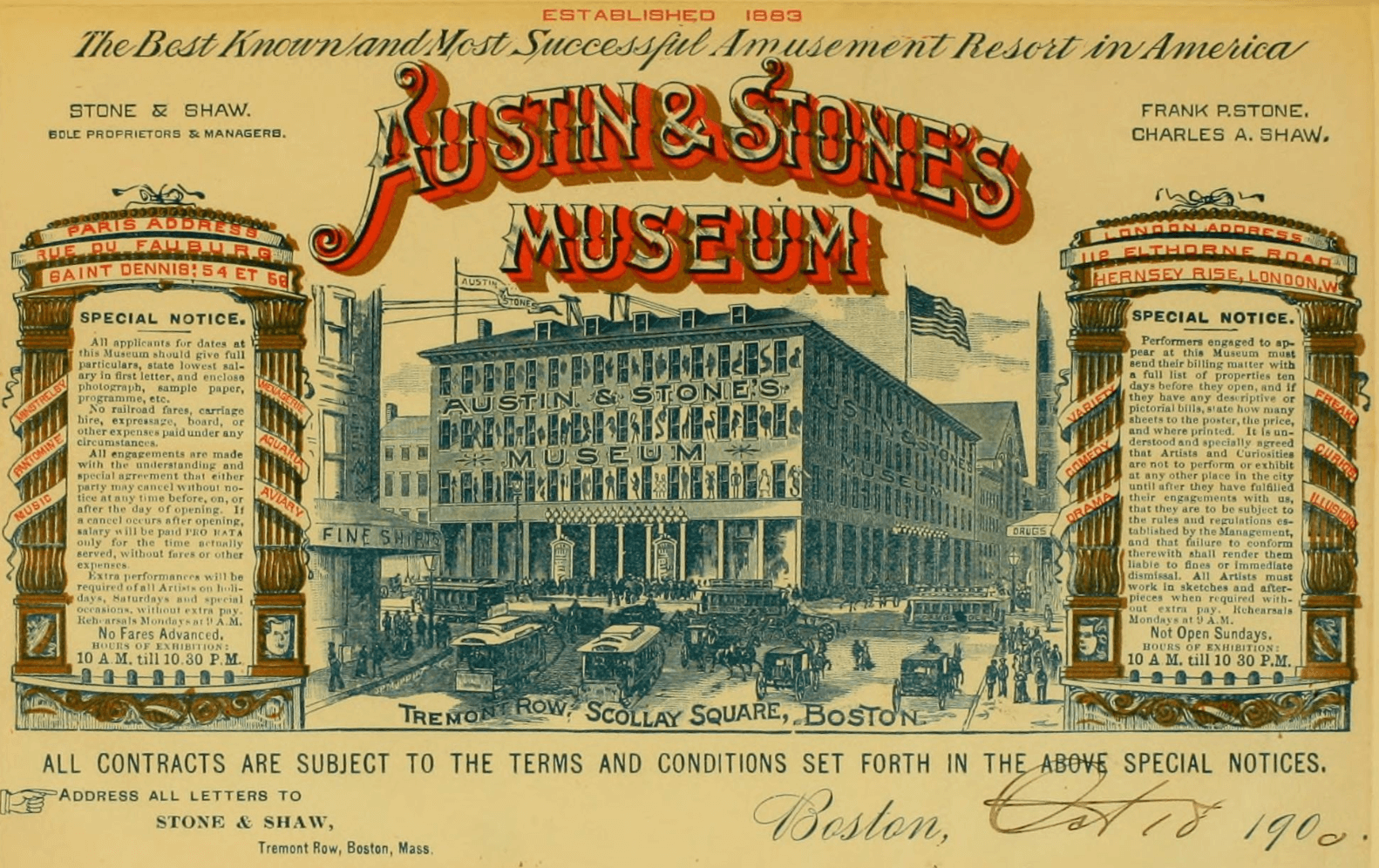

Aside from the theaters, Scollay Square featured quirky establishments like Jack’s Joke Shop, Austin & Stone’s Dime Museum, and the Amusement Centre penny arcade. Patten’s, Carnival Cafe, and Crescent Grill were popular restaurants, while Half Dollar, Jack’s Lighthouse, and Marty’s were a few of the many taverns that people flocked to after shows. Burlesque’s provocative sensuality was geared toward men, but women regularly attended, as several photos from the era show men bringing their dates to the Scollay theaters, and the Old Howard even hosted a lady’s night. It also had a number of bars frequented by Boston’s LGBTQ+ community. Beyond Bostonians, Scollay Square served a specific out-of-town clientele: sailors.

From the 1898 Spanish-American War to the World War II years of the 1940s, Scollay Square was always a popular jaunt for off-duty sailors while their ships docked in Charlestown’s Navy Yard. They’d stay at the Hotel Imperial, known for its permissive policy towards prostitution, and the tattoo parlors stayed in business because of their popularity with sailors. The bestselling 1952 novel, Scollay Square by Pearl Schiff, centers on a young woman’s romance with a visiting sailor. And after raucous night out, it became a rite of passage to stop at the square’s most fabled hot dog stand.

Joe & Nemo’s was around the corner from the Old Howard, and while it did have a full service restaurant, its hot dog stand was the primary draw. Ed Insogna, an heir to the Joe & Nemo’s ownership, proclaimed it “one of the first fast food restaurants.” Their special hot dog formula came from the New England Provision Company (NEPCO), and the restaurant steamed the buns above the water with boiling hot dogs, before serving them with mustard, relish, onions, and horse radish. It survived beyond Scollay Square, eventually expanding to 27 other locations starting in the 1960s, but other neighborhood businesses weren’t so lucky.

The square’s businesses struggled following World War II. During the war, the constant influx of sailors allowed the theaters, hotels, taverns, and restaurants to thrive, but they couldn’t maintain that economic activity into the 1950s. Many people were moving from the cities to suburbs, and Scollay Square was turning into a red light district with a seedy reputation. By 1957, Scollay Square’s aggregate real estate value declined by a third since the great depression years, which demonstrates the power and popularity of burlesque during the 1930s. An ambitious new mayor, John Hynes, sought to revitalize this supposedly decrepit area by any means necessary.

Using federal funding from the 1949 Housing Act, the Hynes Administration, along with the recently established Boston Redevelopment Authority (BRA), formulated a plan to demolish Scollay Square and build a new neighborhood now known as Government Center. Most of the West End was razed by the late 1950s, and by 1962, Scollay Square followed suit. Although the National Register of Historic Places hadn’t yet been established, a citizen’s group tried to save the Old Howard by designating it as a national shrine and emphasizing its importance as a historical theater, but their efforts faltered after a mysterious fire set it ablaze in 1961. Other cultural landmarks, like the building that housed the influential abolitionist newspaper, The Liberator, were dismantled with the rest of Scollay Square.

In 1986, popular local radio host Jerry Williams led a campaign to change the name of Government Center back to Scollay Square, and his program featured hours of elder Bostonians calling in and sharing memories from the square. West Enders spoke of the welcoming business owners, and how children could safely roam the streets throughout the day, a stark contrast from the Combat Zone, the adult entertainment district that developed in the wake of the Scollay’s demolition. In 1987, Mayor Raymond Flynn presided over a small ceremony that “officially” restored the Scollay Square name.

But the ceremony had little impact. Bostonians refer to the area as either Government Center or City Hall Plaza, and despite establishments like Red Hat and Grotto borrowing names from old Scollay restaurants, there’s scant resemblance to the vibrancy of its heyday. Although many architectural buffs appreciate City Hall, the brutalist structure was roundly criticized upon its completion in 1968. Designers envisioned it to resemble Rome’s St. Peter’s Square, but City Hall Plaza has never been a destination like Scollay Square was, and is largely unpopular with Bostonians.

Scollay Square challenged the social norms of a more prim and proper entertainment landscape. It survived and evolved through different iterations of the city, and its untimely destruction provided impetus to preserve neighborhoods like the North End, which city planners wanted to tear down around the time. For folks who recall experiencing Scollay Square as its peak, they speak of it with a giddiness, a twinkle in their eyes. Even without physical reminders, this section of the city refuses to be lost in history.

Article by Neil Iyer, edited by Grace Clipson.

Sources: Ashland Public Library, MA, “The History of Scollay Square with Author David Kruh”; Bambino Musical, “Last Days of Scollay Square: 1940-1960”; Joan Ilacqua, “Recovering a Sordid Past: Public Memory of Scollay Square,” University of Massachusetts, Boston; David Kruh, Always Something Doing: Boston’s Infamous Scollay Square (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1989); Thomas O’Connor, Bibles, Brahmins, and Bosses: A Short History of Boston (Boston Public Library, 1991); Ryan W. Owen, “If you were to walk…Boston’s Scollay Square and Tremont Street, 1895,” Forgotten New England; Anthony M. Sammarco, The Other Red Line: Washington Street, From Scollay Square to the Combat Zone (Arcadia Publishing, 2021); The West End Museum, “Ed Insogna of Joe & Nemo’s Grill (AV0001 WEVN M 073 S073).”