The Boston-1915 Movement and the West End

The Boston-1915 Committee was formed in 1909 to improve conditions in Boston and to make it “the finest city in the world” by 1915. For many West Enders, Boston-1915 represented the promise of a brighter future, but none of them could have foreseen that some of the movement’s ideas would inspire city leaders to demolish the West End half a century later.

As the 20th century approached, many Americans knew that their large central cities were in trouble. The rapid expansion of urban industrialization that began in the 1880’s, and the accompanying flood of foreign-born immigrants and migrant workers from rural America in search of opportunity, led to overcrowded, polluted, and unhealthy urban areas. Reform movements such as City Beautiful, and individual reformers – most famously photographer Jacob Riis and social work pioneer Jane Addams – sought to bring the human cost of urbanization into the public eye and inspired projects designed to improve the physical conditions of cities and the lives of their residents.

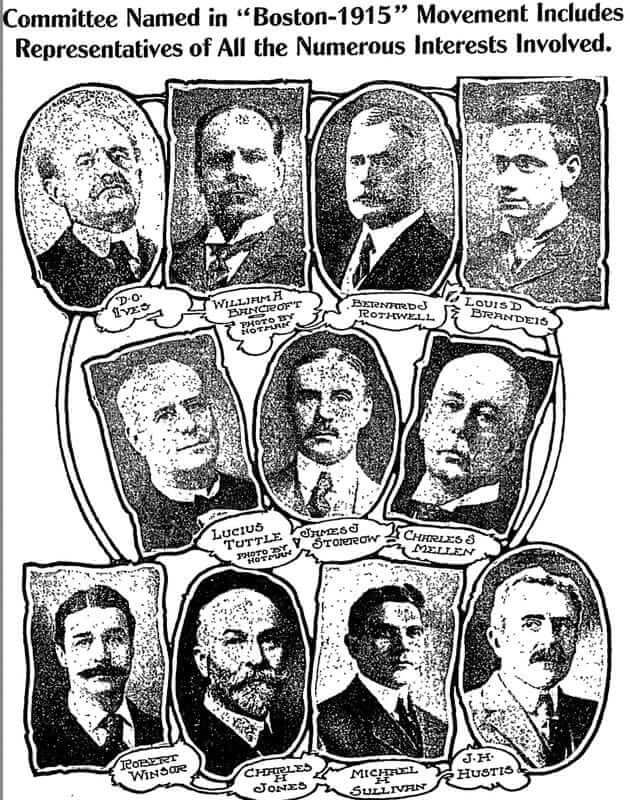

Boston’s attempt at City Beautiful was the Boston-1915 movement. The concept was first reported by the Boston Globe on March 31, 1909 and credited to Edward A. Filene, owner of one of the city’s most prominent department stores. With the support of Mayor John Fitzgerald and over 225 of Boston’s most influential leaders, including James J. Storrow (investor, politician, and main benefactor of the West End House) and Louis D. Brandeis (future U.S. Supreme Court Justice), the group quickly set out to fulfill its mandate of making Boston “the finest city in the world” by 1915. To do that meant bringing together government, business, labor, education, charitable, and religious institutions to collectively work to improve “public finances, health, industrial resources, transportation facilities, branch libraries, art, lectures, open-air concerts, etc.”

Boston-1915 fever swept the city for over two years, receiving almost daily mention in local newspapers. Committee leaders spoke to political, labor, school, and business groups throughout the metropolitan area and even into neighboring New England states. Priests, ministers, and rabbi’s praised the potential glories of the Boston-1915 programs and pressed their congregations for support. Within its first year Boston-1915 placed benches in the Boston Common for working woman, sponsored a very popular city-wide boys athletic competition (the finals at Wood Island Park attracted a crowd of 10,000), and organized an exposition which showcased the “vital activities which are at work in the community for the social, civic, educational, health and industrial betterment of the people.”

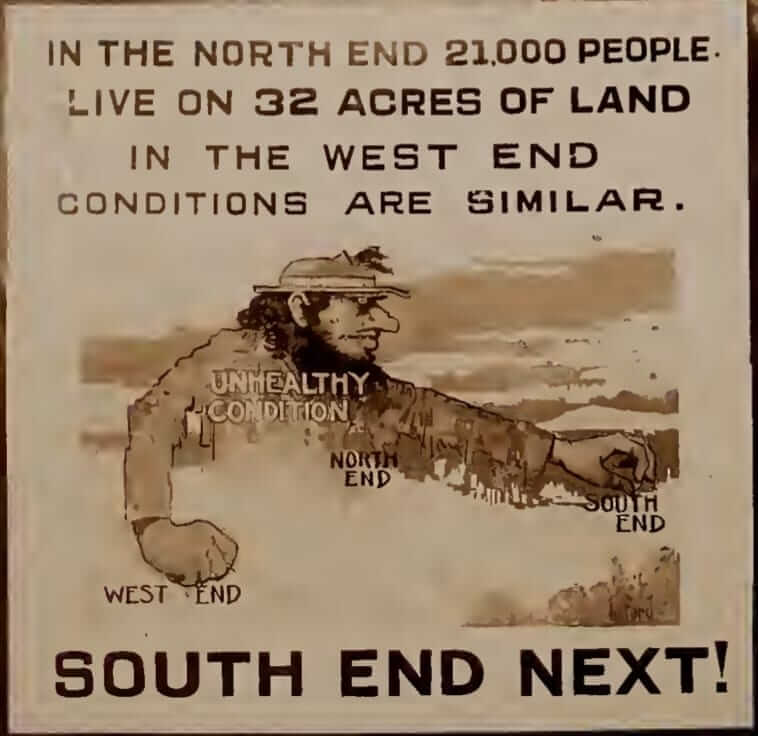

At that first exposition in 1909, institutions from the West End (West End House, Elizabeth Peabody House, Hebrew industrial School, etc.) enthusiastically participated by providing displays that demonstrated their efforts in supporting their neighborhood. Knowing that one of the West End’s greatest benefactors, James J. Storrow, was a director of the Boston-1915 Committee, would certainly have gone far in convincing these organizations, and many West End residents, that the goals of the movement (improving education, transportation, economic opportunity, and health) aligned with the desires of the neighborhood. Yet not far down the hall, the Boston-1915 Housing Committee display advertised to thousands in Boston and around the country that life in the West End and other areas of Boston was congested, unsafe, and unhealthy.

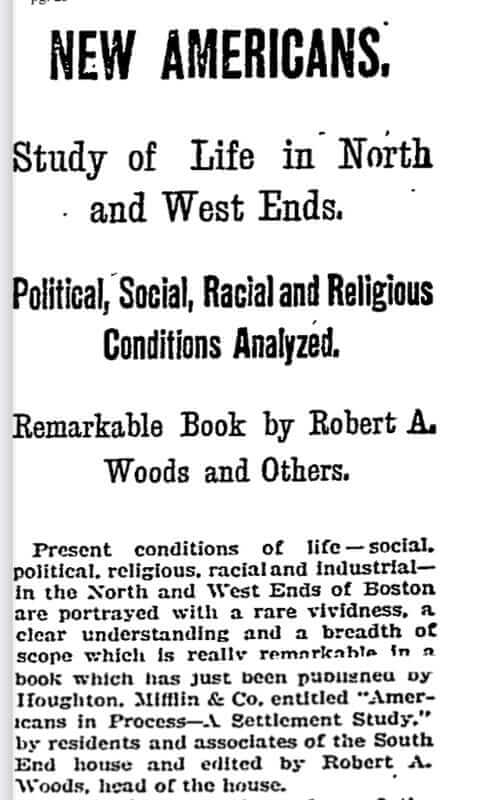

Anyone familiar with the past work of another Boston-1915 director, Robert A. Woods, founder of the South End House, would not have been surprised that this view was being expressed at the 1909 exposition. Woods was the editor of the 1902 book, “Americans in Process,” a study of the living conditions in the North End and West End. One of the book’s contributors argued that “the present condition of tenement houses in the North and West Ends is not satisfactory from any point of view” and would be a vital problem for the city “for many years to come.” Most prophetically, the Boston-1915 Housing Committee report of 1910 stated that “so far as conditions of congestion are concerned, we find this evil to be largely confined to the North and West Ends (Wards 6 and 8),” and that a “gradual moving-out process” could be the solution.

By 1912, Boston-1915 disbanded, claiming that its goals were generally met or subsumed by other private or public institutions. The movement made some short-lived, and some longer-lasting, positive contributions to the West End and the rest of the city. Much to the detriment of the West End, however, it also perpetuated the notion that tightly packed blocks, narrow streets, and a lack of recreational spaces were threats to public health and welfare. Though the leaders of Boston-1915 were focused on improving housing for the working class, and could not have predicted what the Housing Act of 1949 would create half a century later, the language and logic it proposed ultimately influenced the decision made by Boston political leaders to target the West End for urban renewal and its eventual clearance.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: “1915” Boston Exposition official catalogue and yearbook, 1909, Box: 4. Landmarks Commission reference library, 5210.008. City of Boston Archives; “BOSTON-1915 EXPOSITION OPENS TO PUBLIC TODAY: IT TELLS WHAT THE CITY …” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922); Nov 1, 1909; ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Kennedy, L. W. (1992). Planning the City upon a Hill: Boston since 1630; Lawrence W. Kennedy. University of Massachusetts Press; Krieger, A. (2019). City on a Hill: Urban idealism in America from the Puritan to the Present. The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press; O’Connor, T. H. (1993). Building a new Boston : politics and urban renewal 1950-1970.Thomas H. O’Connor. Northeastern University Press: “Report of the Housing Committee of Boston-1915, April 10, 1910, Internet Archive; “THE NEW PLAN.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Apr 02 1909, p. 10. ProQuest. Web. 25 Oct. 2022; Woods, Robert Archey. Americans in Process; a Settlement Study. / [By Residents and Associates of the South End House] Robert A. Woods, Editor. New York: Arno Press, 1970.