The Parkman Market

Charles Bulfinch and his architecture transformed Boston during the Federalist era. Many of his works, such as the Massachusetts State House, still grace the city today. One of his now lost and lesser known buildings, the Parkman Market, served the West End as a public market, a factory, and an early home of St. Joseph’s congregation. Despite its historic significance, it did not survive Urban Renewal.

During his tenure as the lead selectman of the Town of Boston, architect Charles Bulfinch had more on his mind than building his vision of a grander metropolis. There were very practical matters facing him, not the least of which was “maintaining clean and orderly streets in the town.” For decades, Faneuil Hall had served as Boston’s main market place, but owners had not expanded it to meet the needs of the town’s growing population. Without more locations from which vendors could sell their wares, unlicensed markets, carts, and throngs of customers would only worsen the existing congestion in Boston’s narrow streets. For this reason, Bulfinch authorized and planned two new markets, and as was often the case in this era, a wealthy private citizen financed the project.

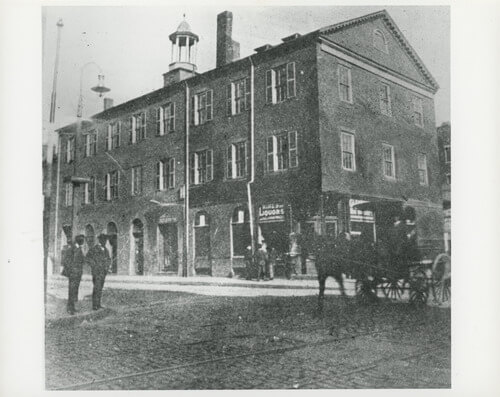

Samuel Parkman, a prominent businessman and neighbor of the Bulfinch family in the West End’s Bowdoin Square, offered to pay for one of the new markets in this growing section of Boston. The Parkman Market and the second of Bulfinch’s planned markets, Boylston Hall, both opened in 1810. The Parkman Market was described as “a large brick building at the corner of Grove and Cambridge-streets.” Its most striking feature was the “cupola which surmounts the roof, a quaintly designed affair, which cannot fail to attract the attention of the passerby who, has had a good look at it.” Considering its similarities with Faneuil Hall, some speculate that Bulfinch, loaded down with his selectman duties, may have hastily copied his own plans for the older market. Parkman and his heirs, including his son George, the ill-fated murder victim of Professor John Webster, continued to own the market building for over 100 years.

The need for a dedicated market in the West End quickly diminished after the formal organization of the pushcart market in Haymarket Square (1821) and the opening of Quincy Market (1826). As a result, the Parkman Market evolved into a manufacturing center and home to some of the most famous organ and piano makers of the day. In 1831, Elias and George Hook moved their organ-making business, E. and G. G. Hook, to the Parkman Market. After taking on an employee, Francis Hastings, as a partner, the firm became commonly known as Hook & Hastings. Hook & Hastings grew from a local to a nationally known company, and their organs could be found in schools and churches across the country. (A Hook & Hastings organ is still used in St. Joseph’s Church today.) For a short time, Plaisted & Hutchings’ organs, founded by former employees of Hook & Hastings, also took up residence in the Parkman Market. This firm went through a number of name changes during its lifetime, ultimately becoming Geo. S. Hutchings Company of Boston.

Perhaps the market’s most interesting occupant was a Catholic congregation which would one day become St. Joseph’s Parish of the West End. Needing a larger space to accommodate its growing membership, in 1854 the leaders of the congregation rented the first floor of the Parkman Market building (then known as the Old Organ Factory). Within a year the congregation required even more space and signed a ten-year lease for the entire building. The first floor became the “Chapel of the Guardian Angel,” and the second was used as a Sunday school. For eight years the Old Parkman Market served as a vessel of the Catholic Church until the Archdiocese’s purchase of the The Twelfth Congregational Society’s church on Chambers Street in 1862. This would become St. Joseph’s Parish, which still serves the neighborhood today.

For the 60 years following the departure of St. Joseph’s congregation, the Parkman Market operated as “a paint and blacksmith shop, a grain warehouse, and even a tenement house.” In 1916, George A. Parkman, son of Doctor George Parkman, donated the building to the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) which had plans to expand its campus along Cambridge and Grove Streets. At one point the building was used as a dormitory for MGH nurses.

In 1924, the City of Boston decided to widen Cambridge Street to accommodate the growth of automobile traffic. This required that many buildings, such as the Parkman Market and the Otis House (its Bulfinch cousin down the road), had to be moved or altered. While the Otis House was moved back from the street in its entirety, the Parkman Market would have forty feet of its structure removed. Unlike the Otis House, the Parkman Market would not survive the demolition of the West End. In 1960 the building was razed to the ground. Today the MGH’s Paul S. Russell Museum occupies the former site of Bulfinch’s Faneuil Hall of the West End.

Article by Bob Potenza, edited by Sebastian Belfanti

Sources: Snow, Caleb H., A History of Boston: The Metropolitan of Massachusetts. Abel Boswen, Boston, 1828.; Kirker and Kirker, Bulfinch’s Boston, 1787-1817.Oxford University Press, New York, 1964.; “WEST END RELIC OF BULFINCH.: PARKMAN’S MARKET, ON CAMBRIDGE AND NORTH GROVE STS, HAD HAD 95 YEARS OF UNINTERRUPTED RENTALS.” Boston Daily Globe (1872-1922), Aug 07 1905, p. 11. ProQuest. Web. 26 Dec. 2023.; St. Joseph’s Church, 125 Anniversary, Golden Book of Memories.; organhistoricalsociety.; org;pipeorgandatabase.org.