The Home for Aged Colored Women

The Home for Aged Colored Women was founded in the historic West End, on the north slope of Beacon Hill in 1860. The organization’s objective was to financially support and house elderly and poor Black women being turned away from existing charitable institutions. The organization raised enough funds to build an institution that served the community through the 1940s.

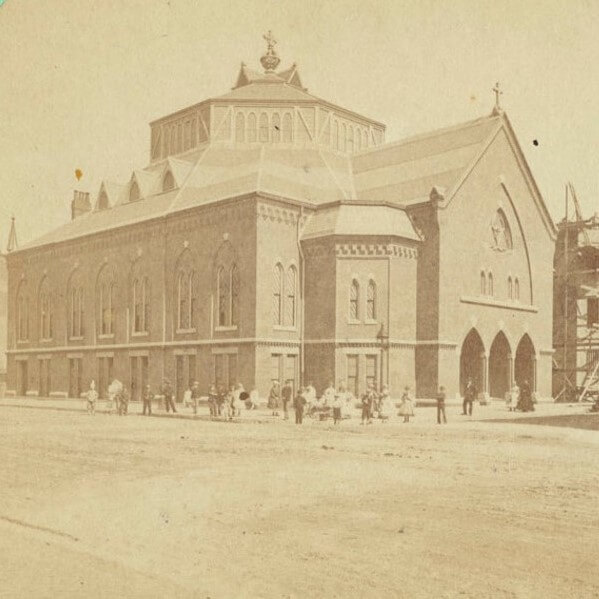

The Home for Aged Colored Women was established in January 1860 at a meeting in the office of Rev. James Freeman Clarke at the Church of the Disciples on Warren Avenue. The subject of the meeting was how to assist Boston’s elderly and poor Black women who were regularly turned away from existing charitable institutions, such as the Home for Aged Women (founded in 1850 at 36 Charles Street, near Beacon Hill). Boston’s political leaders and the upper class were typically hostile to public assistance for the poor, and private charity was reserved only for those who met the elites’ criteria for being “respectable.” Respectability often meant native-born, as wealthy Bostonians looked down upon foreign-born immigrants, then predominantly Irish, who recently arrived in Boston. But the notion of respectability was also shaped by racial bigotry towards Black Bostonians.

Poor Black women, regardless of their good standing or religious devotion, were often turned away from Boston’s public almshouses or private institutions, like the Home for Aged Women, that nominally accepted people of color. One motivation behind this exclusion was to manage the apparent prejudice of poor Whites already present at the almshouses. Anna Jackson, writing in 1900 for the annual report by the Home for Aged Colored Women, observed that during the mid-19th century, “no private institution would receive colored women, and the white paupers in the almshouses would not associate with them…” Thus, Black women’s last resort for assistance, if they could not be helped by family, often came from admittance to “insane” asylums. These exclusionary circumstances prompted Black and White community leaders to act, which led to the founding of the Home for Aged Colored Women.

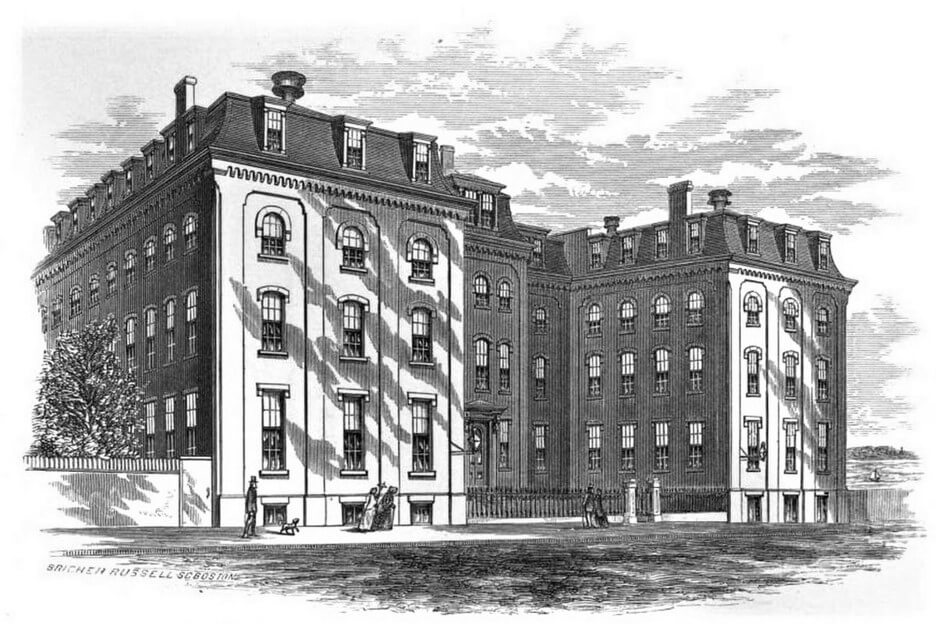

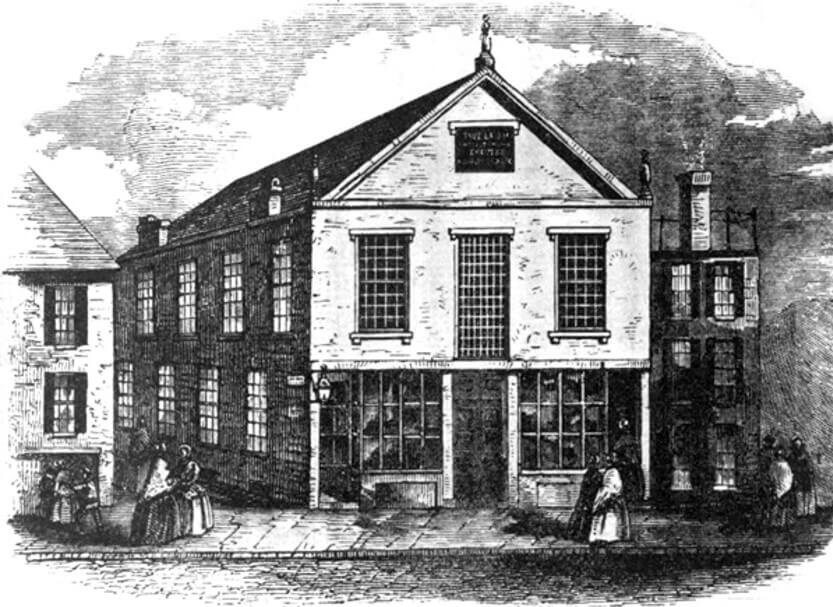

Attendees of the meeting at Rev. Clarke’s office included Rebecca Parker Clarke (his mother), Rev. Leonard A. Grimes of the Twelfth Baptist Church, then on Phillips Street, and John Andrew just before he was elected Governor of Massachusetts in 1861. They all agreed that subscriptions should be raised for the construction of a home for Black women, 60 years and older, who were unable to financially support themselves or turn to family for assistance. The first subscribers meeting was held on January 18, 1860, and soon raised the funds to rent a home at 65 Southac (Phillips) Street on the north slope of Beacon Hill, in the historic West End. Subscribers also donated furniture, and the Home for Aged Colored Women soon received applications submitted by the friends of elderly Black women on their behalf. By April 1860, ten women moved into the home on Southac Street, but by August the Home moved to a building at 27 Myrtle Street with more space and more modern accommodations. The organization would not be officially incorporated until March 4, 1864, when subscribers elected a group of officers and a Board of Directors.

The Home for Aged Colored Women redressed the racial exclusion associated with “respectability” but did not abandon the concept entirely: only “respectable” Black women were admitted into the home. Residents (called “inmates”) had to participate in morning prayer and housework and lived under the supervision of a matron. The elderly Black women were “expected to knit and sew,” but would “not be allowed to sell any article, or to work out of the house,” according to the Home’s official rules. In the name of respectability, all of the Home’s “inmates” were subject to a three-month probationary period, after which they could stay under the Home’s care if they followed all of its rules.

While residents were generally prohibited from selling the items that they sewed, Matron Rachel Smith bent this rule when she secured approval in 1875 for the women to participate in a fair to sell their wares from inside the Home to visitors. The fair grossed $327 in its first year to support the Home, and each resident was given fifty cents as a thank-you gift. This fair subsequently became an annual tradition which the residents enjoyed.

The Home for Aged Colored Women, which never had more than nineteen residents at its peak in 1915, also assisted non-resident elderly women by providing them with a monthly supplemental income (varying from $2 to $12) to help them to live independently or to defray the cost to supporting families. In 1915, fifty-eight elderly Black women were receiving this kind of assistance from the Home for Aged Colored Women.

The Home for Aged Colored Women remained at 27 Myrtle Street until 1900, when it moved to 22 Hancock Street, where Charles Sumner’s house once stood. The move to Hancock Street was prompted by “the evolving needs for the Home, particularly with regard to space, structural safety, and modern sanitation” according to the Massachusetts Historical Society. In 1944, the Home for Aged Colored Women ceased its operations after a significant decline in the number of residents. The Board of Directors continued its monthly financial aid until 1949, when the Home published its last annual report. The Home for Aged Colored Women reflected the longstanding tradition of mutual aid in Boston’s Black communities, as well as the initiative shown by Boston’s Black churches and White allies to address racial disparities in poor relief during the 19th century.

Article by Adam Tomasi, edited by Bob Potenza

Sources: Massachusetts Historical Society; National Park Service; The Grimes-King Foundation for the Elderly, Inc.; Esther MacCarthy, “The Home for Aged Colored Women, 1861-1944,” Historical Journal of Massachusetts 21:1, Winter 1993; Black Bostonians by James Oliver Horton and Lois E. Horton (Internet Archive)