The Origins of the Boston Garden

The story of the fabled Boston Garden is nearly as winding as the 10 tracks that snake from beneath its modern-day successor on Causeway Street. The intersection of frontier entrepreneurship and New England business interests, the arena came to represent the crosswinds of the rapidly changing American public and the economic forces that shaped it during the Roaring Twenties.

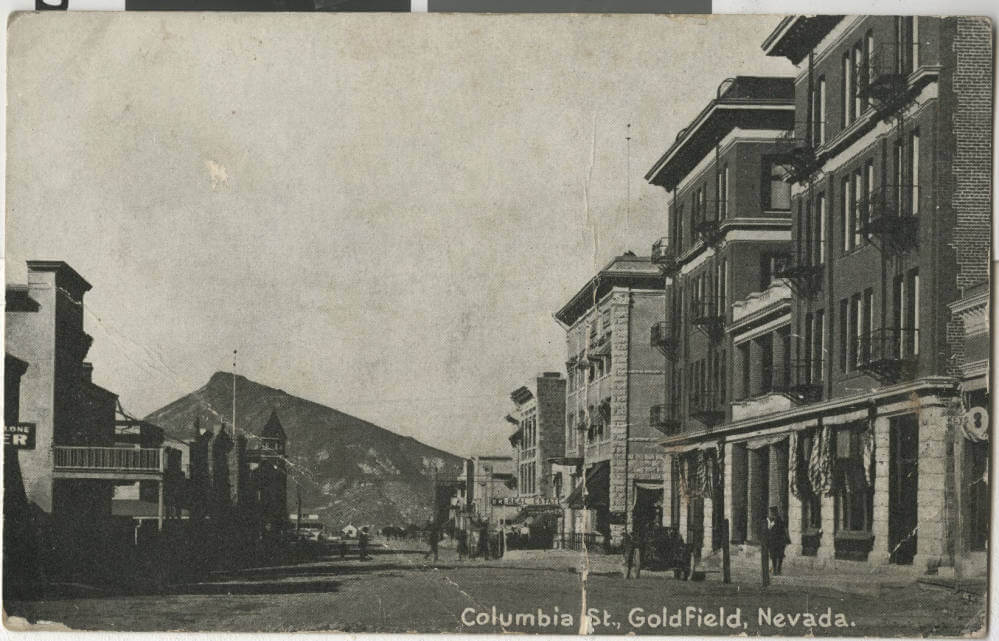

America was primed for a sports explosion in the 1920s as disposable income and leisure time soared, radio adoption became widespread, and the advent of the automobile allowed spectators to travel from further than ever before. Few men led the charge as effectively as George “Tex” Rickard, equal parts opportunist and trailblazer, in capitalizing on these growing trends and pioneering American sports popularity. With a square jaw, deep-set eyes, and pursed lips, Rickard amassed his fortune first as a gambler in the Canadian Yukon before traveling 3,000 miles south to Goldfield, Nevada where he opened a casino in the mining town and turned his sights to boxing.

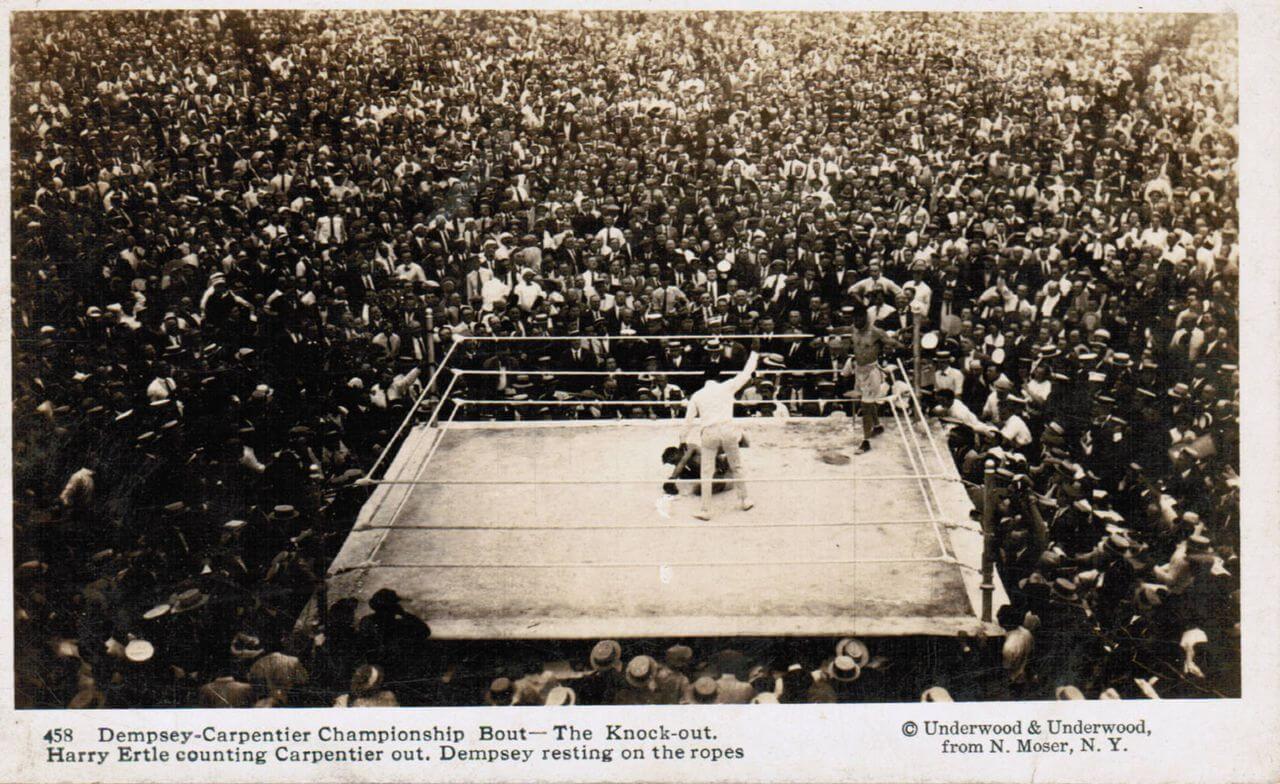

After Rickard promoted “The Fight of The Century” there in September 1906 between Joe Gans and Oscar Nelson, he realized a well-marketed, highly organized boxing match could prove extremely lucrative. Tex Rickard relocated to New York in 1920 when new legislation legalized boxing in the state, poised to command the attention of population centers in the northeast with his heavyweight spectacles and the help of the financial backing he earned in Nevada.

On June 27, 1835, four decades before Rickard’s birth in Missouri, the Boston & Maine (B&M) Railroad was chartered in Massachusetts. Through a series of acquisitions, mergers, and leasing agreements in the latter half of the 19th century B&M consolidated 47 regional railroads, most of which had sprung up after the Civil War to link rural manufacturing towns to shipping hubs in Boston, New York, and Montreal. The railroad became the primary operator in the Northeast, controlling over 2,300 miles of track and employing 28,000 people.

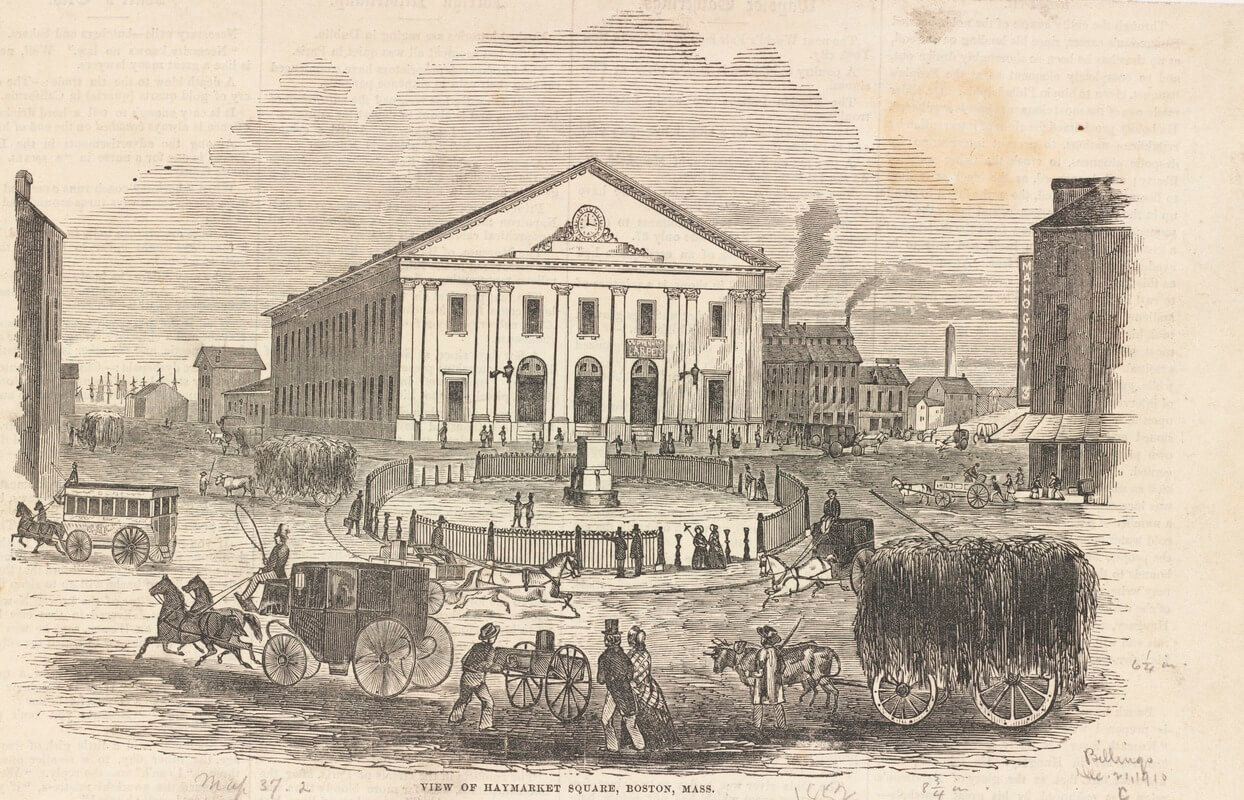

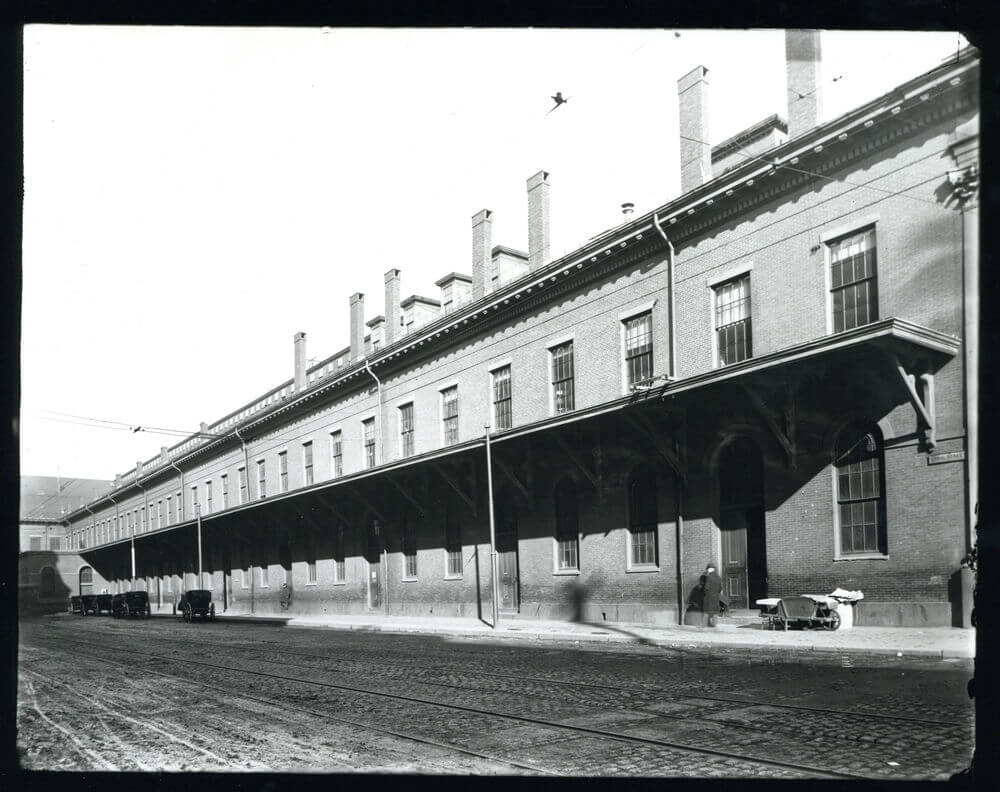

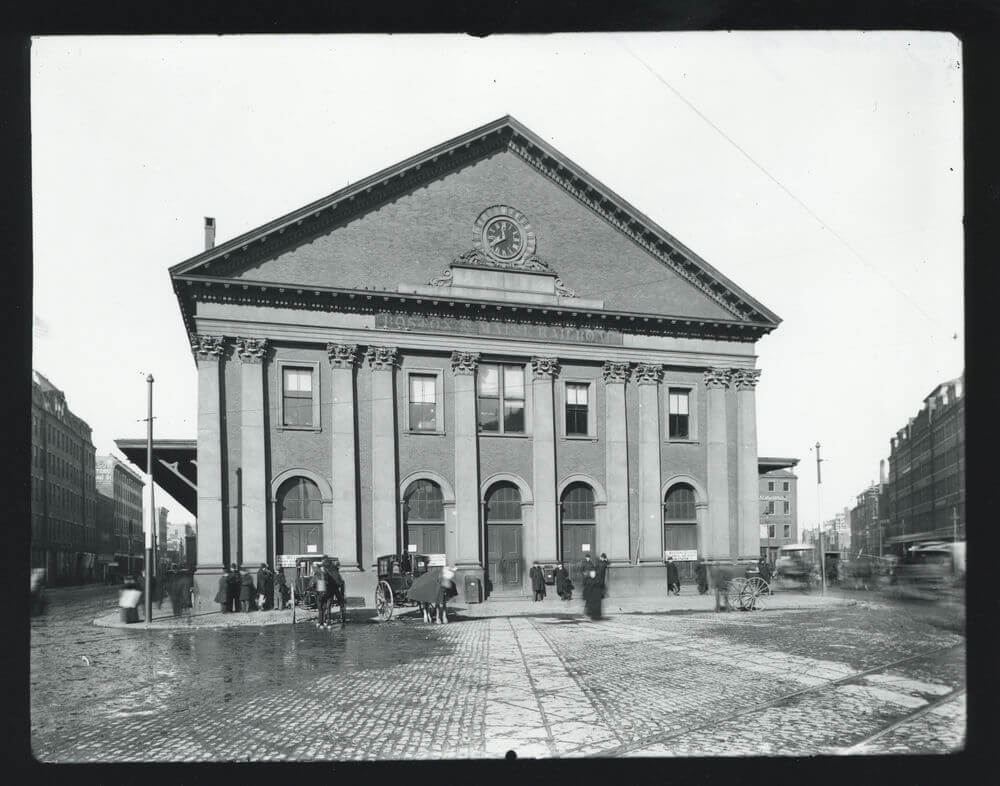

B&M was one of several railroad companies to construct a rail depot in Bulfinch Triangle prior to 1880. Unlike its contemporaries, which had stations on Causeway, the Boston & Maine’s tracks extended into the city along Canal Street to Haymarket Square, on the former site of the Middlesex Canal.

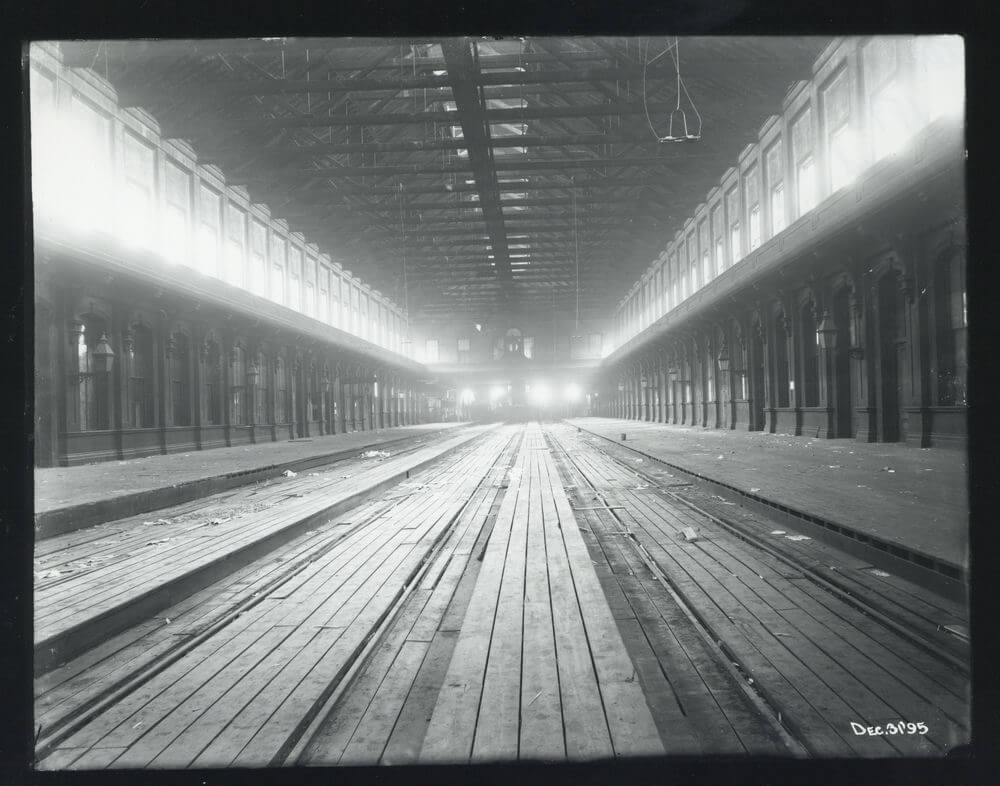

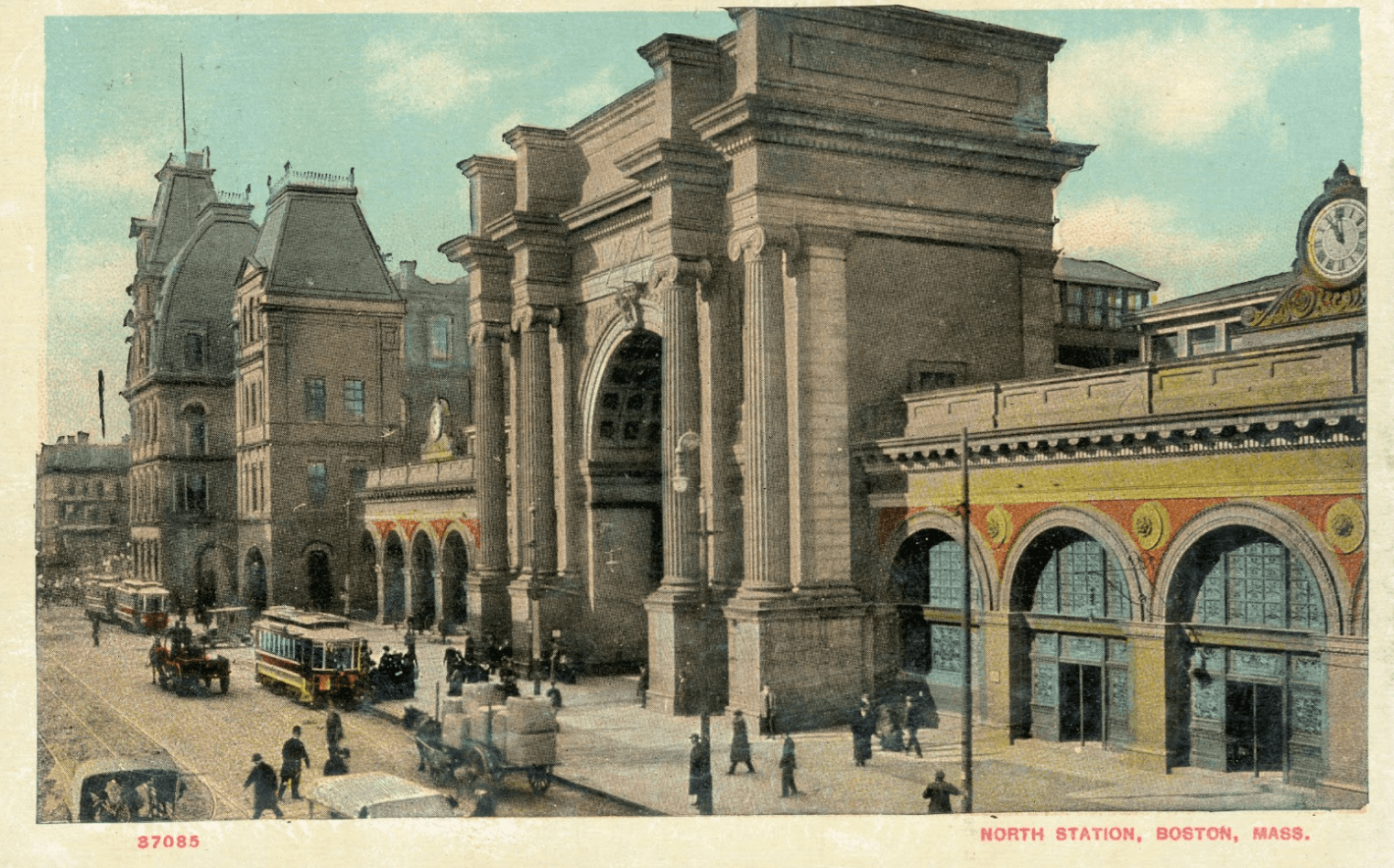

By 1893, B&M controlled the rails leading to the Eastern & Lowell stations on Causeway Street through leasing agreements allowing the construction of Union Station, a towering neoclassical-style building bringing the Eastern, Lowell, and B&M Stations under one roof. The former station was demolished in 1897 and replaced by the northern terminal of the Tremont Street Subway, which opened the following year providing above-ground access to the country’s oldest subway system. Meanwhile, just up the street over 30 million passengers each year passed through the new Union Station’s doors. By the 1920’s, B&M Railroad was prepared to construct an even grander station – this time around, with an unexpected business partner.

After moving to New York Rickard quickly became a household name with the help of the era’s top fighter, Jack Dempsey. In 1925, Tex Rickard financed the construction of the third iteration of Madison Square Garden located at 8th Ave and W 50th Street in Manhattan for $4.75 million. Through his Madison Square Garden Corporation, Rickard and his business partners sought to replicate the success of the Garden in cities across America, many of which lacked modern arenas – if any at all. With seven stadiums planned in total, Boston interested Rickard as a potential opportunity.

The only venue comparable to the Garden in Boston at the time was the Boston Arena. Built in Fenway in 1910 and famed as the oldest indoor ice hockey rink in the world, the arena seated roughly 5,000 spectators and hosted small boxing events and early Bruins games. However, in an era where Rickard and Dempsey’s title boxing matches were drawing crowds of 80,000, the financial incentive for greater seating capacity could not be understated. Rickard eventually partnered with B&M Railroad, whose president Homer Loring announced their planned stadium would “attract the largest conventions because it will be able to provide adequate seating capacity now almost entirely lacking… [in Boston, and would provide] a sport arena large enough to accommodate major attractions.”

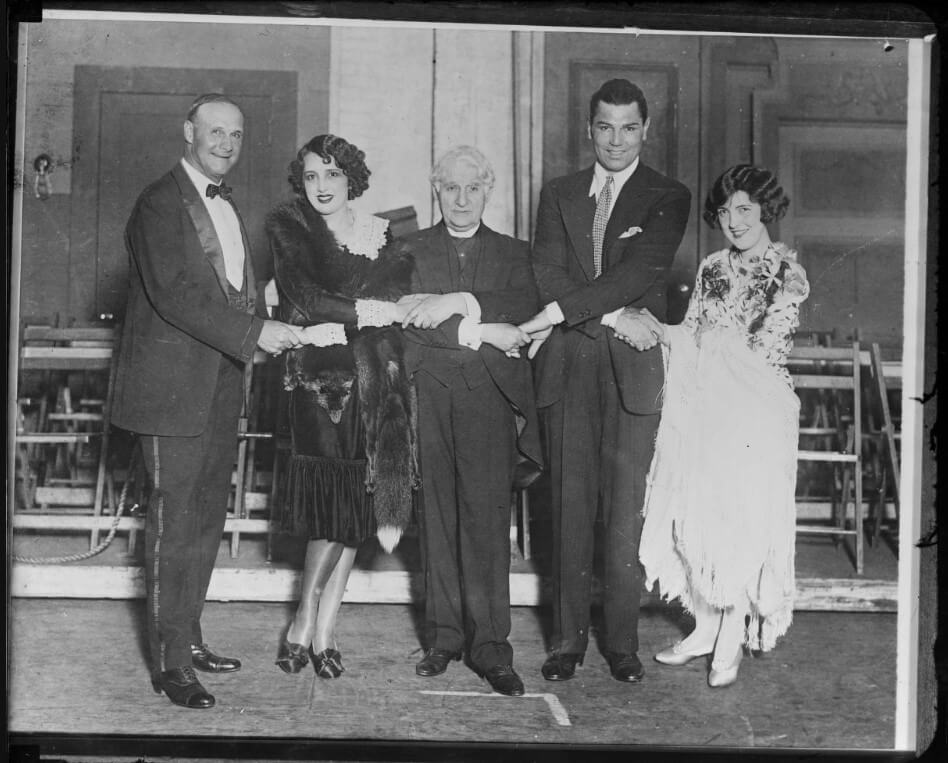

Loring presided over B&M when overdue plans to replace Union Station came to fruition. The new North Station on Causeway Street initially included a new rail terminal, corporate headquarters, and offices. As designs formulated, Boston real estate developer James Walsh realized the potential of adding a stadium atop the station, “instantly accessible to persons getting off Boston & Maine trains”. Walsh enlisted prominent Boston Architect George C. Funk, a designer of the Boston Arena, to draft station plans with a hotel and arena included to present to B&M. In the same breath, Walsh had contacted Rickard to gauge interest in his vision. Rickard, who was eyeing Boston as a location for a second Madison Square Garden, was receptive to the idea and visited Boston in November of 1927. Five days later, B&M and Rickard announced a joint venture where the railroad would construct an 18,500-seat sports arena to lease to the Madison Square Garden Corporation.

The first-of-its-kind venture faced resistance from B&M shareholder Edmund D. Codman, who contested the partnership violated the corporation’s charter since the arena was a non-railroad building. Legal proceedings eventually prevailed in favor of Rickard when the Massachusetts General Court officially expanded the corporate powers of the railroad in March of 1928 to permit the stadium’s construction, and allowed the adjoining Hotel Manger to be built in 1929 for its August 30, 1930 grand opening.

Only eight months after the court ruling, a Saturday night boxing crowd cheered on Bostonite “Honey Boy” Dick Finnegan on November 17, 1928, the arena’s opening night. The Bruins played their inaugural hockey game in the Boston Garden just three days later. Rickard designed the stadium with the spectator in mind, wanting every seat close enough to see “sweat on the boxers’ brows”. The unique viewing experience for fans became a staple in the arena, which became well known for the home field advantage afforded to any Boston team.

The Boston Garden immediately became a beloved fixture of the West End, home to 16 NBA championships, 5 Stanley Cups, renowned concerts, and even John F. Kennedy’s final address to Boston during his 1960 presidential campaign. Although the redevelopment of the B&M’s original North Station complex into the modern North Station and TD Garden removed the present-day complex from its original roots, Rickard’s vision – a vibrant arena full of impassioned spectators from far and wide – still rings as true today just as it did nearly a century ago when the Old Garden first opened its doors.

Article by Meyer Aviles, edited by Adam Tomasi and Sebastian Belfanti